Main article by Suzanne Smith, 2023 photos by Freddie Hall.

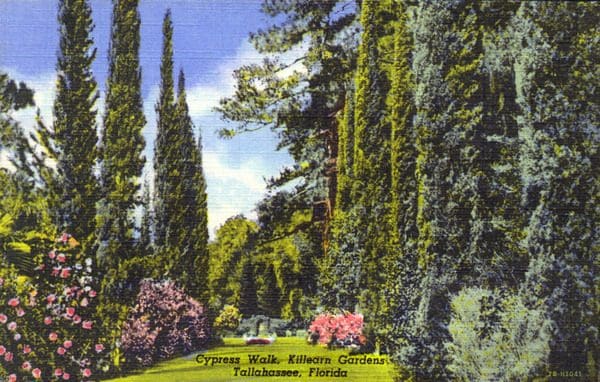

On April 6, 1953, the land most of us know as Maclay Gardens became part of the State of Florida Park System. At the time, the 307 acres were called Killearn Gardens and it was donated by the family of Alfred Barmore Maclay, Sr.

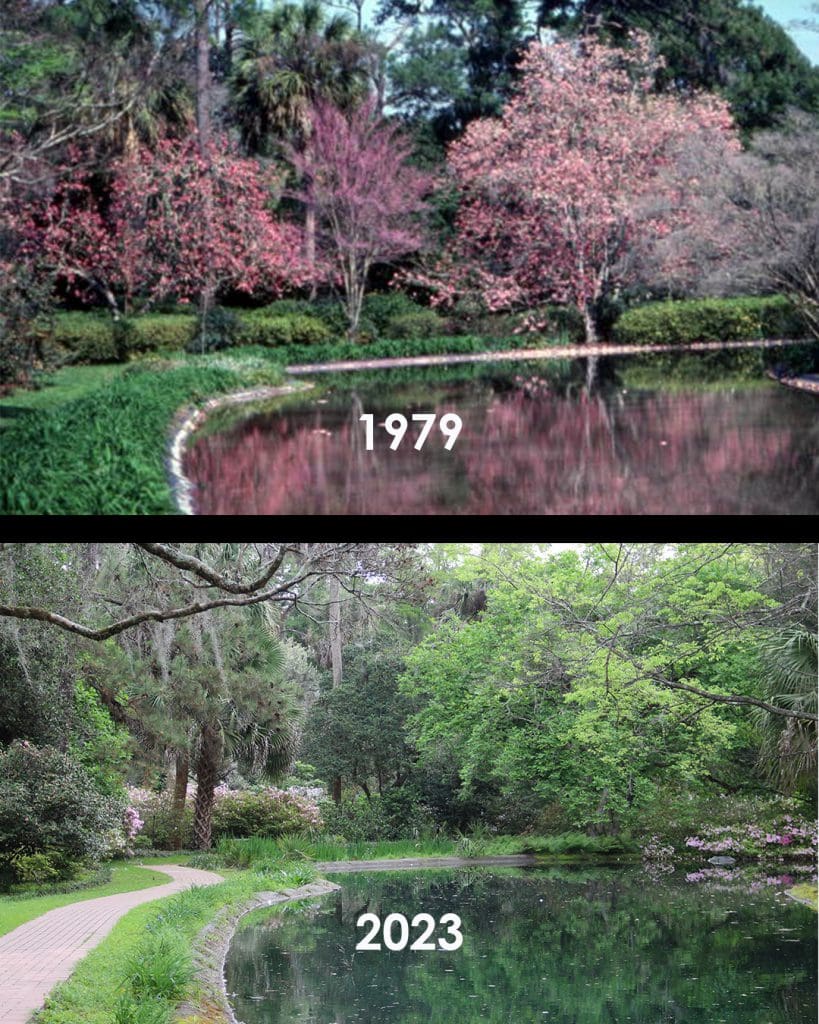

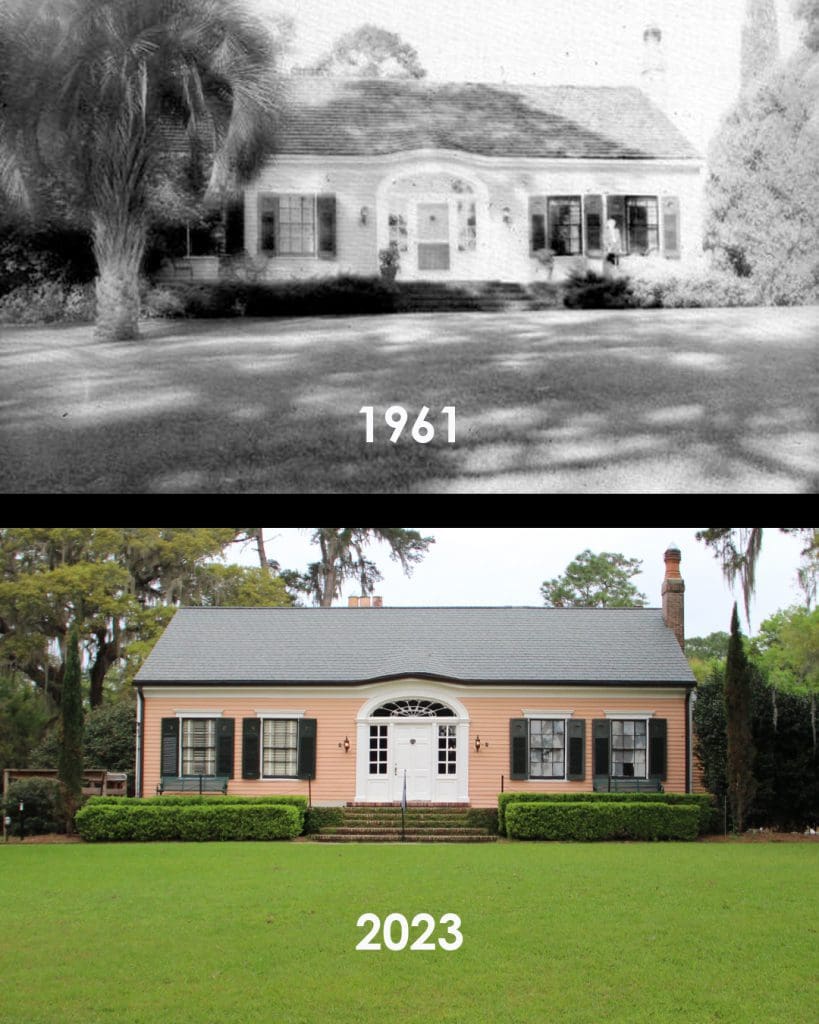

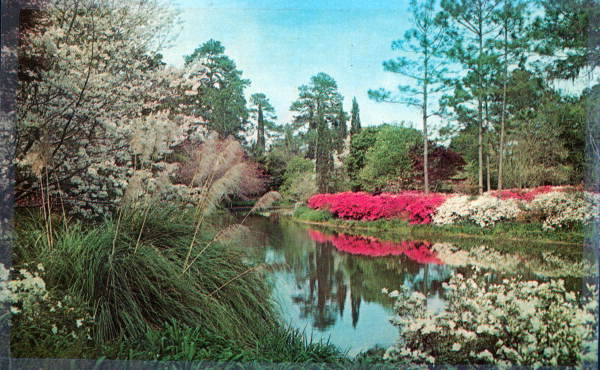

Now and Then

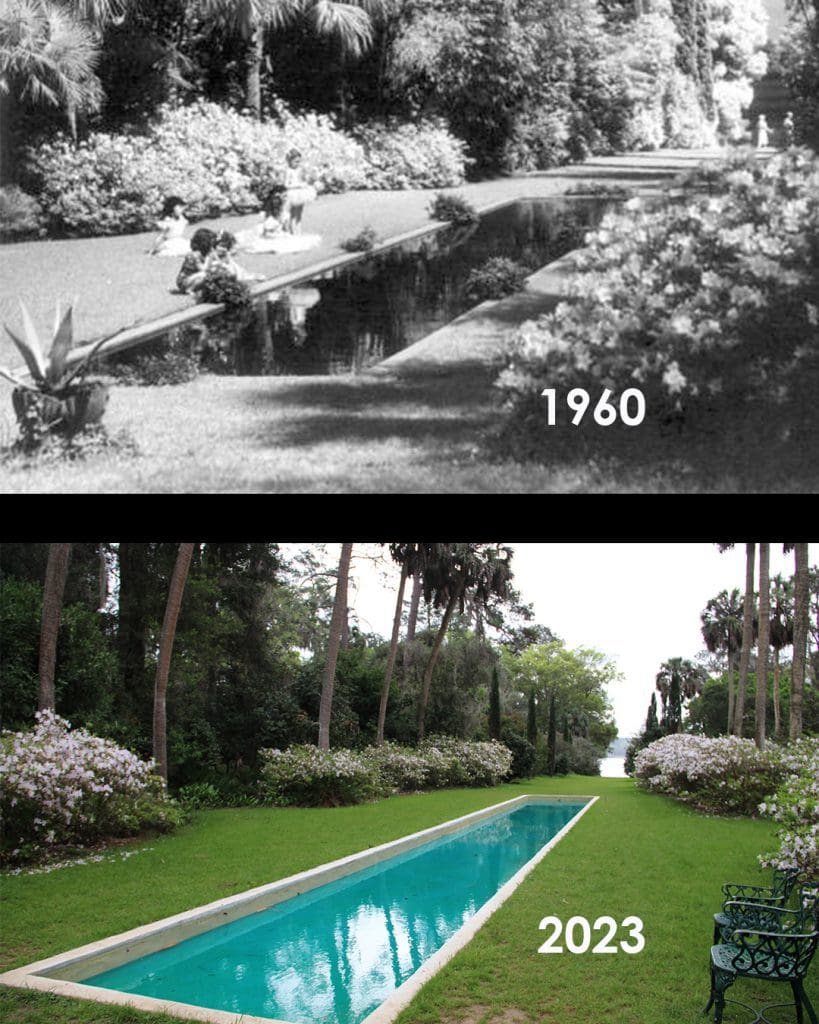

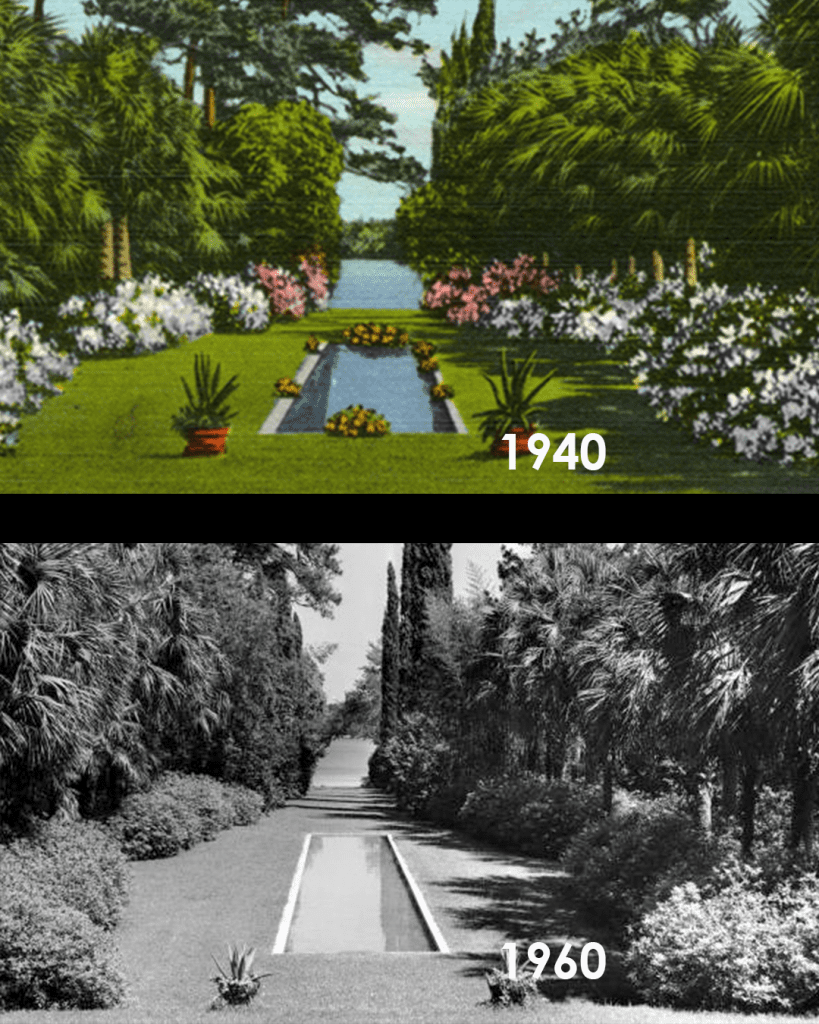

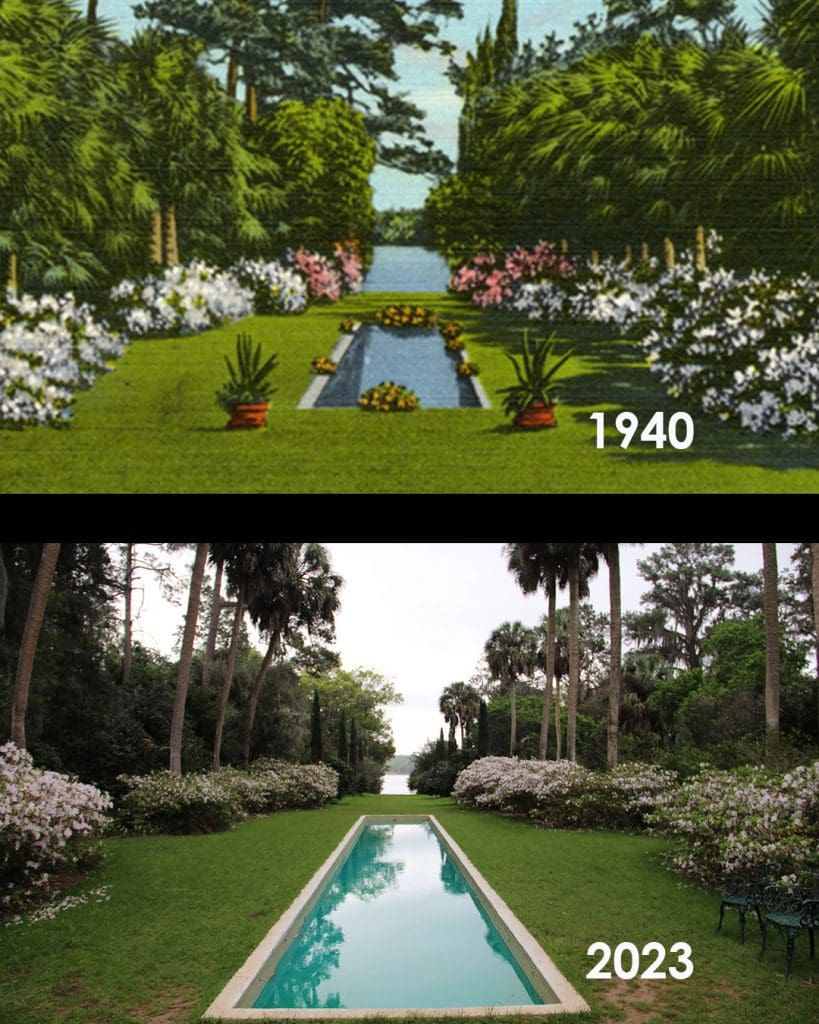

To walk around the Maclay Gardens State Park today is to experience one man’s vision. A vision that grew from a small seed to acres of vibrant colors. It is a vision that has endured and grown over the decades. Thanks to many photos from the State Archives of Florida, we have images of what it looked like in the past. And thanks to WFSU’s Freddie Hall we have images of those same locations today.

Viewpoint | A photographer’s vision of the Gardens through the years

By Freddie Hall

On March 10, 2023, I went out to shoot photos at Maclay Gardens State Park, which was previously known as Killearn Plantation and later Killearn Gardens. I have been out there many times over the years, but that information was new to me.

The State Archives of Florida’s website, Florida Memory, provided me with some great historical photos of the garden throughout the years. Some were in color while others were in black and white. There were even postcards among the photos. All of those pictures were a starting point for this “Now and Then” photo series.

Seeing the transformations, or even the same look of certain layouts, was very cool and interesting. The gardens have been maintained for decades and made to look a certain way out of respect for the history behind their creation. That makes it feel really special.

Of course, the azalea flowers were in full bloom while I was there. I had to spend some time taking photos of these colorful beds. I hope to go back out again to capture more of the scenery in the near future!

The Story of the Gardens

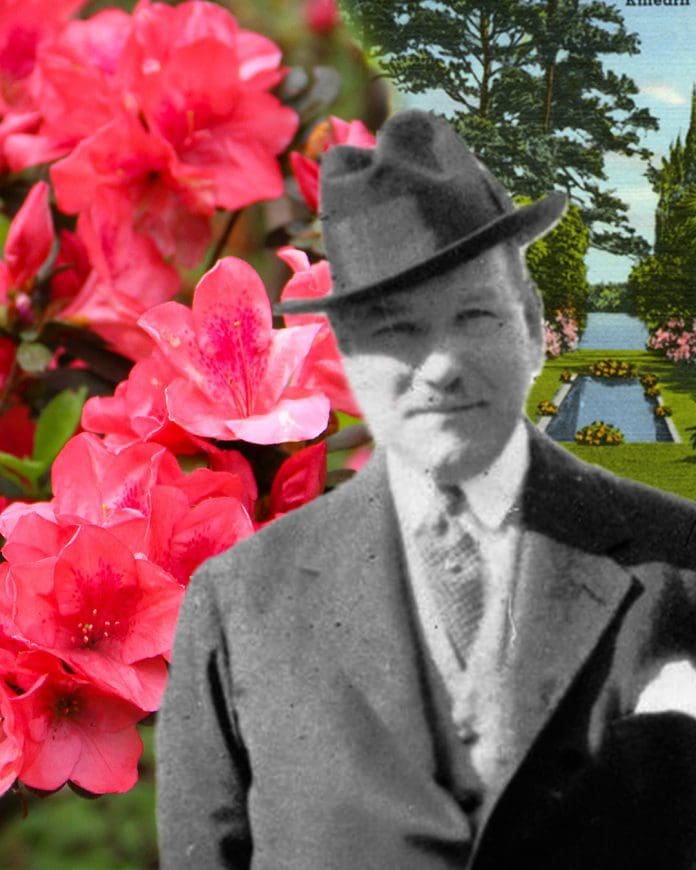

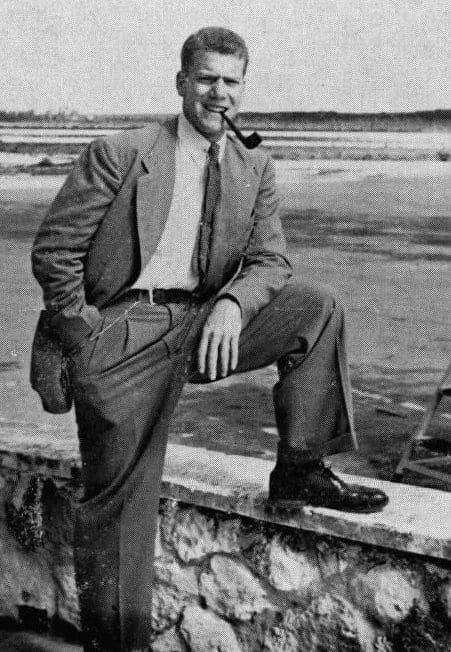

Who was Alfred Barmore Maclay, Sr.?

Alfred B. Maclay, Sr. was born in Manhattan on June 3, 1871, and grew up in a family that didn’t have to worry about money. His mother, Georgiana, was the daughter of one of the owners of the successful Knickerbocker Ice Company. His father, Robert Maclay, not only took over as President of that ice company when his father-in-law passed away but was also president of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, a successful investment company in New York.

The younger Maclay was reportedly 16 when he enlisted in the Army and served during the Spanish American War, reaching the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. After the war, while Maclay did spend a few years learning the various family businesses, he decided to focus on other interests, mainly horses. He initially exhibited, showed, and bred horses. Maclay founded and was eventually President of the Association of American Horse Shows (later called the American Horse Show Association and then the U.S. Equestrian Federation) which held competitions at Madison Square Garden. He was also on the board of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. In 1933 Maclay started an annual horse competition, the ASPCA’s National Horseman Championship. It is still held in his name today.

Maclay married Louise Fleischmann at her mother’s New York home in 1919. Louise Maclay had grown up visiting the Leon County area. Her brother, Udo Fleischmann, was owner of Welaunee Plantation. The new Mr. and Mrs. Maclay settled into their home they called Killearn Farms in Millbrook, New York and had two children, Alfred Jr., and Georgiana.

In addition to his work with horses, Mr. Maclay was also interested in raising dogs. His obituary in the New York Times said he was the first in America to import a Shetland sheepdog and “at one time he was the most extensive breeder of the Dandie Dinmont Terrier in the United States.”

The beginning of Killearn Plantation

The Maclay family made a big change in their life in 1923. On a trip to Leon County to visit Louise’s brother, Udo Fleischmann, Alfred Maclay finally saw the beauty his wife had experience when she visited the area as a child. He decided he liked the region too.

The Maclays bought the Lac-Cal plantation and renamed it Killearn Plantation. Maclay continued to purchase additional land and eventual grew it from a 1,935 acre spread to approximately 4,000 by 1930.

The family alternated their time between Florida and New York. They visited Killearn Plantation in Tallahassee from November through April and then would spend the rest of the year at Killearn Farms in New York. The Killearn name for both homes came from a village in Scotland where one of Alfred Maclay’s ancestors had been born. The National Horseshow website says Maclay was so attached to the village name, that all his competitive Fine Harness horses “had ‘Killearn’ in their name.”

Planning and planting the Garden

While Maclay focused on horses up north, he focused on plants in Tallahassee. Maclay’s father had been part of creating the New York Botanical Gardens and Alfred Maclay had an interest in flora as well. At his new southern home, Maclay focused on adding plants and trees that would bloom during the time the family would be visiting, creating an oasis filled with camellias, azaleas, and more.

Maclay hired Fred J. Ferrell as a full-time Supervisor of the gardens in 1924. He worked for the Maclays, and later the State Parks service, on the property for the next 49 years.

According to the National Register of Historic Places Registration form for the Gardens, Fred’s wife, Jessie Ferrell, said the land looked very different in the beginning of Maclay’s ownership than it does now. Mrs. Ferrell said that when she and her husband first arrived a year after the purchase, Maclay had already managed to put in the first bed of about 30 azaleas on the land. That was just the beginning. Maclay would leave instructions for Fred Ferrell to make changes to the land while Maclay and his family returned to New York. Jessie Ferrell told State Park employee Beth Weidner in 1984 that “Mr. Maclay would go out with an armload of stakes – white, paddle-like with a place at the top to write on – and put them where he wanted plants to go, with the variety name written on the stake. When he got done here would be a year’s worth of work for Fred to do.”

The Maclays also had several tenant farmers on the land. Cotton was still the main crop. Some of the tenant farmers also worked for the Maclays part-time while others from the area were employed full-time. The garden’s registration form to the National Register of Historic Places says wages for employees were not high. A typical wage was one dollar a day. Some of the full-time staff lived on the property rent free. The form says Maclay added new buildings or repaired old ones for employees.

Some of the staff who worked for the Maclay Family. It includes cooks, caretakers, gardeners and farm hands. Date of Photo Unknown. According the State Archives of Florida floridamemory.com website, in the back row: Richmond Heights, Rufus Hayes, Jim Sawyer, Willie Gallon, Henry Sawyer, and Depew Smith. The women standing: Annie Sawyer, Harriet Vernon, and Florence Edwards. The women kneeling are Pinky Sawyer and Elizabeth Gallon Rollands (State Archives of Florida)

The Aunt Jetty and other plants

Maclay bought many plants from his neighbor and friend, Breckinridge Gamble, over the years. Gamble owned the nearby Camellia Nursery, where Dorothy Oven Park exists today. One of the first and most famous camellias to be planted in the Maclay garden came from the front yard of the Gamble home. Maclay bought the already 80-year-old plant for $75. The variety was called the “Aunt Jetty” after a nickname for Gamble’s aunt, Angelica Robinson Gamble. This plant had originally been brought to Florida from up north. That Aunt Jetty continued to grow for decades on the Maclay property. The plant was estimated to be over 200 years old when it died around 2011.

Other plants and trees soon joined the Aunt Jetty under Maclay. The rare Chapman’s Rhododendron, named after the Apalachicola Botanist Alvan Wentworth Chapman, was found and transplanted into the garden. Meanwhile, Fred Ferrell grew rare Torreya Trees from seeds and added them to the garden as well.

Maclay Hospitality

The Maclays would often host parties for out-of-town visitors on the land. In addition to creating the gardens, Maclay also hosted quail hunts. Even though he focused on the garden, he still had a stable full of horses on the property.

As the gardens expanded, the Maclays would open the grounds and house to local visitors. A 1945 article in the Daily Democrat said that starting around 1940, the Maclays would open the grounds for a few days each year to raise money for “various charitable organizations.”

Alfred Maclay died May 27, 1944, in Manhattan after a long illness.

The Journey from Killearn Plantation to Killearn Gardens to Maclay Gardens

Welcome to the Gardens

After the death of Alfred Maclay, the remaining Maclay family made a major change to their private garden world. In 1945, Alfred’s widow, Louise Maclay, decided to open the gardens at Killearn Plantation to the public without charging an entrance fee. For four days in March that year, people were able to explore the paths and the flowers for free.

The following year, Louise Maclay turned “Killearn Gardens” into a business. From December 1, 1946, to April 15, 1947, the garden section of the property was open to the public. The local paper called it a “New Tourist Attraction” for the area. It wasn’t wrong. In January of 1947, the Duke of Windsor (formerly known as King Edward of England) and his American wife, Wallis Simpson, visited the grounds while traveling in the area. Mrs. Maclay opened the Gardens again for the 1947-48 and 1948-49 seasons.

But in the 1949-50 season, except for a few days in January, the gates to the garden stayed closed to the general public. Louise Maclay said she didn’t have enough time to devote personally to opening the gardens. In the Spring of 1951, through Florida State Senator LeRoy Collins, the Maclay family made a big announcement. They were going to donate the Gardens to the state of Florida in memory of the late Alfred B. Maclay.

It took two years to secure state approval and funding for park maintenance and to work out the details of the agreement. Among those details, Louise Maclay would continue to live on the property for several years and pay rent to the state. There was also grief during that time. Louise and Alfred’s son Captain Alfred B. Maclay, Jr. died in 1952 after suddenly contracting Polio. On April 6, 1953, the deed to Killearn Gardens consisting of 307 acres was officially transferred to the Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials.

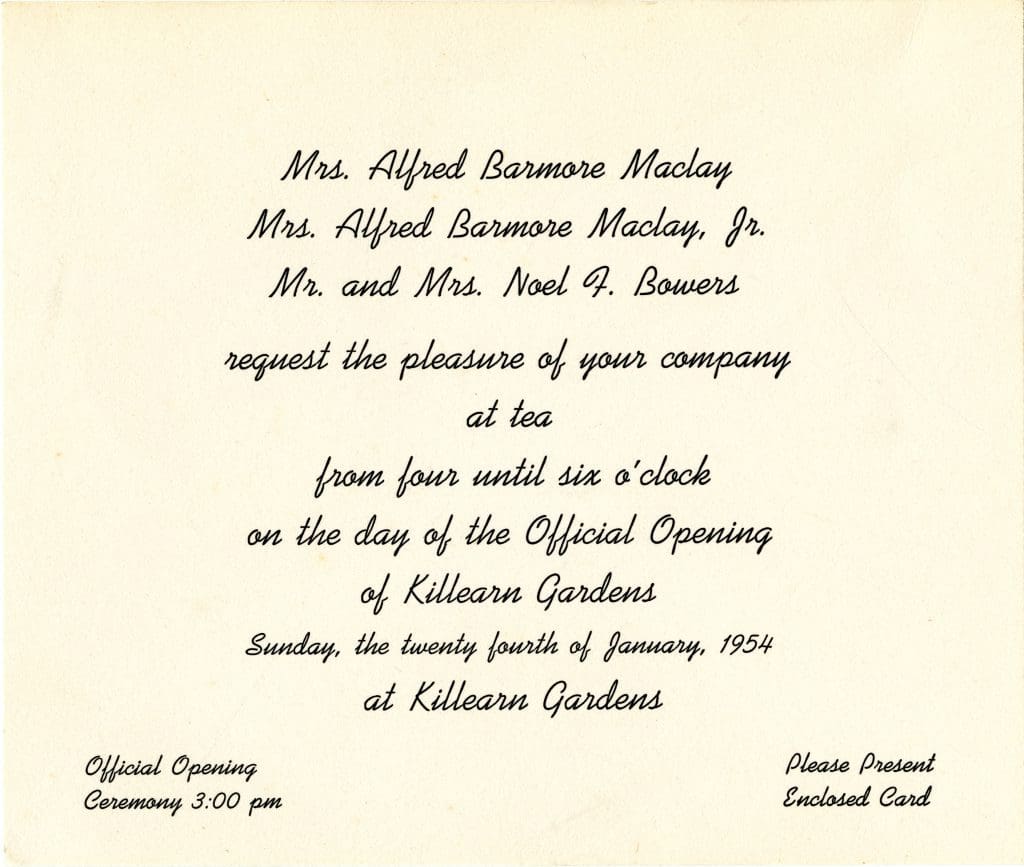

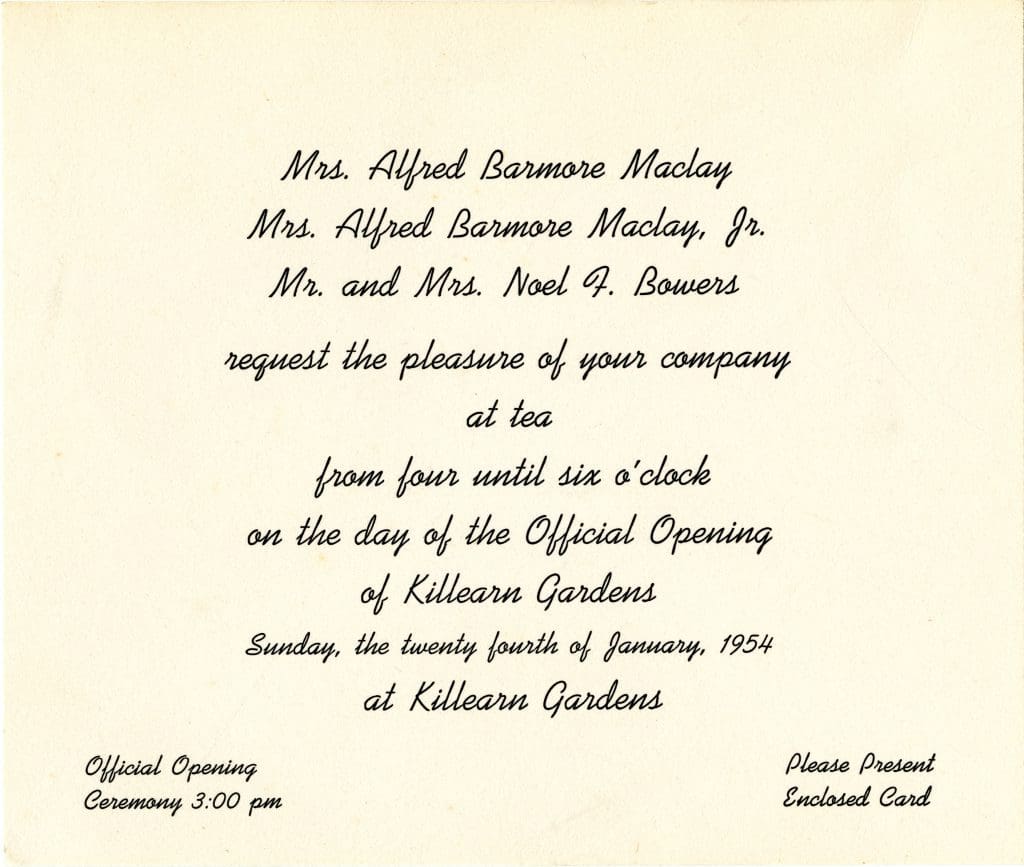

The Official Opening ceremony of Killearn Gardens State Park took place on January 24, 1954.

Another name change

On March 17, 1956, Senator Collins, Mrs. Maclay, and her daughter Georgiana Maclay Bowers dedicated a special plaque within the park in honor of Alfred Maclay Sr. The Park’s name remained Killearn Gardens even though some suggested that it should be named after Maclay.

In 1961, Mrs. Maclay moved out of the main home to return to New York. At that time, Fred Ferrell, who continued his work at the Killearn Gardens under the State of Florida, told the Daily Democrat that Mrs. Maclay had kept an eye on the new owners after the transfer. “She walks over the gardens whenever weather permits”, Ferrell told reporter Hallie Boyles. “Sometimes 20 miles in a single day. She has watched closely each development.”

Louise Maclay continued to pay attention to more than just the developments at Killearn Gardens. In 1965, a new subdivision was being built across from the park on Thomasville Road. Its proposed name was “Killearn Estates.” Mrs. Maclay was not pleased. The State Parks system and Mrs. Maclay agreed to change the name of the park in honor of her late husband. It has been called the Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park, or Maclay Gardens for short, ever since. It is interesting to note that Louise Maclay agreed to pay for the changing of the front signs.

Louise Fleischmann Maclay passed away in September 1973.

A Birds-Eye view of Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park

Video Edited by Devin Bittner, Drone video by Jon Manson-Hing

The land before Maclay

Native Americans, Spain, the British and more

In 2002, Maclay Gardens was listed as U.S. historic district under the name the “Killearn Plantation Archeological and Historic District.” Of course, the story of the Maclay family and the creation of the Gardens is just one part of a very long history of the area.

At the time when Europeans first arrived, the Apalachee had built homes, towns, and their capital in the area. Spanish missions, like Mission San Luis, were then built to convert the Apalachee and settle the region. Over time, multiple European flags flew over the land making permanent settlement difficult. After the first Spanish rule, England controlled the area during a time that includes the American Revolution. Under British rule, many Spanish began to leave the area while British loyalists escaping American rule moved into the area.

In 1783, the government in charge flipped again, and the land was turned back over to Spain. By then, many Creeks, Seminoles, and black men and women escaping from slavery in the American South had also moved into Spain’s “La Florida”. Later, America’s General Andrew Jackson crossed into the Spanish territory during the war against the Seminoles in 1818. Jackson and his troops traveled either on or near the site of the future Maclay Gardens on their way to burn out the Native Americans who lived on the shores of Lake Miccosukee. In 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty decreed that Spain would give East and West Florida to the United States, which finally took control in 1821.

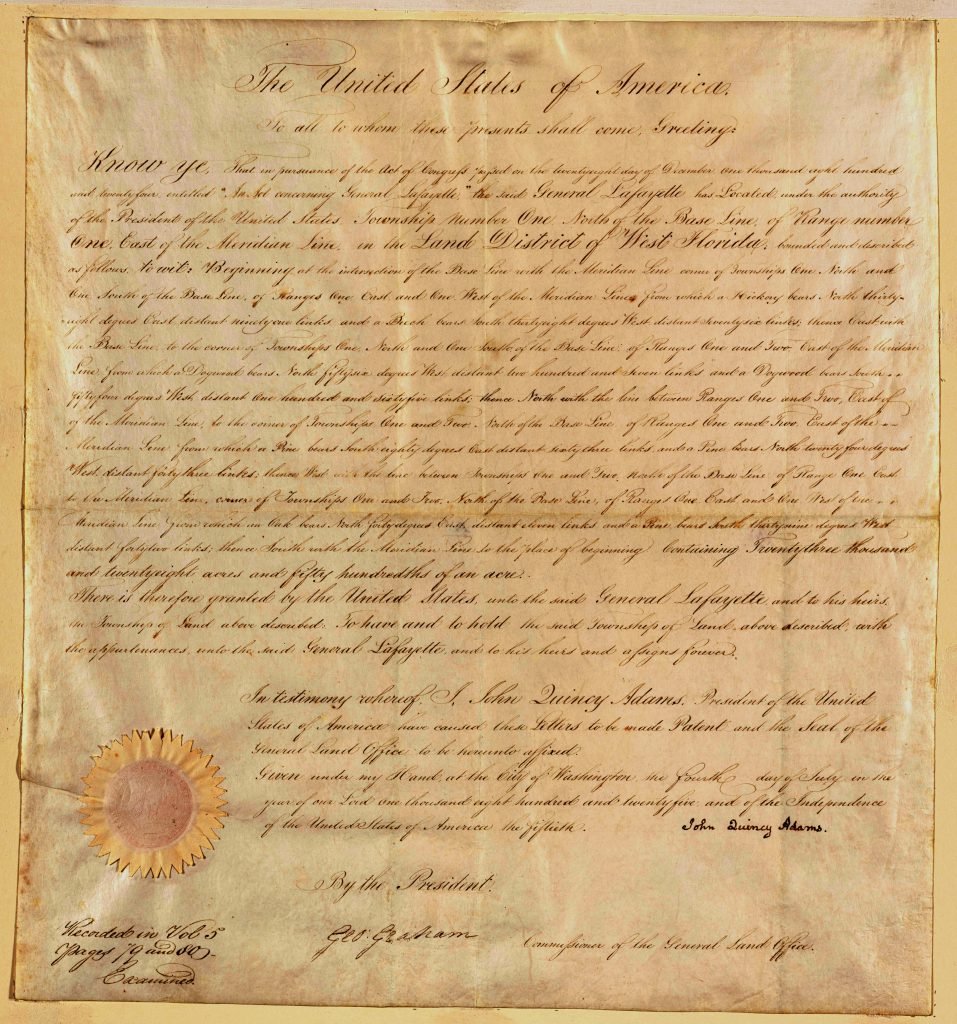

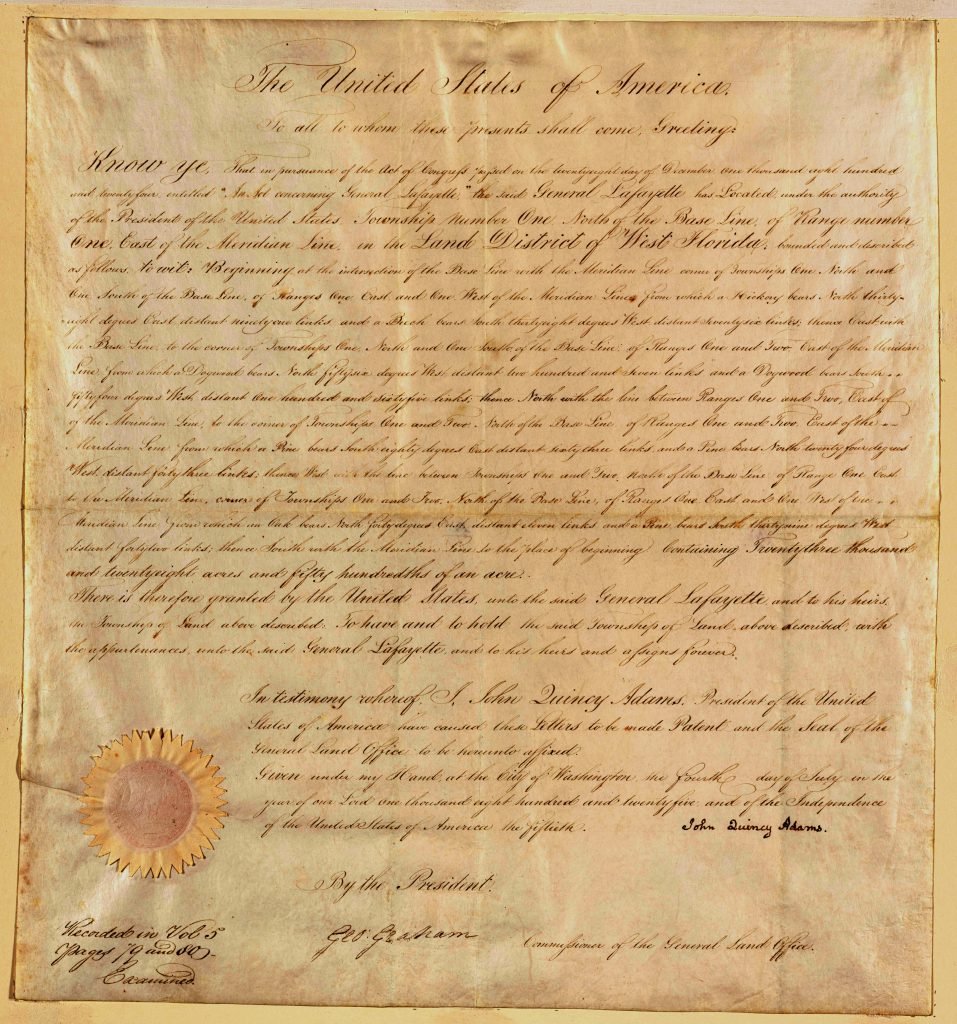

The Territorial Legislature of Florida named Tallahassee a city and the capital in 1824. The first settlers arrived in the still-forming city in April of that same year. In 1825, the U.S. President at the time signed a document that still impacts many names and the history of our area. It was called the Lafayette Land Grant.

Marquis de Lafayette and the Lafayette Land Grant

Gilbert du Motier, The Marquis de Lafayette, was from France and served as a General on the side of the Continental Army during the American Revolution. During the war, he gave America a badly needed $200,000, which would be worth about 7 million dollars in 2023. Considered a hero by the American people, the Marquis received some land and money from the Americans after the war. However, his own finances were in trouble following the French Revolution. On the symbolically chosen date of the Fourth of July in 1825, President John Quincy Adams signed a Land Grant that gave the Marquis $200,000 and a 36-square-mile area of his choosing.

The Marquis chose land north of Tallahassee where a friend of his, Richard Call, lived on the Grove Plantation. The Marquis’ new land was bordered on the Western side by today’s Meridian Road, stretched south to roughly today’s Lafayette Street, and then east to just past Lake Lafayette. His eastern boundary then cut north through the present-day Vineyards subdivision on Mahan. It continued north to Roberts Road (one mile east of Centerville Road). The northern boundary then cut through the middle of the current Maclay Gardens, ending on North Meridian Road near the current Maclay School. Check out this map of the Lafayette Land grant.

The Marquis never set eyes on any of this land, but he had ideas. He wrote to friends encouraging them to move to the area and grow vineyards, olive groves, and other European-type crops without slave labor. According to Kathryn T. Abbey in an article for the Florida Historical Quarterly in 1931 called “The Story of the Lafayette Lands in Florida,” an initial colony of 50 to 60 French “peasants” set up on a bluff overlooking Lake Lafayette in 1831.

Abbey writes that the group had trouble clearing the land and planting did not go well. That, combined with issues with the deeds, caused the dissolution of the colony. While many went back to France or moved to New Orleans, some did stay in the Tallahassee area. It is believed that at least some of those settled outside the Land Grant area in what became known as Frenchtown. It is still known by that name today. The land where Lafayette Park, Lafayette Street, and Lake Lafayette were located was all part of the Marquis’ original property and all named after him. So were the subdivisions Lafayette Oaks and Lafayette Meadows. Plenty of other non-Lafayette named neighborhoods are also on land that was also once part of the land grant. For example, if you live in Waverly, the southern half of Killearn Estates, Betton Hills, or Los Robles, then you live in an area that was once owned by the Marquis de Lafayette.

From the Marquis to Maclay

The Marquis didn’t plan to keep all that land for himself. Initially, he planned to sell about half of it, but by 1833 mounting debts forced him to start selling almost all of it. Lafayette died in 1834 and by 1856, his family had sold the rest of it.

Eventually, the northwest section of the Lafayette Land Grant became the southern part of the land owned by the Maclay family. But before it ended up in their hands, there were multiple other owners of various sections over the next one hundred years.

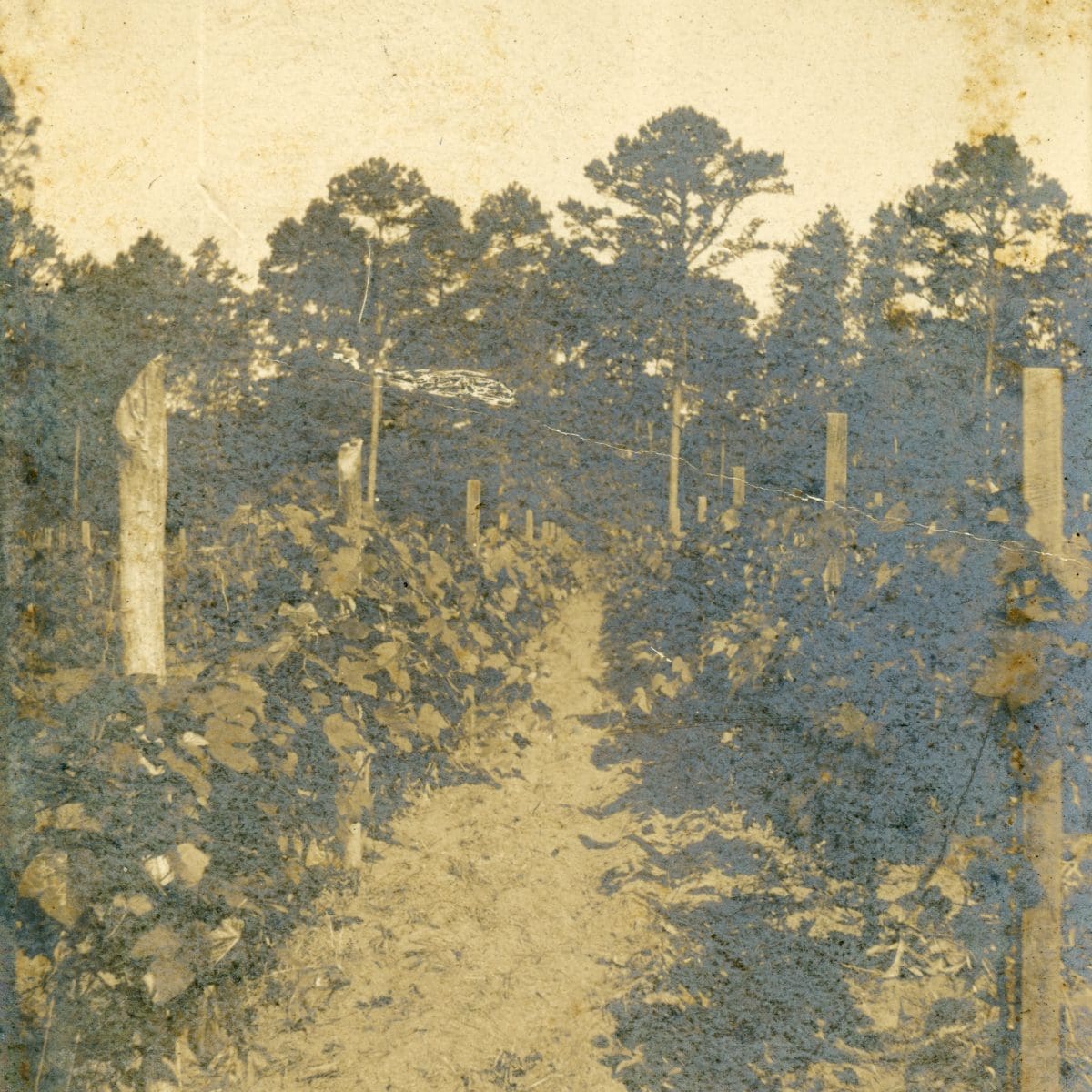

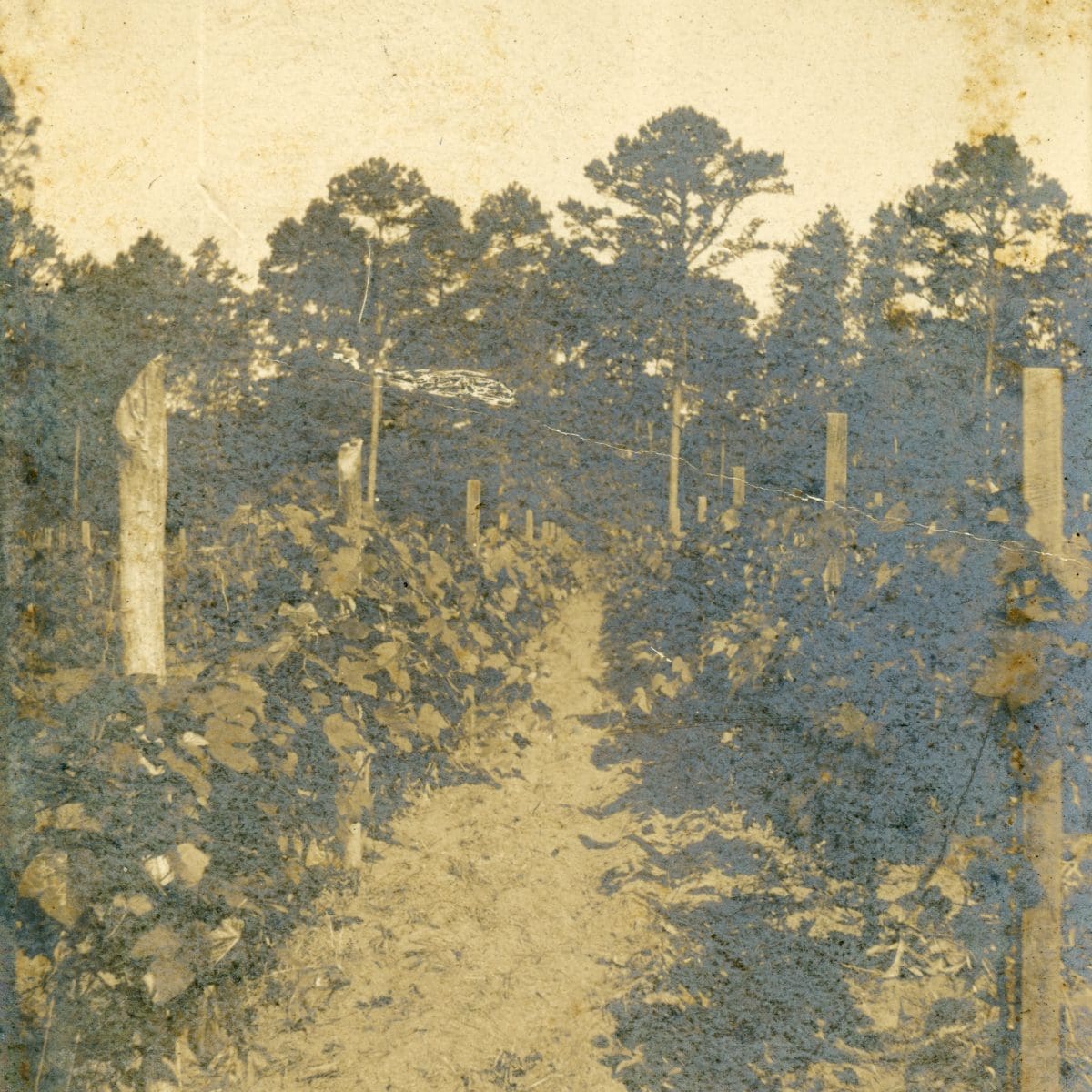

According to the Maclay Garden’s registration form to the National Register of Historic Places, several large plantations were developed in the area over the years. For example, in 1836, Hector Braden established Chermonie Plantation, which was later sold to Dr. John Adam Craig in 1839. Craig renamed it Andalusia Plantation. On both versions of that plantation there was slavery and cotton. After the Civil War, there was tenant farming and a lot of land in the area was sold off in Leon County. While Craig’s son, John, did keep Andalusia going until he died in 1885, he also sold off some land. About 20 acres of the plantation went to Frenchman and winemaker Emile Dubois. Dubois planted a vineyard on the shores of Lake Hall. He also had a vineyard at what is now Mission San Louis.

Quail hunting on former Cotton plantations became fashionable for Northerners after the Civil War. Starting around 1890, a man named John H. Law started to buy up land in the area. He eventually purchased enough land to create a 1,935-acre Quail hunting plantation he named Lac-Cal. The unusual name was made up using the first letters of each of his children’s names: Laura, Ann, Clara, Charles, Alice, and Lucy. After Law passed away, the land was sold to Alfred B. Maclay.

March 2023 Flowers at Maclay Gardens State Park

Photos by Freddie Hall

There is a lot of history explored in this story and much more we were not able to touch on in this article. Let us know what you think of this story or if there are areas you’d like us to dive into in future stories. Contact us at localroutes@wfsu.org.

Suzanne Smith is Executive Producer for Television at WFSU Public Media. She oversees the production of local programs at WFSU, is host of WFSU Local Routes, and a regular content contributor.

Suzanne’s love for PBS began early with programs like Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and continues to this day. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri with minors in political science and history. She also received a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of Florida.

Suzanne spent many years working in commercial news as Producer and Executive Producer in cities throughout the country before coming to WFSU in 2003. She is a past chair of the National Educational Telecommunications Association’s Content Peer Learning Community and a member of Public Media Women in Leadership organization.

In her free time, Suzanne enjoys spending time with family, reading, watching television, and exploring our community.