Often described as part cookie and part cake, Tea Cakes are a southern favorite. This version of the recipe dates back to Tallahassee during Florida’s early years of statehood. The author of it is Mary Simpson Brown Archer. Mary kept recipes, cleaning tips, and more in a notebook that today provides us and historians with a small window into the daily life of Tallahasseans from the Antebellum to the Reconstruction eras. What follows is not only the tasty recipe of what has been called “THE Florida Tea Cake,” but also explores more about the woman who wrote down this special recipe.

Who was Mary Simpson Brown Archer?

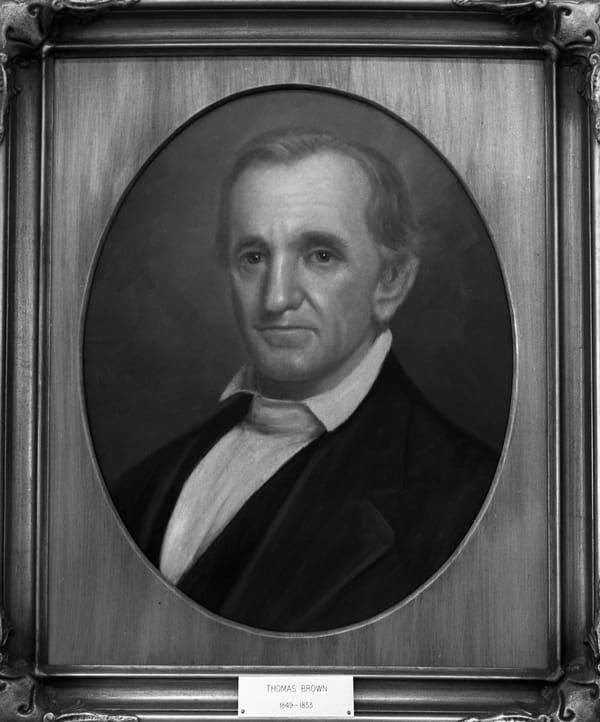

Mary Simpson Brown Archer was born in Virginia on December 21, 1821. Her parents, Thomas and Elizabeth Brown, moved their family and 140 enslaved people to Florida Territory when Mary was around seven years old. One of seven children, Mary grew up in Tallahassee where her father built a large hotel called Brown’s Inn. In 1849, Thomas Brown was elected the second governor of the new state of Florida. By then, Mary was 27 and married to James Tillinghast Archer. Archer was the first Secretary of State in Florida and later served as Florida’s Attorney General.

The couple had two children: Thomas in 1849 and Susan in 1850. Mary’s husband James died just a few years later in 1859 at the age of 40. The family strongly supported the Confederacy before, during, and after the Civil War. In addition to her father and husband owning enslaved people, Mary’s son was one of the West Florida Seminar cadets who fought for the Confederacy at the Battle of Natural Bridge south of Tallahassee in 1865. Furthermore, at the request of her brother-in-law, Mary hid all of Florida’s Confederate Battle Flags at the war’s end so they would not fall into the hands of the Union Troops occupying Tallahassee. Mary kept them a secret and protected them until the end of Reconstruction when she returned them to the state.

Mary described in a letter to her sister about the economic hardships the city and her family had fallen upon after the war. However, the family must have still owned her father’s Inn. After his death, Mary took over the operation of it in 1870. She ran it under the name “The City Hotel” for four more years before it passed out of the family. Mary died in 1894 and is buried at Tallahassee’s Old City Cemetery near her husband.

While there are paintings of both her father and husband in the Archives of the State of Florida and a photo of her father and one of her sisters, there is no painting or photo of Mary.

Mary Archer’s Recipe Notebook

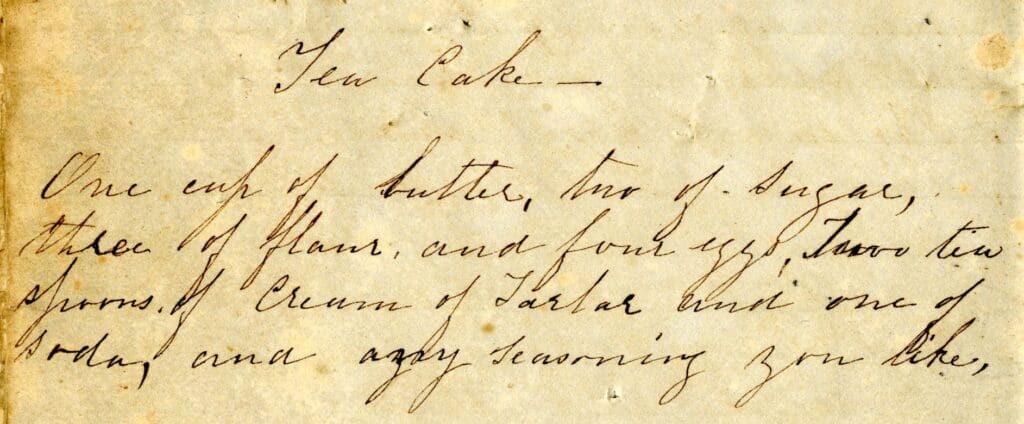

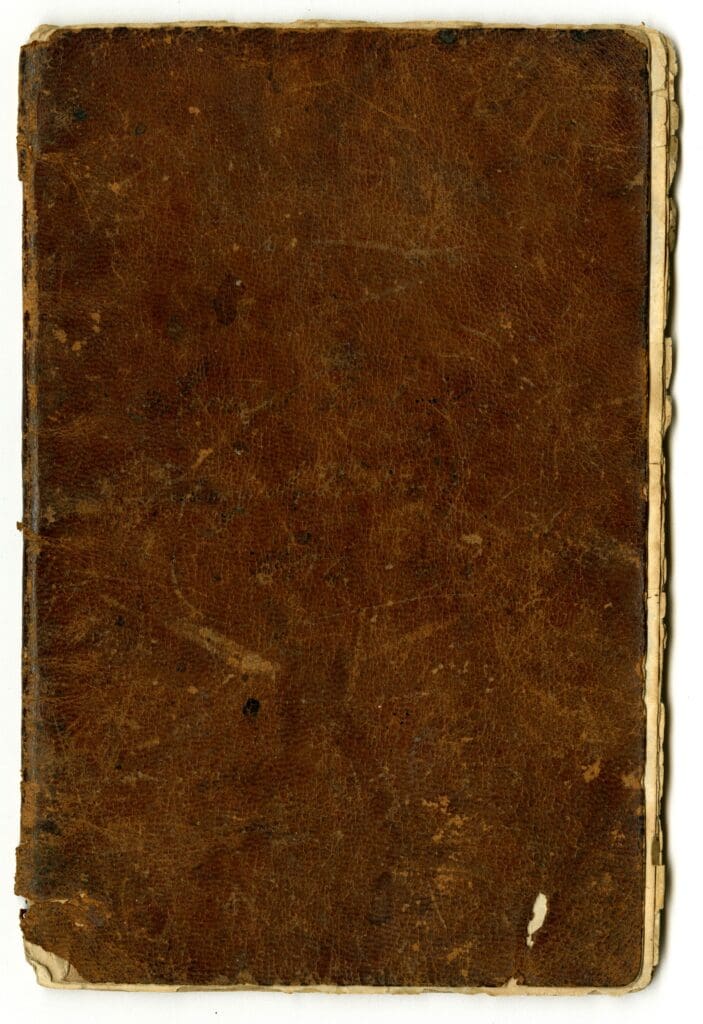

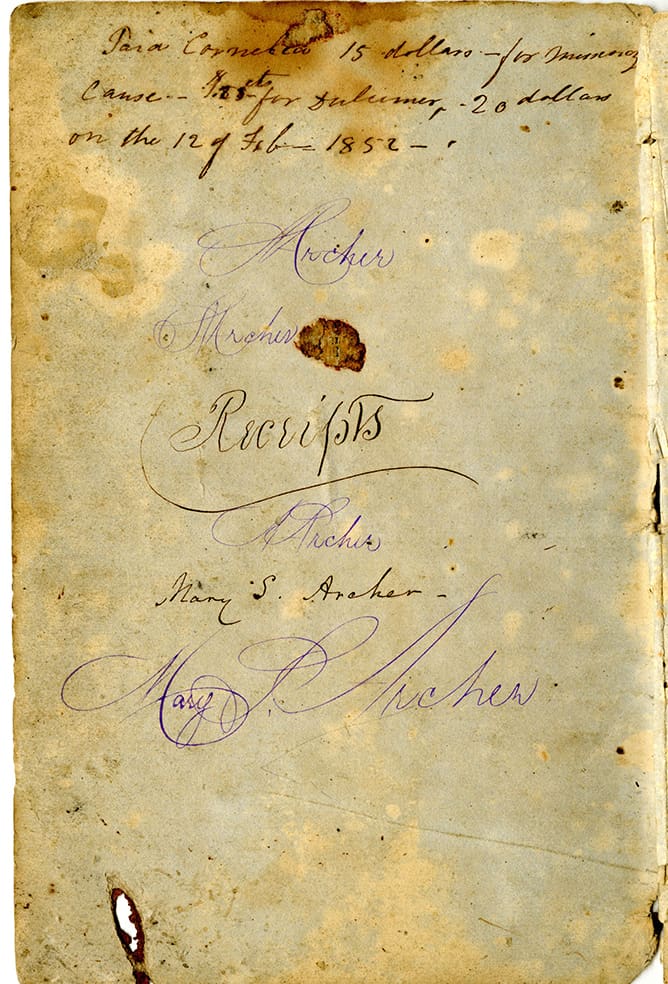

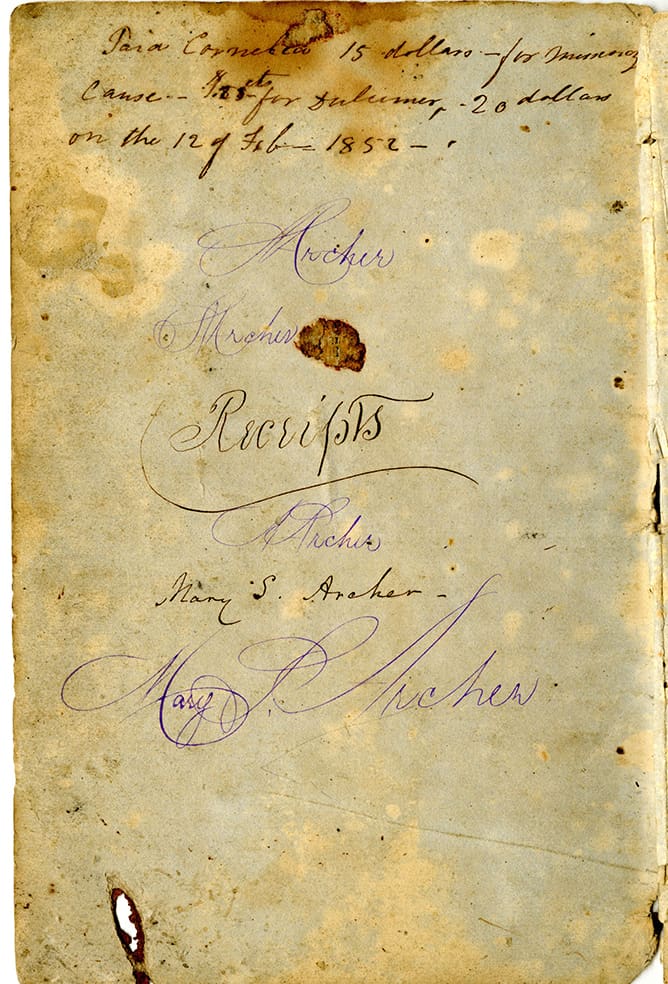

Mary’s son and his wife died young with no children. Meanwhile, Mary’s daughter lived to be 82, but never married. At some point, Mary Simpson Brown Archer’s notebook with the handwritten recipes was donated to the State Library and Archives of Florida. The entire notebook is online, and you can read it for yourself. At two points in the book, dates are mentioned. The first is “1852,” when Mary wrote her name multiple times in the front of the book. The other is “1869”, when Mary’s 20-year-old son practiced his penmanship. Those are the only clues to when the notebook with the plain brown cover was written.

Over the years, Mary recorded a variety of things beyond food recipes in the book. She included methods to remove stains (iron stains from marble), steps to cure illnesses (whooping cough), and sayings she wanted to remember (“A still tongue makes a wise head.”) Mary might not have intended some of the entries to be humorous, but when you have a recipe for “Cake” followed immediately by an entry titled “How to Destroy Flies,” you begin to wonder what happened to that cake!

Lost in Translation (and Technology!)

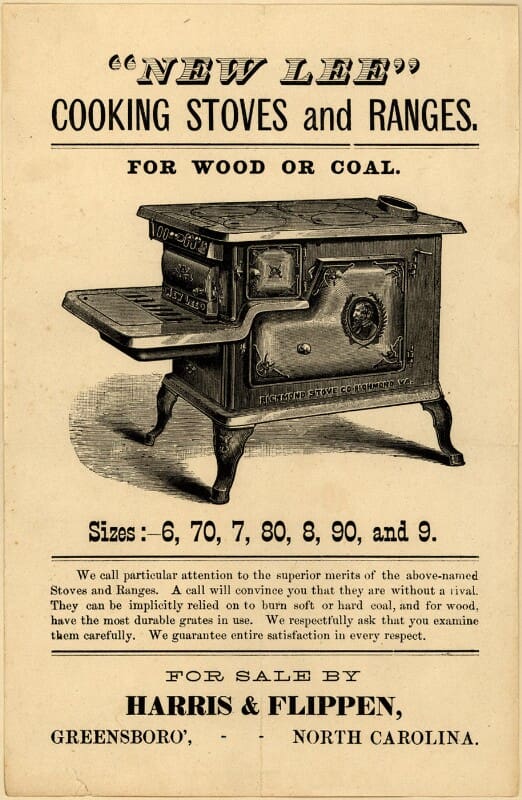

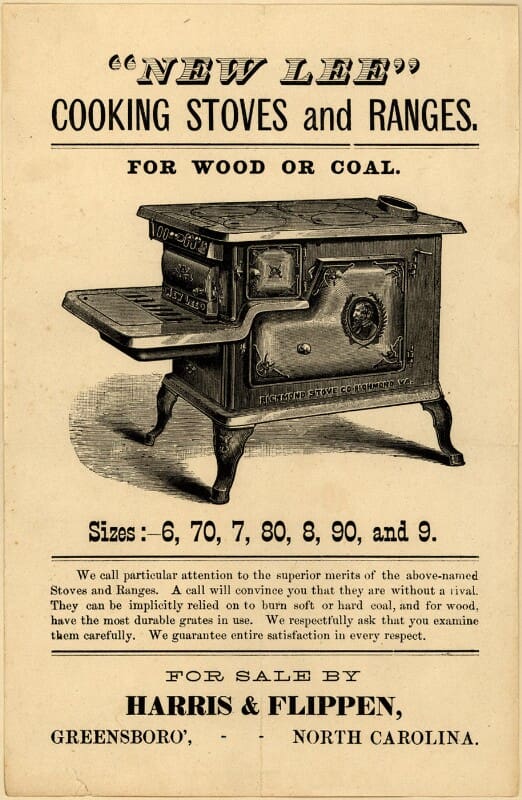

Some interesting challenges come up when you’re dealing with an original recipe that is around 172 years old. First and foremost, how do you translate cooking and baking instructions to modern technology? Sure, there were stoves and ovens in the mid-1800s, but a wood- or coal-heated oven does not exactly have the same type of capability as a modern electric or gas oven that will efficiently preheat to exactly 350 degrees. In some older recipes I’ve run across while researching for this project, I’ve seen phrases like “slow oven” and “fast oven” which I take to mean “low temperature” and “high temperature.”

In families that have passed down recipes like this, they are often modified over the generations to deal with the changing technology. Sometimes, they are rewritten, and sometimes there are just notes in the margins. Since this recipe was first written by Mary in the mid 1800s, there have been no changes or additions that would help me determine how to set the time and temperature using a modern stove. However, I did have an advantage. I knew someone who had not only makes Mary Archer’s recipe regularly but does so with with rave reviews: Beth McGrotha, who is part of the Tallahassee Historical Society and an excellent baker. Beth pointed me in the right direction regarding how long and at what temperature to bake this recipe. Thank you, Beth!

One other challenge with this recipe and others in Mary Archer’s notebook is that she didn’t always write down the preparation instructions. Sometimes, as in the case of these tea cakes, it was just a list of ingredients. Fortunately, there are many tea cake recipes out there and, while the ingredients might vary, the instructions to create these types of cookies are often similar.

If at first you don’t succeed… embrace the 1850s

In my first attempt at making Mary Archer’s Tea Cakes, I had a humorous and ironic situation happen. Just a few minutes after putting the first cookie sheet into the oven, the power in my house and my whole neighborhood went out, most likely from a blown transformer at a nearby substation. Of course, the heat remaining in the oven would continue to bake the cookies, but since I wasn’t sure how fast the oven would cool, the timer I was using was worthless. So there I was, trying to bake cookies without power using a recipe originally written to bake cookies without power. Since it was nighttime and my house was dark, I sat there shining the flashlight from my phone through my oven window trying to see/guess when the edges of the tea cake turned golden brown. I did NOT do a good job so my first tea cakes ended up way undercooked. Still, if I had thought of it at the time, I would have lit a candle instead of using my flashlight app just to get the full 1850’s baking experience.

Mary Archer’s Tea Cake Recipe

Ingredients

1 cup butter

2 cups sugar

3 cups flour

4 eggs

2 teaspoons Cream of Tartar

1 teaspoon Baking Soda

Any seasoning you like to top it. (I did some without and others with mixtures of Cinnamon/Sugar and Nutmeg/Sugar)

Preparation

- Let butter warm to room temperature.

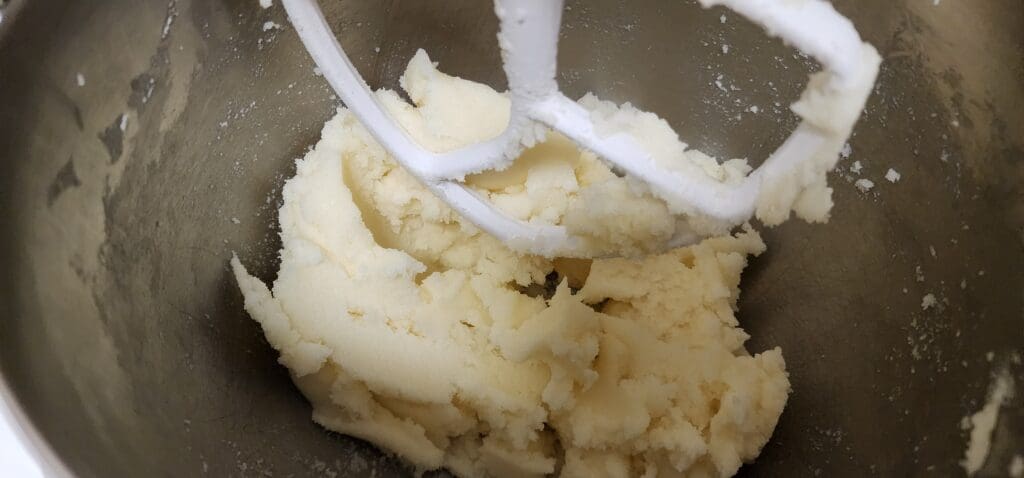

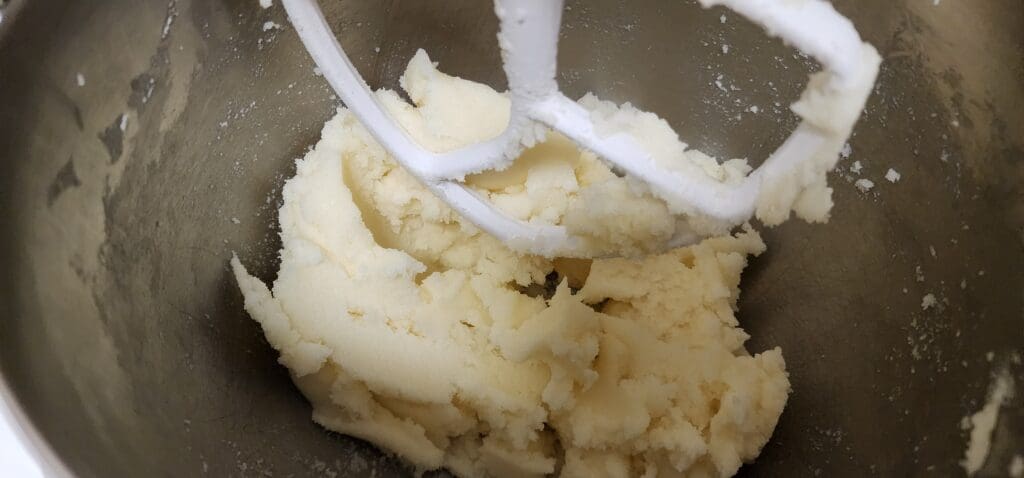

- Cream butter and sugar together until light and fluffy. Embrace technology and use a stand or hand mixer. It will take about 2 minutes or so.

- Add one egg at a time to the butter and sugar. Mix in each one completely before adding another.

- In a separate bowl, whisk your flour, Cream of Tartar, and baking soda together.

- Add about a third of the combined dry ingredients to the wet and mix. Repeat with another third. With the final third, make sure you do not overmix.

- You should have a sticky dough (very sticky if you overmix it). Depending on how you like your tea cakes (crispy or soft) will depend on what you do next. Consider this next part a “choose your own adventure” in baking!

Crispier Tea Cake Preparation

- Divide dough into manageable sections. Then wrap up each section in plastic wrap. Flatten the plastic wrap-covered dough into thick rectangles and put in the fridge for about 15 to 30 minutes.

- Place one of the chilled dough rectangles on a flour-covered area and sprinkle flour on top. Leave the others in the fridge until you are ready for it because as it warms up it will become harder to handle. Flour a rolling pin and roll out the dough until it’s about ¼ inch thick. Make sure the dough is as even as possible.

- You can use a round cookie cutter to cut out the tea cakes in the traditional style. I used a 2-inch round cutter. Beth McGrotha has also done them with an adorable Florida cookie cutter that turned out great! She calls them “THE Florida Tea Cakes”.

- Arrange the cutouts on an ungreased cookie sheet.

- Per Mary Archer’s ingredients, you can bake the tea cakes plain or sprinkle them with the seasoning of your choice. In addition to the plain tea cakes, I have also baked them using cinnamon/sugar on top and others using nutmeg/sugar. All are delicious!

- Bake at 350 degrees for 10-12 minutes until the edges are golden brown. (The bigger and thicker the cookie, the longer it will take. Keep a close eye on it.)

- Remove from cookie sheet and place on a rack to cool.

Softer and Fluffier Tea Cake preparation

- You can chill covered dough for 15 or 30 minutes to make it more firm and less sticky, but it’s not necessary. Coat your hands with a bit of flour and make little balls of dough.

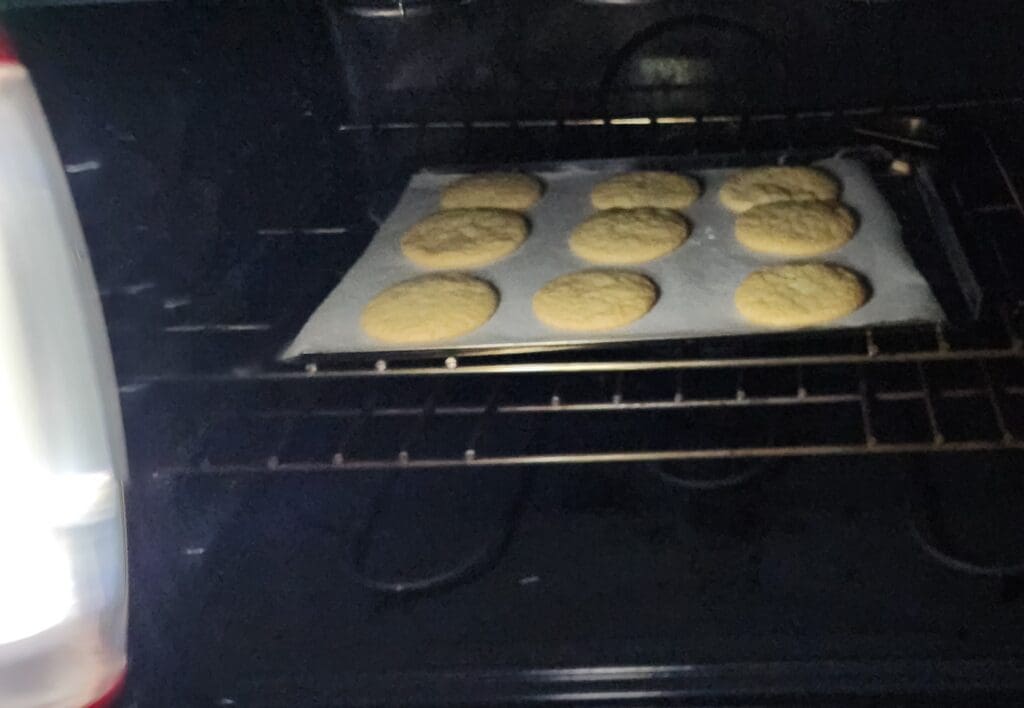

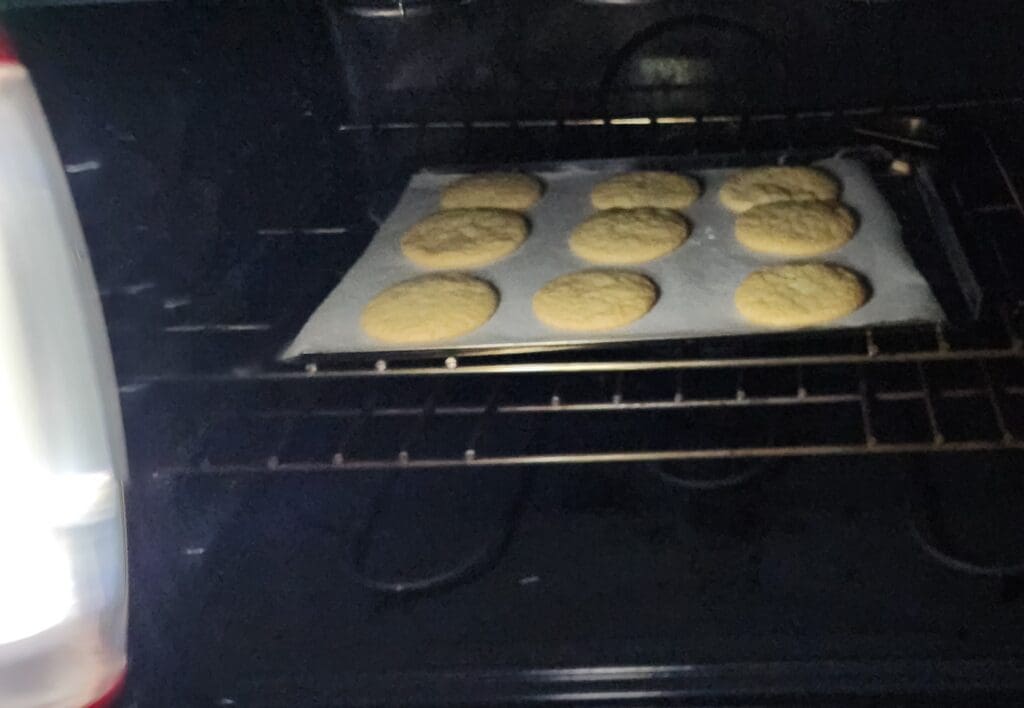

- Place the balls of dough on a parchment-covered cookie sheet. These will spread so don’t put them too close together. You can leave them round or slightly flatten them. These will be thicker than the crispier version.

- Sprinkle with the seasoning of your choice. (The plain version is tasty too!)

- Bake at 350 degrees for 10-16 minutes until the edges are golden brown. Again, a bigger or really thick tea cake may take more time. These cookies will be higher in the middle and have a softer cake-like texture in the center.

- Remove from cookie sheet and place on a rack to cool.

ENJOY!

There are a lot of other Tea Cake recipes out there. Some call for milk and others call for vanilla. What version of the recipe has been handed down through your family? Let us know at localroutes@wfsu.org.

The Roots of Local Routes Recipes

As Tallahassee celebrates 200 years since its creation in 2024, we decided to take this opportunity to dive into some of the early recipes from the Tallahassee/North Florida area. Over this next year, we’re going to be stirring up some recipes used during the Territorial period and early statehood of Florida, cook up some first foods of Native Americans who lived in this region, and try our hand at recipes that have been handed down through the generations of families who have helped settle and grow our community. With each one, we plan to share some of the local history surrounding the people who created and handed down the recipes over the decades and sometimes centuries. If you have some from your own family that you’d like us to try and are willing to share with our Local Routes audience, please send them to localroutes@wfsu.org.

Suzanne Smith is Executive Producer for Television at WFSU Public Media. She oversees the production of local programs at WFSU, is host of WFSU Local Routes, and a regular content contributor.

Suzanne’s love for PBS began early with programs like Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and continues to this day. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri with minors in political science and history. She also received a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of Florida.

Suzanne spent many years working in commercial news as Producer and Executive Producer in cities throughout the country before coming to WFSU in 2003. She is a past chair of the National Educational Telecommunications Association’s Content Peer Learning Community and a member of Public Media Women in Leadership organization.

In her free time, Suzanne enjoys spending time with family, reading, watching television, and exploring our community.