Mundi the elephant has been at a refuge in southwest Georgia for one month. She came from a Puerto Rican zoo that was in such bad shape, its animals were being moved to sanctuaries on the continent under order from the U.S. Department of Justice. Mundi had been the zoo’s star attraction, and her departure prompted so much controversy that armed federal guards saw her off the island. Now her home is an idyllic one.

NPR reported Wednesday on the scene in Mayaguez when Mundi left. People lined the streets to say goodbye. Carol Buckley, the founder and CEO of Elephant Aid International, had come to Puerto Rico to accompany Mundi to the refuge in Attapulgus, Georgia, on the Florida line.

After 35 years of living in a quarter-acre with no other elephants, Mundi met Bo and Tarra, with whom she’s now sharing 850 acres. At first, she was in a separate enclosure. But they could see each other and started getting along quickly, as Buckley pointed out.

“I’m kind of in shock,” she said. “I wanted to feed Mundi and Tarra close together. And so, I fed Tarra over here. She picked up her food and brought it right over to the fence-line here so she could be eating with Mundi. So, you tell me what that means. I think that is really good.”

Soon Mundi wasn’t separated from the others. The refuge says Tarra has become a big sister and mentor to Mundi, while Bo is her playmate. He and Mundi recently spent over an hour playing in a mud wallow together. The public can watch the elephants on the refuge’s YouTube EleCam.

The Georgia sanctuary is the vision of Carol Buckley, who met Tarra in 1974 when the elephant was less than a year old. Tarra then belonged to the owner of a tire store, who used her to advertise the place. Buckley ultimately became an advocate for elephants worldwide, and the retirement home in Attapulgus is based on her experience of their needs. It’s Mundi’s home now.

“The goal has always been that when she [Mundi] is comfortable, then she will be out in the 100 and the 750 with them [Bo and Tarra],” Buckley said. “But it would be inappropriate for us to rush it because we want to see them together….our job is to observe,” she said as Bo insistently trumpeted behind her.

Attapulgus was selected for the refuge because its climate allows the elephants to be outdoors most of the time, almost year round. The refuge has not only the big mud wallow, but rolling hills, spring-fed lakes, forests, pastures, creeks and streams. The elephants don’t need the barn much. But when it’s cold, their barn has sand floors four feet deep to avoid arthritis and other ailments common to elephants who stand on concrete most of the time.

Staying close, but respectful

Phil Kiracofe, a retired law enforcement officer from Tallahassee, helped build the refuge starting years before Bo became the first elephant to arrive. Kiracofe was named “Volunteer of the Year” last year by Elephant Aid International. He recalls the moment he first saw Bo years ago.

“When he stuck his head out the side door of that trailer and started stepping out, I said, ‘My God, he’s huge!’ He’s just such a regal animal,” Kiracofe said. “I mean, the guy is so impressive. A great, easygoing personality.”

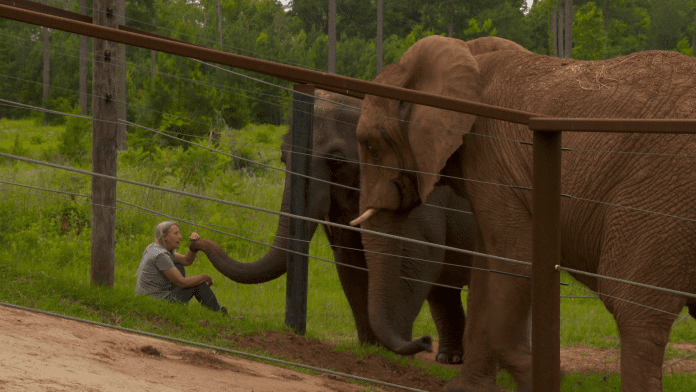

Kiracofe is quick to note that the refuge’s volunteers don’t have direct contact with the elephants. It’s one of the many protections that separate the Attapulgus refuge from others that claim to protect animals, while exploiting them for profit. Volunteers can observe the elephants from afar while they’re working, as Kiracofe does with Bo.

“Just to watch him and see how he started interacting with Tarra when she arrived sometime later, and now to watch how both of them interact with Mundi. It’s really fascinating to watch,” Kiracofe said.

Elephants are intelligent and social. They especially respond to reunions, the birth of a new calf or the death of a loved one. They’re capable of complex emotions. That sensitivity, said Buckley, is one of the reasons the preserve is off-limits to casual visitors.

“They can communicate with other elephants three miles away, through the air, through the ground 30 miles, they feel all the vibration and energy that comes into their area. Which is one of the reasons we’re not open to the public, because I can’t control people’s energy. I can say how I want you to be, that you stay calm and loving and don’t have expectations and don’t go, ‘Oh, the poor thing’ because they feel all of that. So, it’s best for them that it’s somewhat controlled.”

She says it doesn’t benefit the elephants to be open to the public. So, she brings in ‘key people,’ including reporters, to get the message out.

“That’s the goal,” said Buckley, “to get people to understand what are elephants, why are they in captivity, what should we be doing for them in captivity? So, with a small, select group of people who can actually reach the masses, we can then educate the public and help more than just our elephants. Help elephants worldwide.”

Practicing what she preaches

Part of Buckley’s work is international. In Asia, shackling elephants in chains has been universal for centuries, with crippling consequences for them. But Elephant Aid International has been able to establish chain-free corrals that eliminate the need for chains. In 2015, EAI convinced the government of Nepal to go chain-free at its 15 elephant facilities, freeing 54 elephants from their chains.

Buckley says she’s been blessed to have formed such profound bonds with not one but several elephants. In a 2018 interview with WFSU, when the refuge had yet to receive its first elephant, she said there were no words to explain those relationships.

“I’ve been able to be with them as they recover — and we say ‘rehabilitate’? It’s ‘recover.’ They’re recovering from the trauma that they experienced living in captivity,” she said. “And for them to open up and trust you while you are there with them, helping them work through it…it’s indescribable.”

A month ago, Buckley thanked the people of Puerto Rico for letting Mundi go to a better life. The elephant lives in paradise now, with the new friends she’s made along the way.

9(MDA4MzU1MzUzMDEzMTkyMzAwMzY5MjY1Mw004))

9(MDA4MzU1MzUzMDEzMTkyMzAwMzY5MjY1Mw004))