As an old neighborhood in Tallahassee is being demolished to extend a new road called FAMU Way, some call the changes progress. It’s the latest effort to make improvements to a poor area of the city near the historically black Florida A&M University. Others use the word gentrification, and it’s a move we’ve seen before.

“We don’t take enough emphasis and put it on history, you know, to take lessons so we can learn from what happened,” says Miaisha Mitchell, who grew up in Smokey Hollow, a neighborhood destroyed in the 1960s. “In the case of Smokey Hollow, just the idea that a whole set of people were moved — displacement really has a hardship on people. We don’t understand the factors that are involved, particularly when it comes to emotional trauma, when it comes to the loss of spirit and loss of family and loss of support systems.”

Not far from FAMU Way, Cascades Park now sits where hundreds of African American families once lived. The 24-acre park in the shadow of Florida’s Capitol draws visitors for its ponds, imagination fountain, and pet-friendly walking trails. Long before Cascades Park was envisioned, a neighborhood known as Smokey Hollow was there.

Urban Renewal Becomes Catch Phrase of the Day

The area around Tallahassee was dotted with plantations that operated through slavery. Many pieces of these former plantations evolved into black neighborhoods as freed men and their descendants chose to stay. Born in the 1890s, Smokey Hollow was one of those neighborhoods. It stood a few blocks east of Florida’s historic Capitol in a low dip in the landscape – a hollow. It was known for the persistent haze of smoke emanating from chimneys for heating and cooking.

“It was a community that had churches, businesses,” says Cicero Hartsfield, a Smokey Hollow resident. “Segregation was prominent. Blacks couldn’t live where they so desired, so it was one of the places where blacks lived.”

“It’s Important for people to recognize the impact of what happens to a lot of black communities.”

Cicero Hartsfield, Former Resident of Smokey Hollow

By the late 1950’s and early 60’s, the structures in Smokey Hollow were aged and many looked ramshackle. A two lane highway was widened into a broad boulevard, Apalachee Parkway, with a majestic view leading right up to the Capitol building — and cutting right through Smokey Hollow. To white citizens working or living on the hill, the neighborhood looked like a slum.

Urban renewal was the catch phrase of the day, according to local newspaper accounts. A possible expansion of the Capitol complex percolated with a grand vision of a campus-like array around the Capitol building. A referendum was held, and the state exercised eminent domain. Smokey Hollow residents were told to leave.

“It’s important for people to recognize the impact of what happens to a lot of black communities. They don’t see it because it’s not happening in their community,” Hartsfield says. “As a result, you don’t realize how many people may have lived in one of these small houses.”

A Black Neighborhood is Bulldozed in the Name of Progress

Smokey Hollow went under the bulldozer, ostensibly to make room for a much needed growing Capitol infrastructure. But just one government office is all that was immediately built in the area. The Department of Transportation building broke ground in November of 1964. Time went on, and not a lot happened with the remaining land. The view approaching Florida’s Capitol was magnificent, but the community of Smokey Hollow was gone.

“When part of my family left here, we scattered. Some went to the Bond community, some went to south side areas, some went to the north side in the Frenchtown community and Springfield area,” Mitchell says. “So naturally, that separation caused us to not be together as often. I still see a lot of that happening now, you know, with families who have been displaced. Many families are homeless. You know, that’s what I think led to a lot of the homelessness — the movement of the people from this area.”

“That separation caused us to not be together as often. i still see a lot of that happening now, you know, with families who have been displaced.”

Miaisha Mitchell, Former Resident of Smokey Hollow

Public housing projects started springing up around town as an answer to urban renewal. Smokey Hollow residents dispersed and moved to areas they could afford – and were allowed. Many moved south of the railroad tracks to an area known as South City. Others went to Frenchtown, but gentrification began there in the 1990’s.

“I think that the term gentrification doesn’t exist for no reason. We’ve watched it in DC, we watched it in Harlem, we’ve watched it all over the nation, and we’re watching it in Tallahassee, Florida,” says Christic Henry, Tallahassee-Leon County Council of Neighborhood Associations. “We’re watching communities that have been legacy communities, African American communities, and there’s a knowledge that where African-Americans dwell are some of the most valuable places in a community because we tend to be in the central of the city where accessibility is maximized because it’s a need.”

Public Housing Gets a Boost as Gentrification Takes Hold

As FAMU Way is extended, a South City housing project is being renovated and expanded to double the living space. The area sits about two miles south of the old Smokey Hollow.

“Early on, we were talking about urban renewal and eminent domain and, you know, the government could come in and take the property if they wanted to,” Mitchell says. “Now we’re talking about gentrification and red lining and all these things, but they’re all related to certain systems – housing, rough income, things of that sort.”

“Many of them have been in generational cycles of survivalism that just have not been broken,” Henry says. “Those are things that as a community we have to speak to and we have to own. We can’t just sweep it under a rug and say, no, that’s not the case. No, it is the case. The most vulnerable citizens are negatively impacted by eminent domain for the most part. So we have to be at the table when these decisions are made.”

“We don’t take enough emphasis and put it on history, you know, to take lessons so we can learn from what happened.”

Miaisha Mitchell, Former Resident of Smokey Hollow

Fifty years after the demise of Smokey Hollow, the City of Tallahassee completed construction of Cascades Park. It includes the Smokey Hollow Commemoration, featuring three open air Spirit Houses as symbols of the old shotgun houses that filled the neighborhood.

“When I think about lessons that I’ve learned, I know that it’s important for us to keep up on what’s going on in our legislature, to keep up with what’s going on in our local community government, to be a voice,” Mitchell says. “The people in Smokey Hollow didn’t have much of a voice, you know, the ones who were on my side of the track. We didn’t have enough to say about the legislature or new things that were coming to take down a shanty family’s home.”

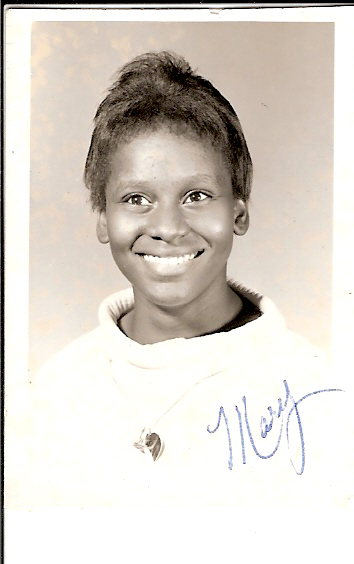

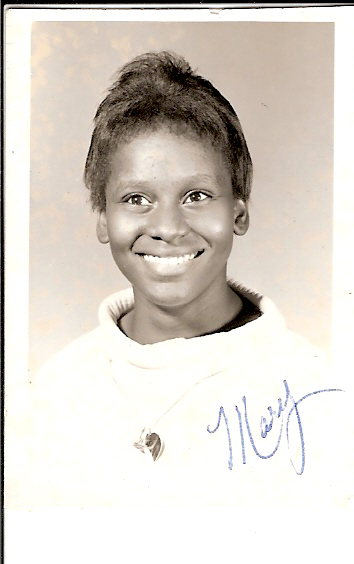

The neighborhood barbershop, which served as a community gathering spot, has also been preserved and put on display. A written collection of oral histories about the Smokey Hollow community was recently published, and more photos have been collected and released on the state archives digital memory project. Efforts continue to preserve the memories of Smokey Hollow – as the cycle of urban renewal continues.

Gina Jordan is the host of Morning Edition for WFSU News. Gina is a Tallahassee native and graduate of Florida State University. She spent 15 years working in news/talk and country radio in Orlando before becoming a reporter and All Things Considered host for WFSU in 2008.

She left after a few years to spend more time with her son, working part-time as the capital reporter/producer for WLRN Public Media in Miami and as a drama teacher at Young Actors Theatre. She also blogged and reported for State Impact Florida, an NPR education project, and produced podcasts and articles for AVISIAN Publishing.

Gina has won awards for features, breaking news coverage, and newscasts from contests including the Associated Press, Green Eyeshade, and Murrow Awards. Gina is the 2019-20 president of the Florida Associated Press Broadcasters Board of Directors.

In her free time, Gina likes to read, travel, and watch her son play sports.

Follow Gina Jordan on Twitter: @hearyourthought.