Originally published May 1, 2023

Updated May 1, 2024

May 1, 1833

Tallahassee’s May Day Tradition Begins

On May 1, 1833, Tallahassee’s long-running May Day celebration most likely took place for the first time, less than 10 years after the founding of the Capital city.

May Day events go back hundreds of years to Medieval Europe celebrations and Pagan festivals announcing the arrival of spring. Tallahassee’s version of May Day was held almost annually for 141 years before ending in the 1970s. At that time, it was the longest-running festival in the state.

Over the 14 decades it existed, the May Day celebration became a community tradition, occurring sometime within the first week of May and often with multiple events taking place over several days. The location eventually settled at Lewis Park under a giant oak tree that became known as the May Oak or the Lewis Oak.

There were also maypoles and May Queens. According to a publication by the Trinity United Methodist Church Historical Society of Tallahassee, the Queens were chosen going back to the very first year of the event. However, the information was not recorded because “the names of the young ladies were not printed in newspapers” in those days. Reverend Norman Booth recorded that Mary Antoinette Myers was crowned the May Queen in 1844.

In those early years, the city’s young people selected local girls to become the May Queen. In 1934, The Queens were chosen from the senior classes of Florida High and Leon High. After World War II, Leon High School became the regular sponsor of the event. From then on, the school’s student body chose the Queens from the girls of the Senior Class at Leon High School. In one notable election in 1958, it took three ballots for a young woman named Linda Gormley to beat a school newcomer by the name of Faye Dunaway. Dunaway lost by only 6 votes that year, but she had the last laugh. In 1977, Dunaway won an Oscar for Best Actress in the movie, Network.

Gormley, who beat Faye in 1958, wasn’t the only “Queen of the May” with an interesting backstory. In 1927, Marguerita Cawthon shaved her head the night before she was crowned. Reportedly, it was an effort to get revenge on her parents. They had previously punished her for sneaking out of the house one night. Cawthon was still crowned Queen that year, wearing a wig under her crown.

Other town institutions also held May Day celebrations over the years, choosing their own Queens. Florida State College for Women, Florida High, and Old Lincoln High all held separate events.

As Gerald Ensley described in a 2011 Tallahassee Democrat article, the May Day “tradition died in 1974” but he detailed that it had been on a downward spiral for a few years beforehand. It happened at the same time local schools were integrated in the area. In the spring of 1968, the all-black Lincoln high school closed. While Leon had been integrated in 1963 when a few black students began attending, with the closing of Lincoln, the number of black students increased at all the high schools.

In January of 1970, an article by United Press International (UPI), reported that the County’s School Board voted to discontinue the event at the recommendation of Leon’s principal, Robert Stevens, on the grounds that preparations were too time-consuming. The article went on to say that the board “denied the action had ‘racial overtones’ although there has been some criticism of the all-white tradition of the event” from black leaders. That criticism is still heard today about the ending of the event.

Ensley’s 2011 article also revealed some additional tensions between the various high schools in the years leading up to the end of Leon’s involvement. The principals of the newer Rickards and Godby high schools had also expressed concerns that only Leon was allowed to be in charge of the May Day celebration. However, neither of those schools took over the preparations after Leon stepped down. In fact, there were no sponsors in 1970 and the May Day celebrations didn’t happen that year.

The Tallahassee Democrat says that in 1972, the Sons of the American Revolution took over the sponsorship with a focus on elementary children instead of high school teens. Meanwhile, Springtime Tallahassee, begun in 1968 and held earlier in the spring, grew. Interest in the May Day celebration continued to drop and after the 1974 event, it ended for good.

In 1986, the May Oak in Lewis Park, estimated to be over 200 years old, collapsed and died. Its stump and a plaque remain in the park.

May 2, 1927

A modern hotel era begins

The Hotel Floridan officially opened on the Northwest corner of Monroe and Call Street on May 2, 1927. Going by the name Hotel Floridan as well as Floridan Hotel, it was the largest and most modern hotel of the times. It was also very much needed in the city of Tallahassee. Just two years before, a fire destroyed the very large and historic Leon Hotel on East Park Avenue. A group of local investors put together the plan for the Hotel Floridan under the name the Tallahassee Hotel Corporation.

Guests had been staying at the building for a month before the official opening day and all the rooms were already full on the day of the event. A public three-hour reception was planned with music provided by the Florida State College for Women’s College Orchestra. The hotel offered free tours of the building throughout the afternoon.

The 68 rooms were described as consisting of various comfortable sizes and all having between one and five windows with copper screens to keep out pests. Each room had its own bathroom with a shower or a tub. Plus, each room had its own telephone as well as electric fans, lights, and outlets. It was described as “modern in every detail.”

On the day it opened, the Tallahassee Daily Democrat dedicated their entire 32-page paper to the celebration. With the large headline “Hotel Floridan Formally Opens Today” and a large photo of the hotel’s manager M.J. Watts leading the coverage, the newspaper included articles about the flowers and explored the extra space on the first floor designed to be leased to four businesses. Meanwhile, businesses across town placed advertisements in the paper congratulating the city and the owners of the new hotel and wishing both the best of luck with the new endeavor.

While no set number of visitors was recorded in the local paper, the Daily Democrat did say “throngs” of people explored the hotel on the day of the opening. Legislators regularly stayed at the hotel over the years. One of the most well-known residents of the Hotel Floridan was Ruby Pearl Diamond, namesake of the Ruby Diamond Concert Hall. She began living in the hotel shortly after it opened and stayed there for decades.

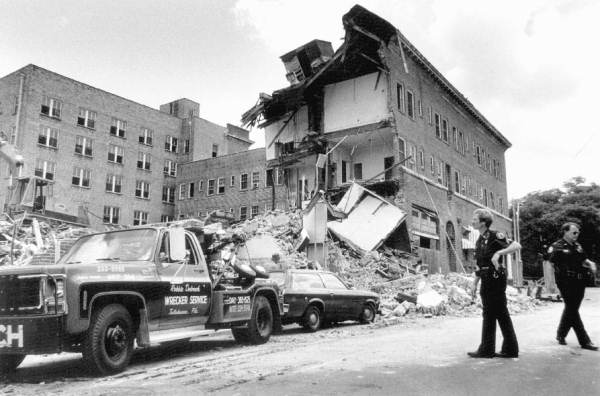

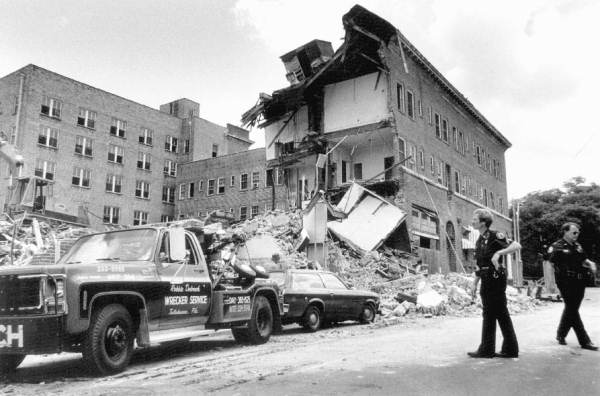

The hotel fell into disrepair and closed in the late 1970s. Demolition had begun in 1985 when one last dramatic moment happened. A 30-foot section of a wall unintentionally collapsed and landed on the truck of one of the construction workers. Doug Booher barely escaped the truck before bricks crushed the vehicle. Booher later used a crane to haul what was left of his truck out of the debris.

Today, the Aloft Tallahassee Downtown hotel stands in that same location. It was built in 2009.

May 3, 1971

NPR’s All Things Considered debuts to Tallahassee listeners.

In 1971, WFSU-FM was one of only two stations in Florida that was an original member of National Public Radio. WFSU’s radio station already had a long history by that point. It had begun back in 1949 and in 1970 became one of the 90 charter members of NPR.

On May 3, 1971, the first episode of “All Things Considered” aired for the first time and still exists to this day. ATC co-anchor and journalist Susan Stamberg recalled that NPR had held a staff contest to come up with the name for the program. NPR’s Operations Manager George Geesey came up with “All Things Considered.” The contest approach was used again in 1979 to come up with the title for “Morning Edition.” Stamberg says her favorite suggestion for the show wasn’t picked. A producer had submitted “Tomorrow We’ll Be Better.”

May 5, 1944

FAMC Student and Tuskegee Airman lost in WWII

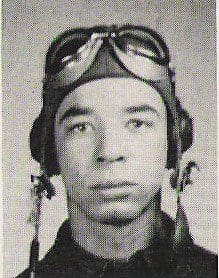

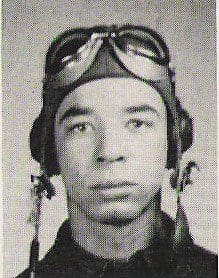

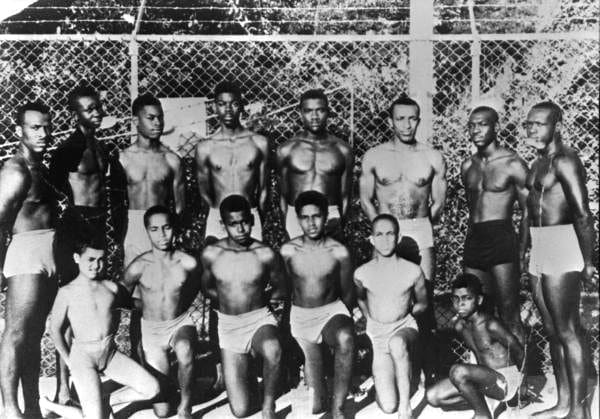

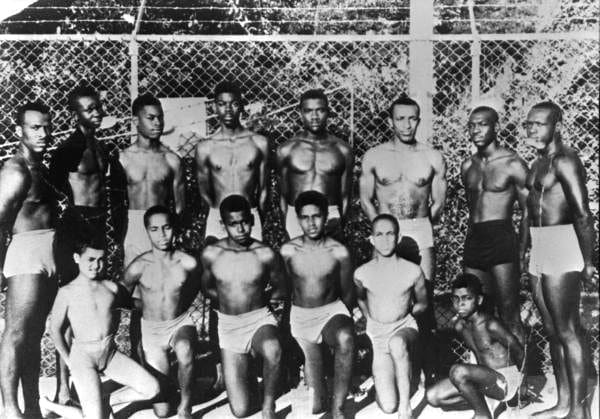

James Polkinghorne, Jr. had just finished his Junior year at Florida A and M College when he decided to enlist in the military on May 31, 1942. Polkinghorne became the first FAMC student to be accepted into the U.S. Army Air Corps and was assigned to the 301st Fighter Squadron. The 301st was one of four squadrons that made up the all-black 332nd Fighter Group known as the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II.

Polkinghorne finished his initial flight training in 1943. By the end of the year, he had been promoted to First Lieutenant and in 1944 headed to Europe with his squadron. According to the Commemorative Air Force Rise Above website, on May 5, 1944, Polkinghorne was assigned to lead a third of a 12-plane strike team attacking targets on Italy’s western coast. During the mission, Polkinhornes’s group and another descended below the clouds to attack, while the third remained above. As the two teams returned above the cloudbank, enemy fire from the ground followed them. The strike team realized Polkinghorne’s plane did not return.

He was declared missing, but Polkinghorne’s body was never found. Polkinghorne was declared dead a year later. In 1948, FAMC named the 170-unit planned to house veterans Polkinghorne Village. It was demolished in 2012. In 2014, a new 800-unit residence hall was built and called FAMU Village. The new village was renamed James Polkinghorne, Jr. Village in 2019.

May 5, 1960

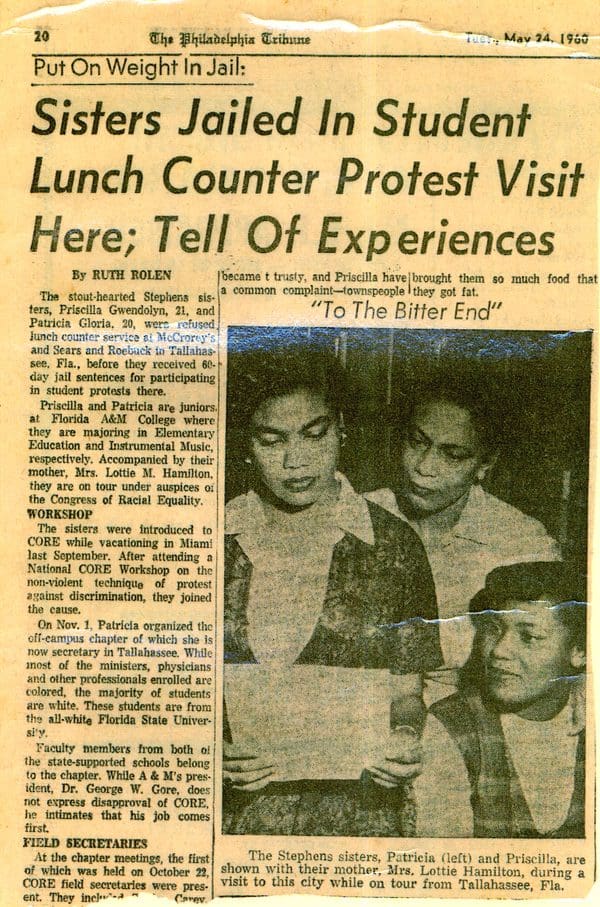

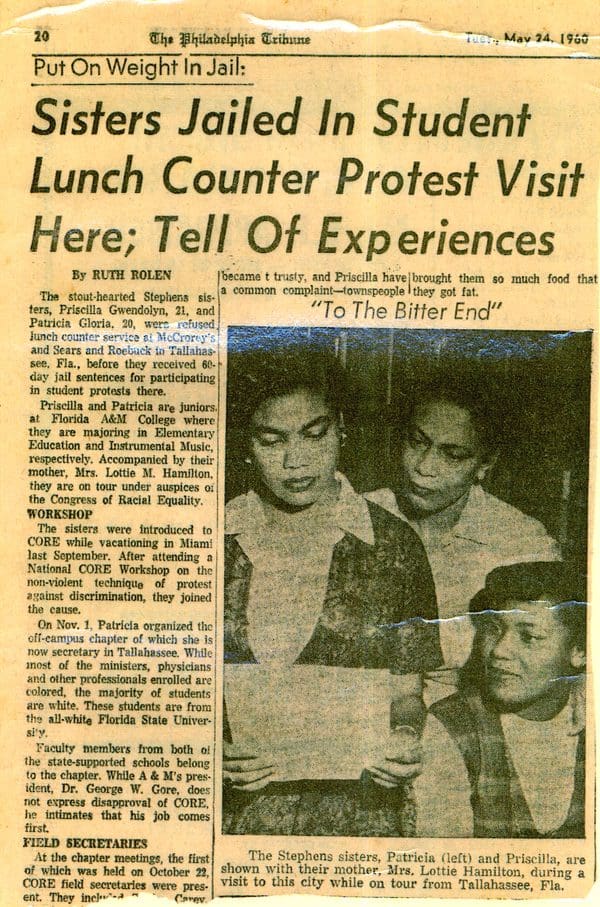

Sit-in protestors are released from jail

On May 5, 1960, the first Tallahassee protestors who had been arrested and found guilty of disturbing the peace for the February sit-in at the Woolworths lunch counter were released after 49 days in jail. The judge had originally ordered that the 11 originally arrested and convicted could pay a $300 fine or serve a 60-day sentence. Eight chose to stage a “jail-in” and started their sentence on March 18th. Over time, three left to file appeals, leaving sisters Patricia and Priscilla Stephens, siblings John and Barbara Broxton, and William Larkins behind bars. By the end of 49 days, those five were released early for good behavior. Patricia later wrote in her book, “Freedom in the Family,” that the Tallahassee black community threw them “a hero’s welcome” rally. All five protestors had been students at Florida A & M University, but because they had missed so many classes while in jail, they were asked to withdraw and re-enroll in the fall.

A few days later after their release, headed out on a CORE-sponsored Publicity Tour to talk about their Civil Rights experiences. The jail-in participants spent the rest of the summer traveling around the country. All continued to fight for equal rights in the years ahead.

May 8, 1945

Victory in Europe, Changes at Home

On May 8th, 1945, Victory in Europe (VE Day) was declared during World War II. Within a few months, the United States would drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan leading to the declaration of Victory in Japan (VJ Day).

The returning American soldiers changed the country, Florida, and Tallahassee in many ways. One was in the high number of veterans entering local colleges on the GI Bill. That led to a restructuring of higher education in Florida. Initially, the Tallahassee Branch of the University of Florida (TBUF) was established at the Army base at Dale Mabry Army field. The male TBUF students took classes at Florida State College for Women. Later, FSCW was officially made co-educational and converted into Florida State University in 1947.

May 9, 1967

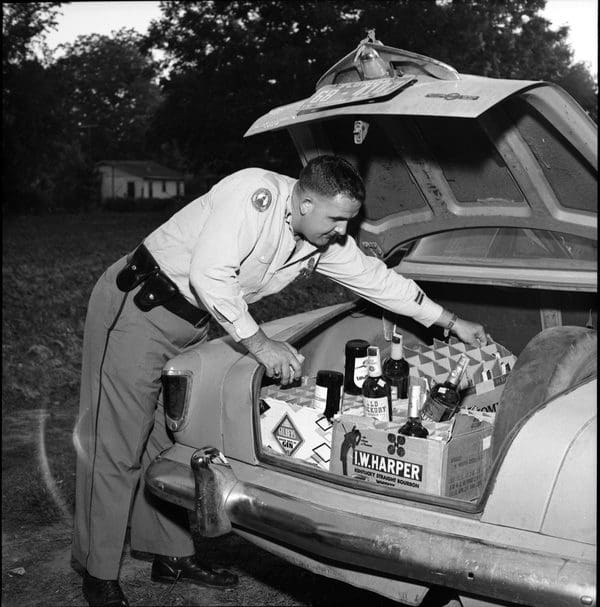

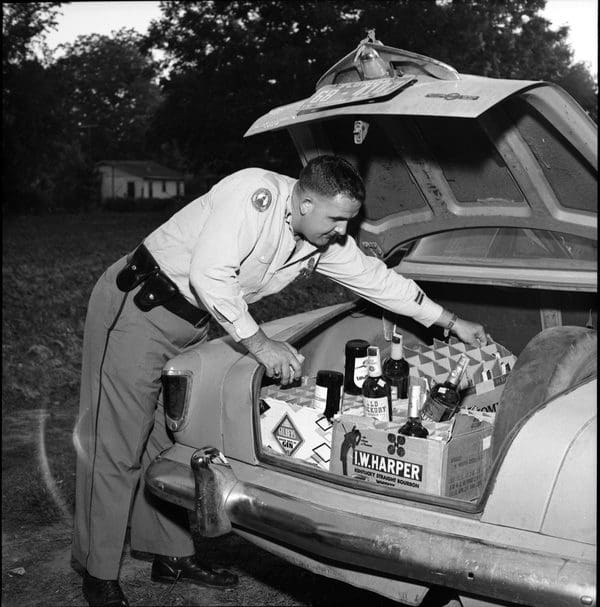

Prohibition in Leon County ends after 63 years

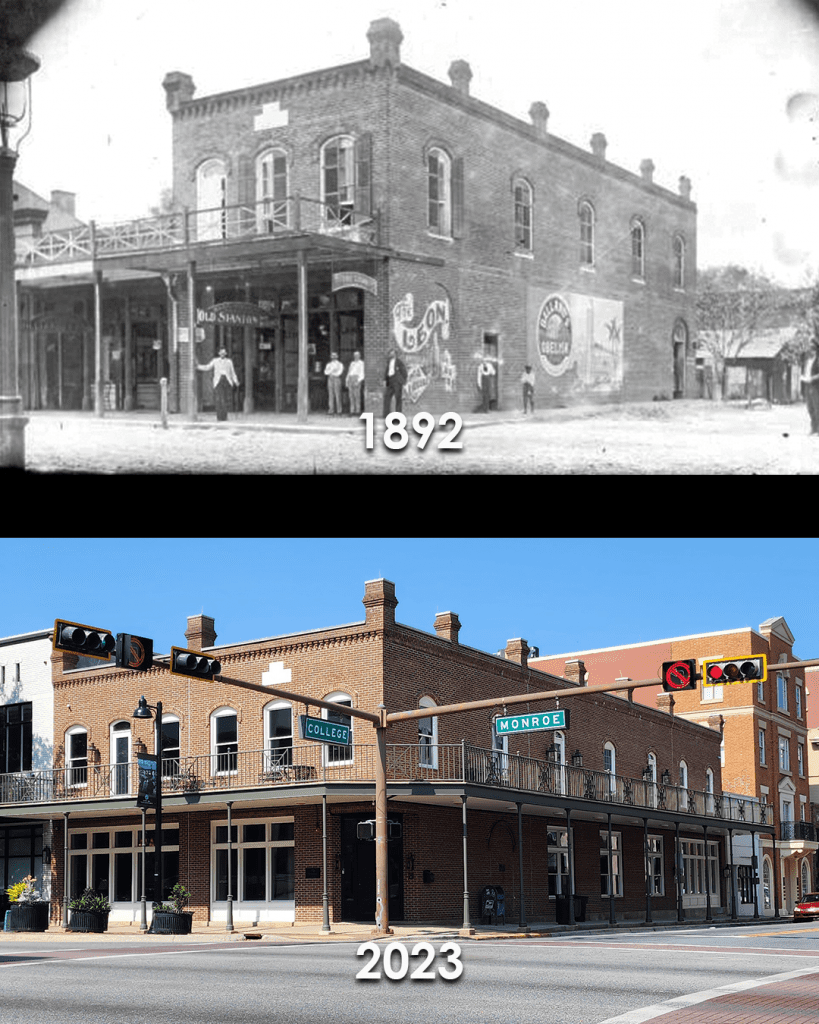

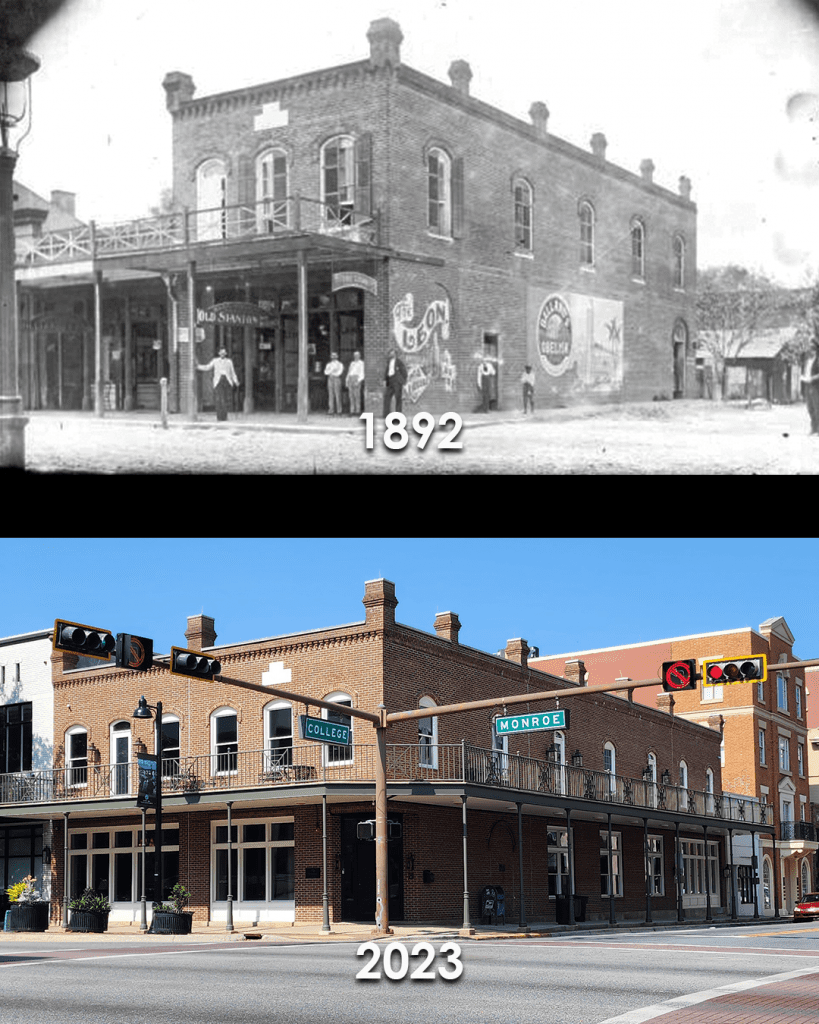

Prohibition across the nation lasted from 1920 to 1933, a total of 13 years. However, in Leon County, the flow of alcohol stopped in 1904 and didn’t start up again until May 9, 1967.

The work to turn the county “dry” began in the 1800s, but first, there was an effort to plant some very “wet” roots in the region. In the early years of settling the U.S. Florida Territory, one of the first and largest landowners in the Tallahassee area, the Marquis de Lafayette, encouraged the creation of vineyards. He wrote to friends in France and other European countries suggesting that they move to the area for the purpose of creating a region dedicated to growing French-style wine.

While his personal efforts to settle the region failed, others did follow through on the idea of growing grapes for wine in the area. One well-known Frenchman who dug into Lafayette’s idea was Emile Dubois. Dubois established the county’s first vineyards on his property where the Mission San Luis Living History Museum now sits and at another property near Lake Hall, part of present day Maclay Gardens State Park. By the 1890s Dubois was making thousands of gallons of wine a year.

It all changed for Dubois and the county on August 30, 1904. That was the day voters in Leon County voted 494 to 372 to prohibit the sale of alcohol and Dubois ended up moving his wine operation to New Jersey.

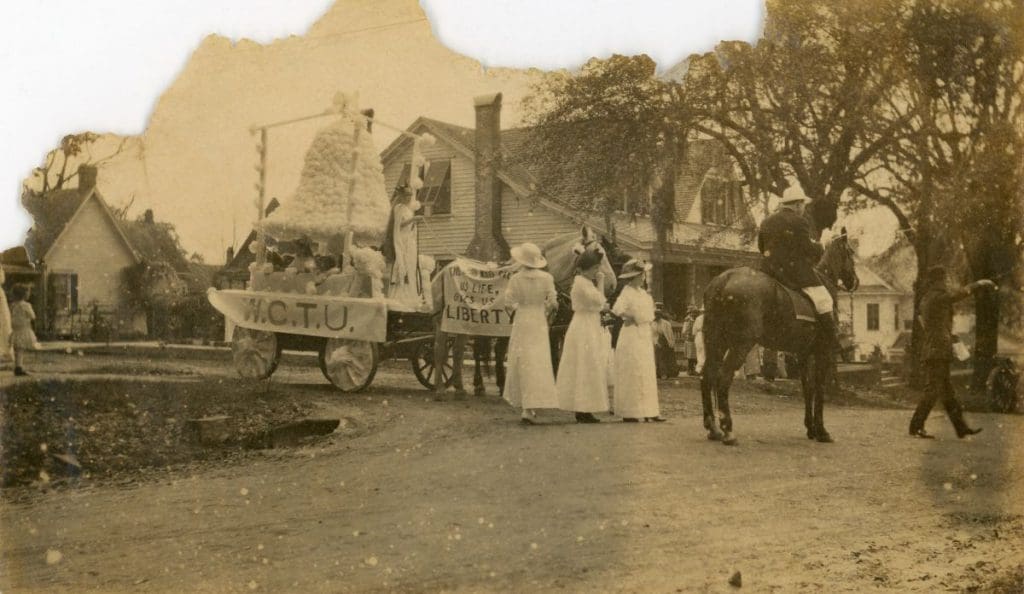

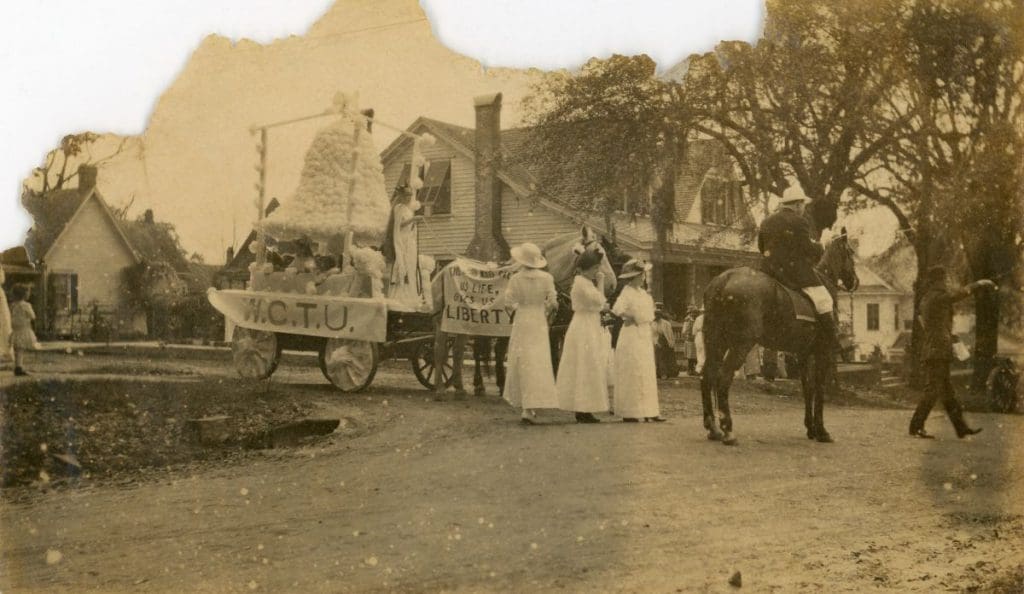

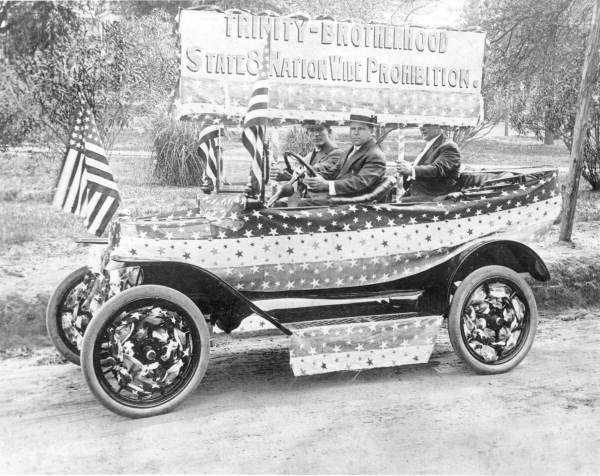

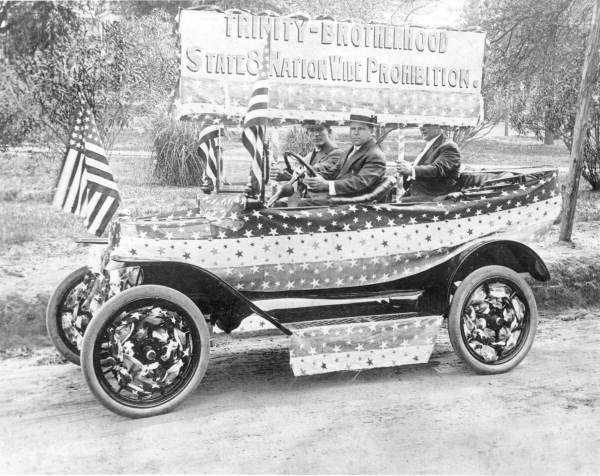

The issue of stopping the sale of alcohol had been growing over the years in the United States. In the 1800’s the idea that alcohol led to financial and moral problems in the home led to the creation of organized groups, mostly by women, demanding prohibition (and often the right to vote too). One of the first and largest organizations was the nationwide Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. As early as the 1870’s the group had influence in Tallahassee. A photo dated from that time of the group at a Tallahassee parade can be found in the State Archives of Florida. When the 1885 Florida Constitution made it possible for each county to individually decide this issue of alcohol sales and production, pressure increased.

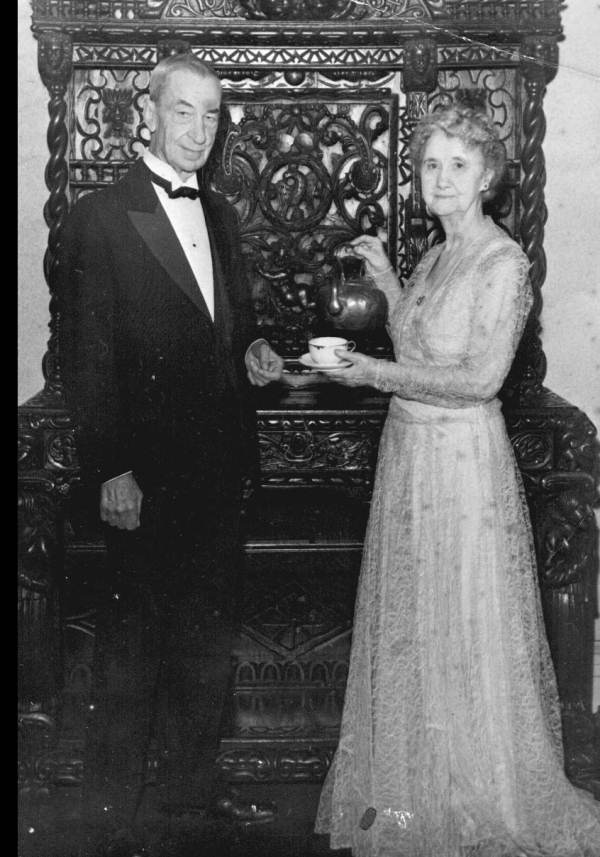

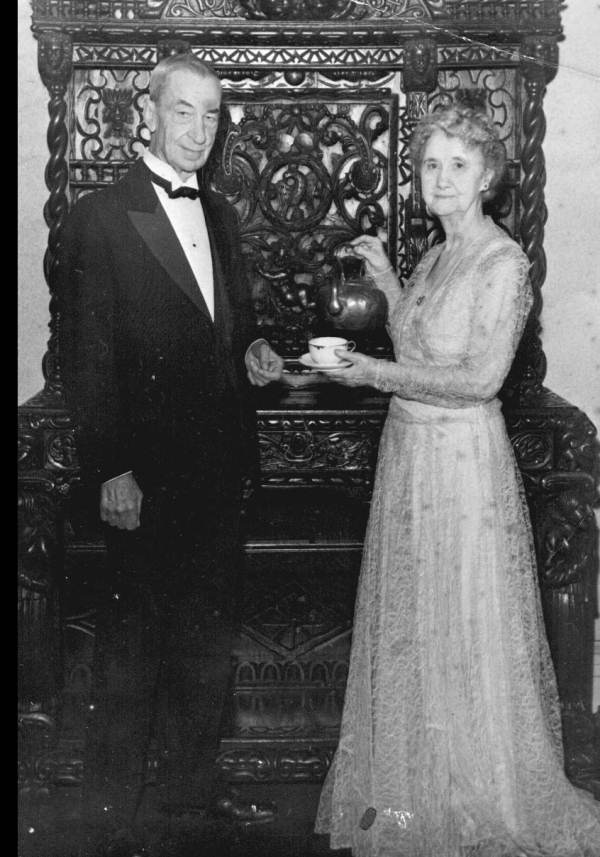

One of the leaders of the temperance movement in Tallahassee was Louella Knott. Louella was the wife of State Treasurer, William Knott, and together they were the future owners of what is now called the Knott House Museum. Moving to Tallahassee in 1897, Louella worked to organize the fight against alcohol in Tallahassee and Leon County. A men’s auxiliary group was created to join the fight in 1904 called the Leon County Local Option League and by the summer of that year, the issue was on the ballot and passed.

However, the now alcohol-free county wasn’t quite that dry. According to a Tallahassee Democrat article by Patrick Riordan in 1990, the Capital City “was wetter than the Gulf of Mexico.” While Dubois and his vineyard left the state and the city’s saloons closed, alcohol was also still sold legally in nearby Gadsden, Madison, and Franklin counties. Speakeasies and bootleggers within the county flourished. Lobbyists were encouraged to bring and conceal their own alcohol when they headed to the capital for the legislative session. It appears that it wasn’t until the national Prohibition of Alcohol and the accompanying Volstead Act that more enforcement tools were available in the county. Florida was the 15th state to ratify the 18th Amendment and on January 16, 1920, the amendment ushered in the Prohibition Era for the rest of the country.

There were arrests and there were raids over the next 13 years, but the alcohol kept flowing in the dry county. There were still local speakeasies (called “blind tigers”) and pharmacists realized they could legally sell items with alcohol in them for “medicinal purposes only”. Some local law enforcement also avoided the enforcement of the law.

When the Depression came, Florida became the 30th state to ratify the 21st Constitutional Amendment which officially ended the national prohibition on alcohol on December 5, 1933. While Leon County had voted in favor of that Amendment, it was still a dry county. Over and over again, the issue of wet v. dry came up in local elections with the sale of alcohol banned over and over again.

There were some wins. In May 1933, Leon County voters agreed to the sale of 3.2% beer. In June of 1960, voters agreed to allow liquor sales at package stores. However, a vote to approve liquor by the drink—the kind that could be sold in bars and restaurants—lost in that same election.

In April 1965, Luella Knott, who had continued to fight against the sale of alcohol over the decades, passed away. Three years later, on May 8, 1967, Leon County voted once again on the issue. Voters decided 12,187 to 6,277 to approve the sale of liquor by the drink which ended Leon County’s dry status.

May 10, 1865

Florida Surrenders

Confederate General Robert E. Lee may have signaled the end of the Civil War when he surrendered at the Courthouse at Appomattox in April 1865, but on May 10, 1865, Florida’s Confederate forces began their surrender in Tallahassee.

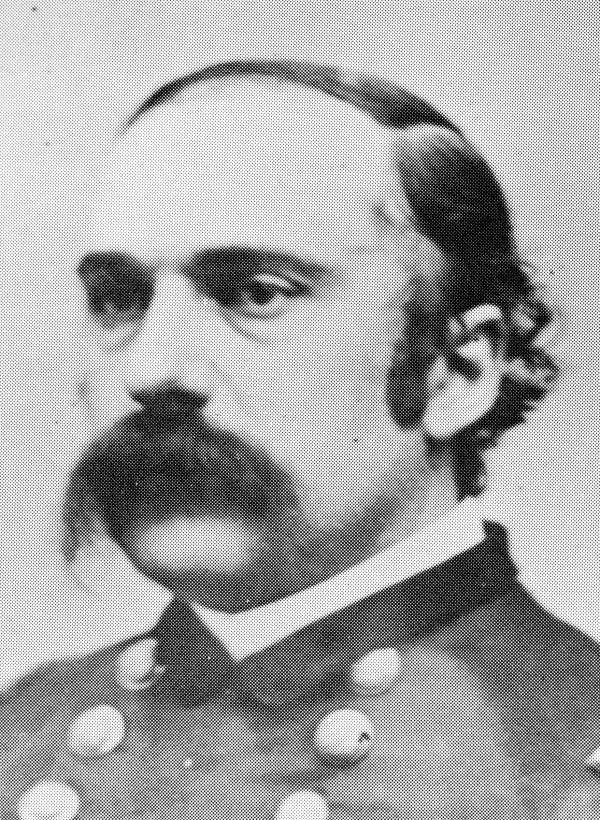

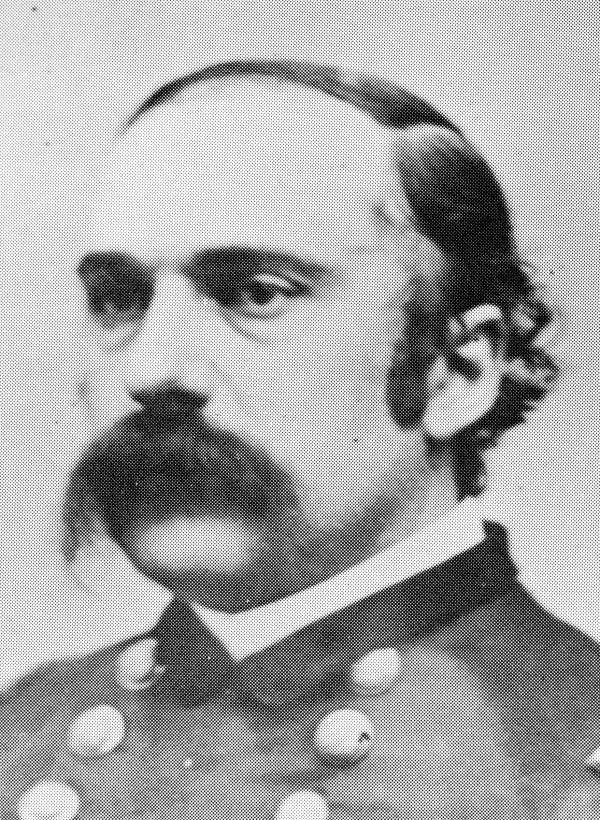

On this day, Union Brigadier General Edward McCook entered Tallahassee with a small band of 5 officers. He had left approximately 500 men from the Second Indiana Cavalry and Seventh Kentucky Cavalry four miles north of town on Thomasville Road while he went on the mission. Once in Tallahassee, McCook met with Confederate Major General Samuel Jones to accept the surrender of Florida’s Confederate Troops.

McCook settled into the Hagner House (later known as the Knott House) at the corner of Calhoun and Park Avenue and made that his temporary headquarters. His troops joined him in Tallahassee the next day. On May 12, the fort at St. Marks was officially surrendered to the Union as well. On May 20th, McCook read the Emancipation Proclamation on the steps of the Hagner House and held a ceremony officiating the transfer of power with the raising of the American Flag over the state capital building.

Tallahassee had been the only state capital in the south that had not fallen during the war. Earlier that year, Union troops had tried to take the city from the south. Marching up from the St. Marks lighthouse, the group was stopped by Confederate soldiers and students from West Florida Seminary at the Battle of Natural Bridge.

The acting Governor of Florida at the time of the May 10th surrender was Abraham Allison. He had taken over for Governor John Milton after Milton’s suicide on April 1st. According to the State Archives of Florida, Allison tried to go around McCook to work with Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson, to accelerate Florida’s return to the Union. A letter in the archive dated May 12th shows that Allison commissioned David Levy Yulee and four others (John Wayles Baker, Edward Curry Love, Mariano D. Papy, and James Lawrence George Baker) to meet with the President. Allison also called for a state legislative session on June 5th with a new election for governor on June 7th.

Allison’s actions came so quickly after the surrender that he angered many Unionists. McCook was ordered to not recognize any local or state government. On May 19th, Governor Allison resigned. On May 22nd, McCook placed the state under martial law. Union troops arrested Allison on June 19, 1865, and imprisoned him at Fort Pulaski with other Confederate officials for six months. President Johnson appointed William Marvin as the next Governor of the state on July 13, 1865.

Read more https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341933

Explore more about North Florida’s experiences in the Civil War by watching this episode of WFSU’s documentary series called Florida Footprints.

May 10, 1876

Lincoln Academy, Take 2!

On May 10, 1875, the second Lincoln Academy schoolhouse was dedicated at the corner of Park and Copeland streets.

The Freedman’s Bureaus established Lincoln Academy in 1869 to help educate formerly enslaved people from the area. The first building had four rooms and was located at Lafayette and Copeland Streets. The school burned down in January 1872. It took four years for this second building to be constructed on the same block. Later the State Normal School for Colored Students building was constructed next door. The book “African-American Education in Leon County, Florida: Emancipation through Desegregation”, by Debra Herman and Althemese Barnes says that Leon County was operating 51 schools by 1887. Twenty-nine of those schools were for black students and included Lincoln Academy.

After the Normal School was moved to the current Florida A & M University campus site in 1891, Lincoln Academy was renovated in 1897 and expanded to include the old Normal School building next door. According to the State Archives of Florida, at this point Lincoln Academy was teaching 450 students in 6 grades.

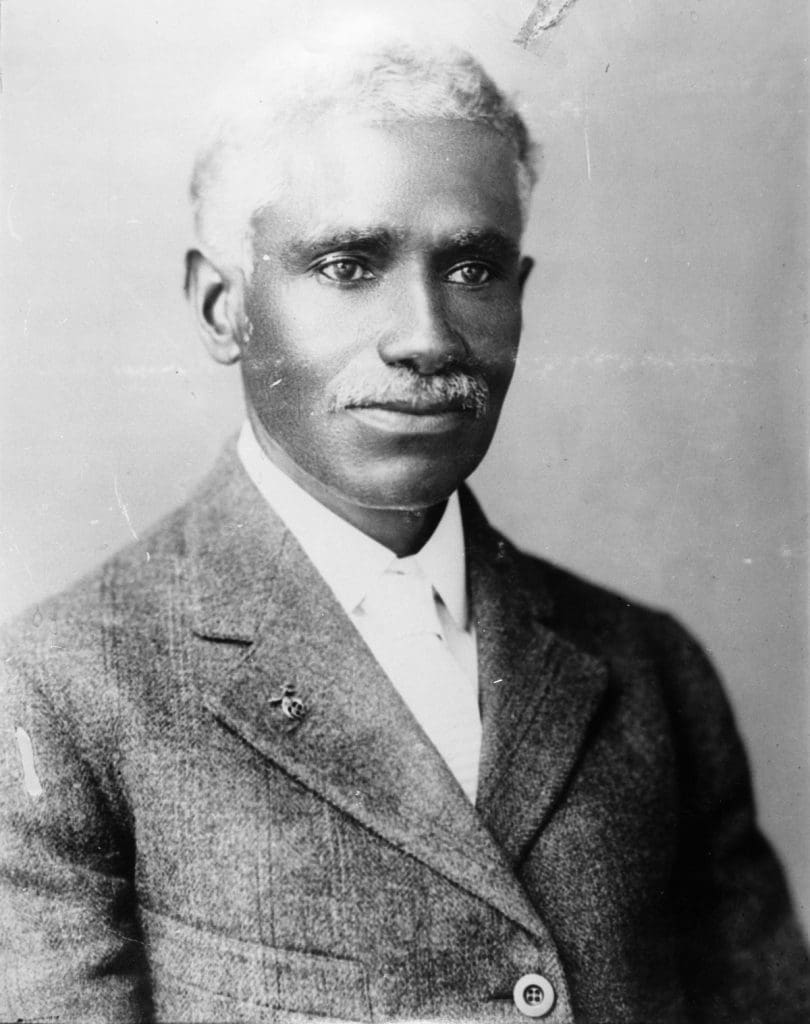

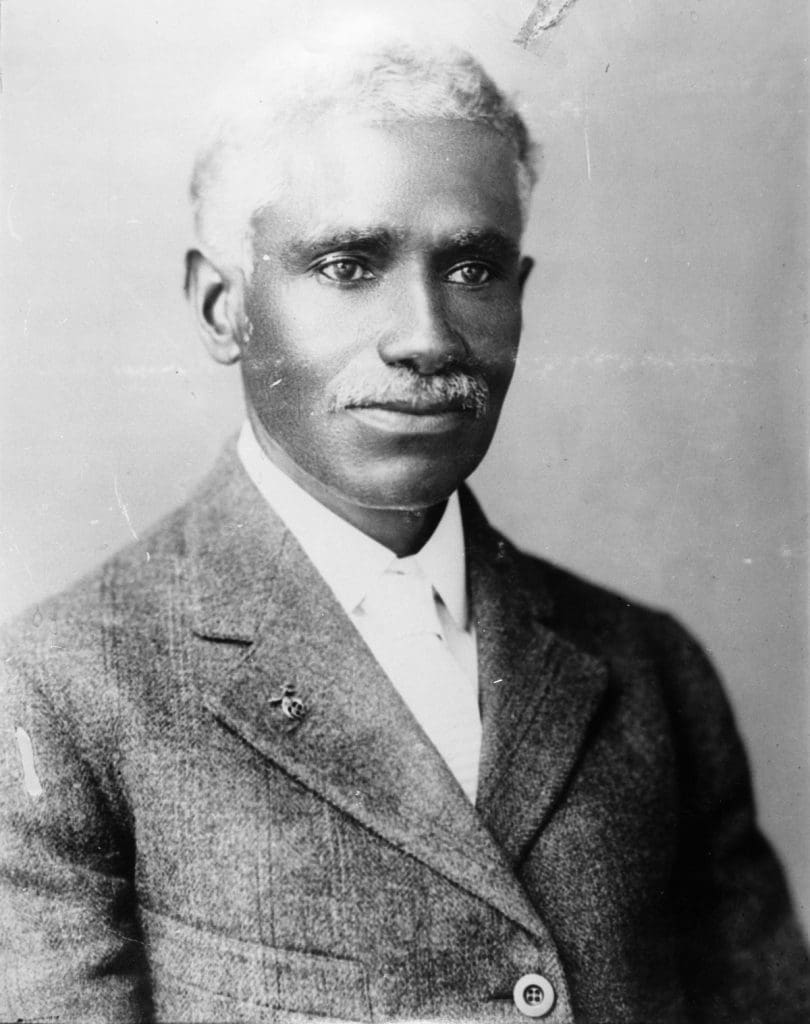

The first African American principal of the school was Tallahassee’s John Riley. Riley had been born in 1854 and was only 8 years old when the Emancipation Proclamation was read on the steps of the Knott house in Tallahassee. Riley taught himself to read and eventually became a teacher and then Assistant Principal of Lincoln Academy. He was the principal of Lincoln from 1892 to 1929.

Learn more about the life of John Riley and early African American education in this segment from WFSU’s Florida Footprints series.

In Leon County, Lincoln Academy used the Park and Copeland Street location until 1906 when a new wooden building was constructed on Brevard Street in Frenchtown. The Florida State College for Women took over the Copeland buildings as their own campus expanded. The old Lincoln Academy buildings housed music classes and a gymnasium for FSCW and later FSU. However, by 1965 both former Lincoln academy structures had been torn down for new construction.

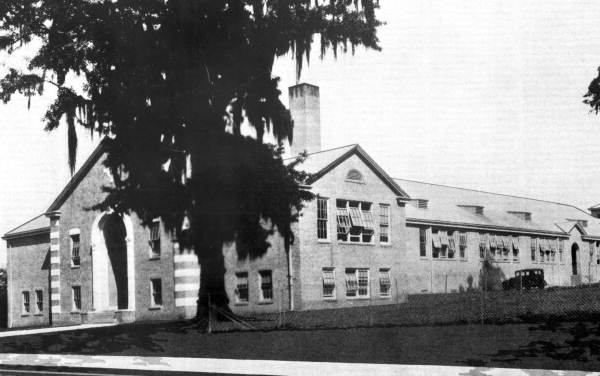

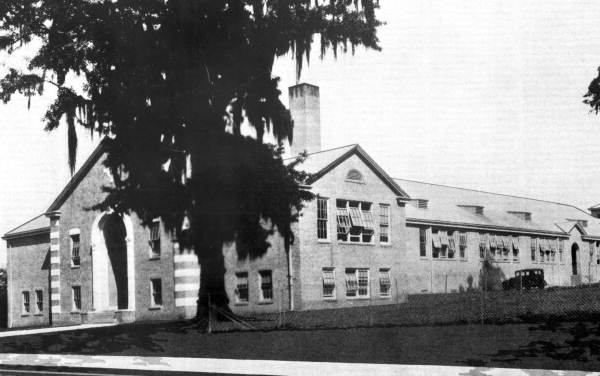

Meanwhile, the third Lincoln Academy in Frenchtown, which had been made out of wood, was replaced in 1929 with a two-story brick structure. By that point, the name had also been changed to Lincoln High School. The Brevard Street location continued to be used as a school for African Americans until 1968 when schools in Leon County were integrated and Lincoln was shut down. Other buildings on the campus housed other educational resources including the Alternate Learning Center which later became Sail High School. Structural issues forced the demolition of those external buildings in 2022. The 1929 brick structure is still used as a community center today.

May 13, 1936

Happy Birthday to the Apalachicola National Forest

On May 13, 1936, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Proclamation 2169 which turned Florida lands purchased by the Federal Government into the Apalachicola National Forest, The U.S. Government started buying the land from private landowners in 1933. It had accumulated 269,000 acres when it became a National Forest. The website for the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture says the ANF is “one of the most biodiverse forests in the country” and covers about 574,000 acres.

Since he had taken office in 1933, Roosevelt had focused on the care and improvement of the National Forests as a way to put young men back to work during the Depression under the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC. In March 1935, two National Forestry headquarters in Florida (Pensacola and Lake City) were consolidated and relocated to the more centrally located Tallahassee to save money.

Read the Proclamation 2169 for yourself here.

WFSU’s Ecology Producer Rob Diaz de Villegas has spent a lot of time in the Apalachicola National Forest. Explore his stories on the ANF here.

May 13, 1941

A man in Quincy is lynched twice.

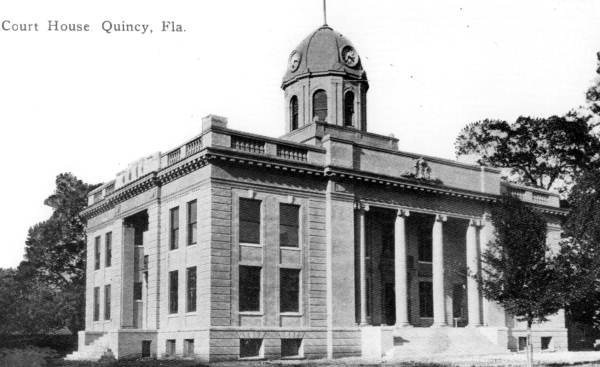

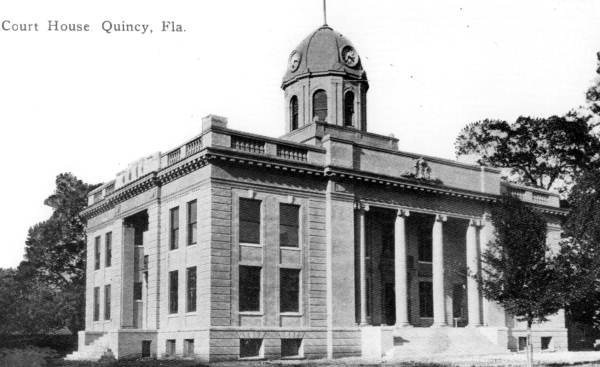

On May 13, 1941, a black man named A.C. Williams was murdered after being lynched for the second time in Quincy, Florida. Williams had been accused of robbery and sexually assaulting a white 12-year-old girl. Gadsden County Sheriff’s officers arrested Williams, but a group of masked men kidnapped him from jail. He was shot several times, beaten, and hung from a tree. Williams managed to survive and escape. Officers later found Williams alive but badly in need of medical help. On the way to the closest hospital for African Americans in the area, the FAMU hospital in Tallahassee, the car Williams was traveling in was stopped by a gang of masked men. Williams was kidnapped again. His body was found the morning of May 13 on a bridge north of Quincy. No one was ever arrested for either attack or the murder.

May 15, 1947

FSCW becomes FSU

On May 15, 1947, Florida State College for Women became Florida State University, ending 42 years of single-sex education at the school.

Florida State College for Women (FSCW) had accepted only females since 1905 when the Florida Legislature passed the Buckman Act. The Act consolidated and reorganized all of the higher education institutions in Florida under one umbrella that would be governed by the Florida Board of Control. Among the reorganizational decisions, the former coeducational Florida State College was converted into FSCW serving only white women in Tallahassee (originally called Florida Female College). The Buckman Act had also consolidated several schools into what became the University of Florida at Gainesville. UF was structured as an educational institution for only white men. Florida A & M University (as the State Normal and Industrial College for Colored Students) in Tallahassee continued to serve black men and women under the bill.

Learn more about the Buckman Act in this segment from Florida Footprints: A State of Change

FSCW grew over the next 4 decades. But the end of World War II changed it in a completely different way when high numbers of returning servicemen flooded colleges all over the country. They attended under the GI Bill of Rights (shorted to GI Bill) and officially known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944. The goal of the GI Bill was to help ease the veterans out of the service and back into non-military life. There was money for college, unemployment insurance, and housing.

The influx of men attending the University of Florida reached critical numbers in the Fall of 1946. An Associate Press Reporter on September 3, 1946, said that UF had 8,200 men apply for 6000 spots. With 20 days until the start of the fall term, Florida Governor Millard Caldwell and his cabinet made an emergency decision to allow 500 to 1000 men to attend FSCW. They would be housed at Dale Mabry Field which had been a military base during the war.

That fall, the Tallahassee Branch of the University of Florida (TBUF) opened. Male students lived and attended some classes at Dale Mabry Field, while also attending classes on FSCW’s campus. FSCW purchased a car to transport instructors to and from the two campuses. The FSCW registrar’s office reported that fall there were 501 men taking classes at the school. Of that number, 410 were there under the GI Bill. Including the FSCW’s female students, there were now 3,496 people attending classes on FSCW’s campus.

The TBUF turned out to be a short-term solution. Even while the number of students accepted into UF increased that fall, thousands more veterans were expected to apply. Once the Legislature returned to session in 1947, a new restructuring of higher education occurred. On May 15, 1947, the Governor signed a bill into law that turned Florida State College for Women into the coeducational Florida State University. The University of Florida was also turned into a coeducational university too. With that change in the law, Florida became the last state in the south to return to coeducational state schools.

Explore more about how our community changed after World War II in the Florida Footprints episode “The Paths of Progress.”

May 18, 1953

Robinson-Trueblood Swimming Pool Dedicated

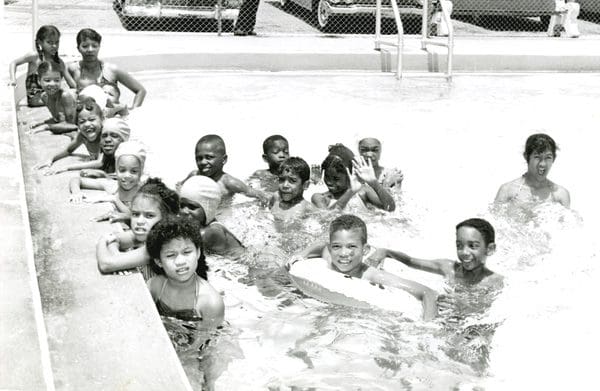

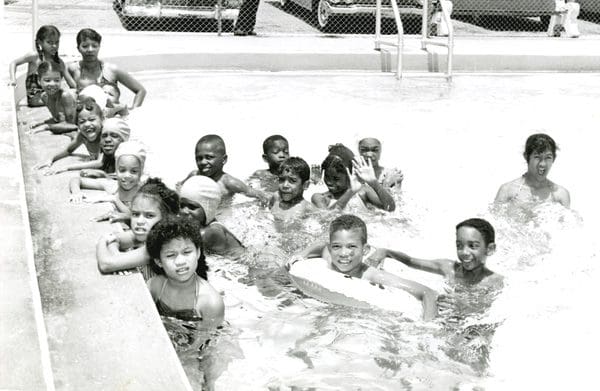

On May 18, 1953, the first Robinson-Trueblood swimming pool was dedicated in Tallahassee. The pool was the second municipal pool in the segregated city and the first one for African Americans in Tallahassee. The Tallahassee Democrat reported at the time that approximately 2000 people showed up for the ceremony which featured a combined band performance made up of students from local Lincoln, Griffin, and Lucy Moten schools. Plus, the Florida A & M Swim team held an exhibition in the new pool. The facility was named after two black soldiers from Leon County who were killed while serving during the Korean War: Pvt. Eddie Robinson and Cpl. David Trueblood.

The construction of the pool was part of a grand plan for the city. In 1952, the city decided to build Tallahassee’s first two public swimming pools. One for whites and one for blacks. They later decided to add a third pool, also for whites. The pools for whites ended up in Myers Park and Levy Park, and the pool for blacks was placed off Dade Street at the border between Frenchtown and Griffin Heights neighborhoods. The Robinson-Trueblood pool had a swimming team, taught swimming lessons, and trained lifeguards. For years, it was the place to be during the summer for much of the black community.

In 1964, that changed when all three city pools were closed to avoid integration. On July 2, 1964, the Civil Rights Act was signed into law. It prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Two days later, a group of young black swimmers in Tallahassee held a “wade-in” at the whites-only Levy Park pool. “Wade-in” and “swim-in” Civil Rights protests had been happening for years at segregated beaches and pools around the country, including Biloxi and St. Augustine. When the Independence Day “wade-in” happened in Tallahassee, the City Commission ordered that all three pools be closed.

Tallahassee’s Civil Rights Leader and President of the local NAACP, C.K. Steele, filed a lawsuit to reopen the pool but lost the case. The argument was that it wasn’t discrimination because all three pools received equal treatment. All three pools ended up staying closed for several years. One of the official arguments against reopening them became the cost of repairing and operating the pools.

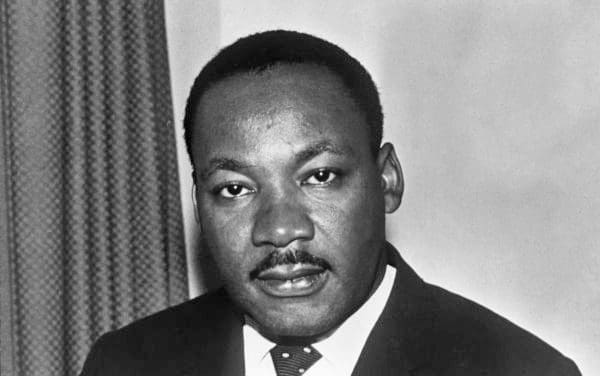

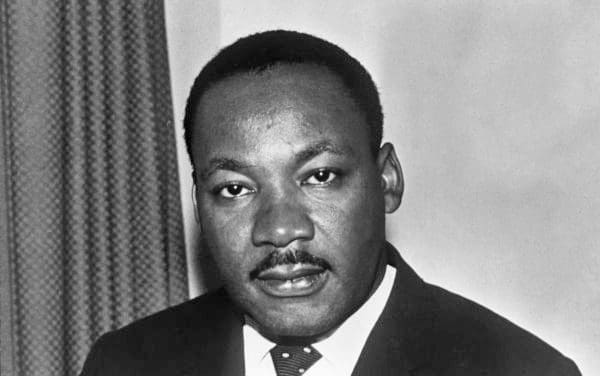

The fate of the pools changed shortly after the death of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. MLK’s assassination set off riots in Tallahassee as well as other parts of the country. Five days later, on April 9, 1968, the city voted to spend the money to repair and reopen the pools on May 1st. Still, it wasn’t until 2 years later that the segregation of the pools ended.

In 2000, the rectangular Robinson-Trueblood swimming pool was torn down and redesigned. The new facility dedicated in 2001 featured a pool with a waterslide, rain umbrella, and lap lanes.

Explore more about the Civil Rights Movement in Florida in the Florida Footprints episode “The Paths of Progress.”

May 20, 1834

The Marquis de Lafayette Passes Away

On May 20, 1834, America’s favorite fighting Frenchman, the Marquis de Lafayette, died in Paris, France. Born with the full name of Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, the Marquis was a French aristocrat who fought on the side of the Americans against the British during the American Revolution. Years later, as a thank you, the United States gave him given a large section of the newly acquired territory of Florida just north of Tallahassee. It was called the Lafayette Land Grant.

The land was bordered on the western side by today’s Meridian Road, stretched south to today’s Lafayette Street, and then east to just past Lake Lafayette. His eastern boundary then cut north through the present-day Vineyards subdivision on Mahan. It continued north to Roberts Road (one mile east of Centerville Road). The northern boundary then cut through the middle of the current Maclay Gardens, ending on North Meridian Road near the current Maclay School. Check out this map of the Lafayette Land Grant.

While the Marquis never saw the land he owned in person, he did try to settle the region. With visions of creating a land of vineyards and olive groves without slave labor, he encouraged a large group of French peasants to establish a colony on the shores of his land next to Lake Lafayette. That effort failed within a few months. The Marquis also encouraged an i#nflux of wealthier French and European men and women to move to the region. For example, French winemaker Emile Dubois established successful vineyards where Mission San Luis Museum sits today. It is believed that Frenchtown received its name from the large number of French immigrants who settled in that area.

Explore more about Lafayette’s influence on the region by clicking here.

May 20, 1865

Emancipation is Official in Florida

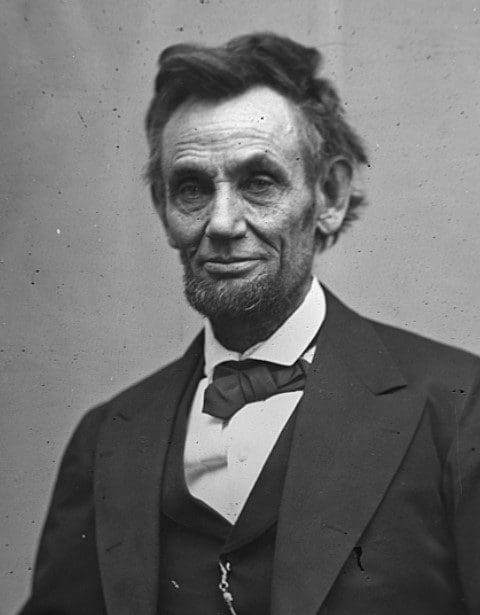

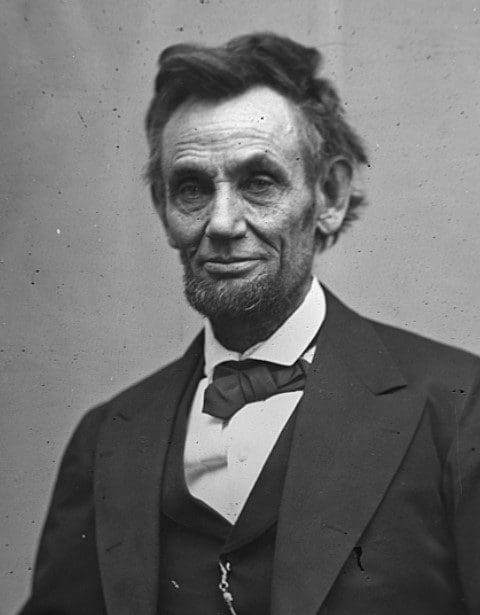

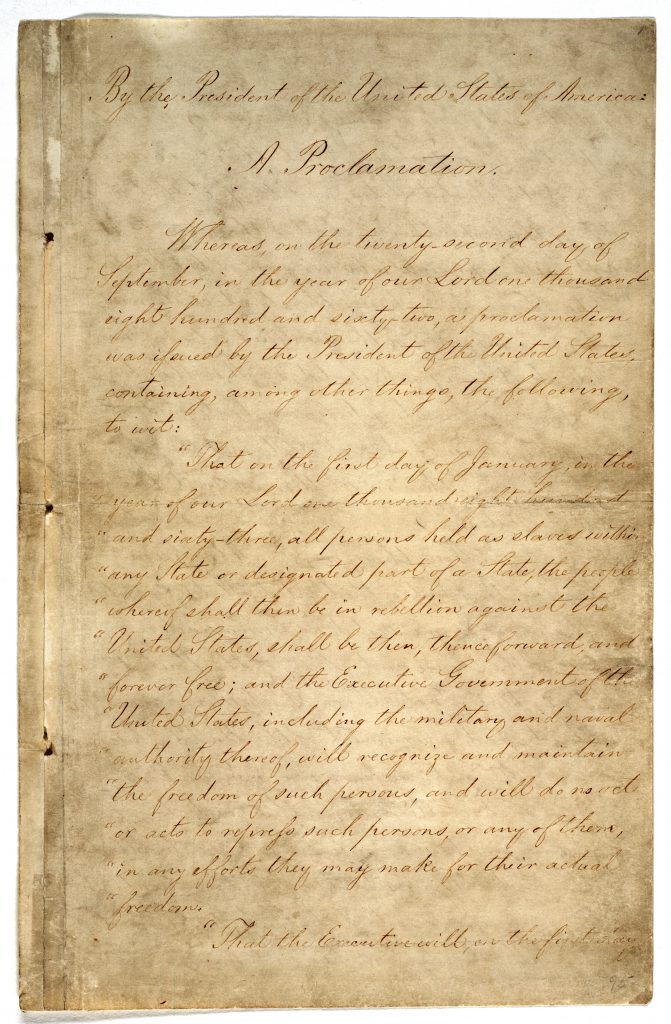

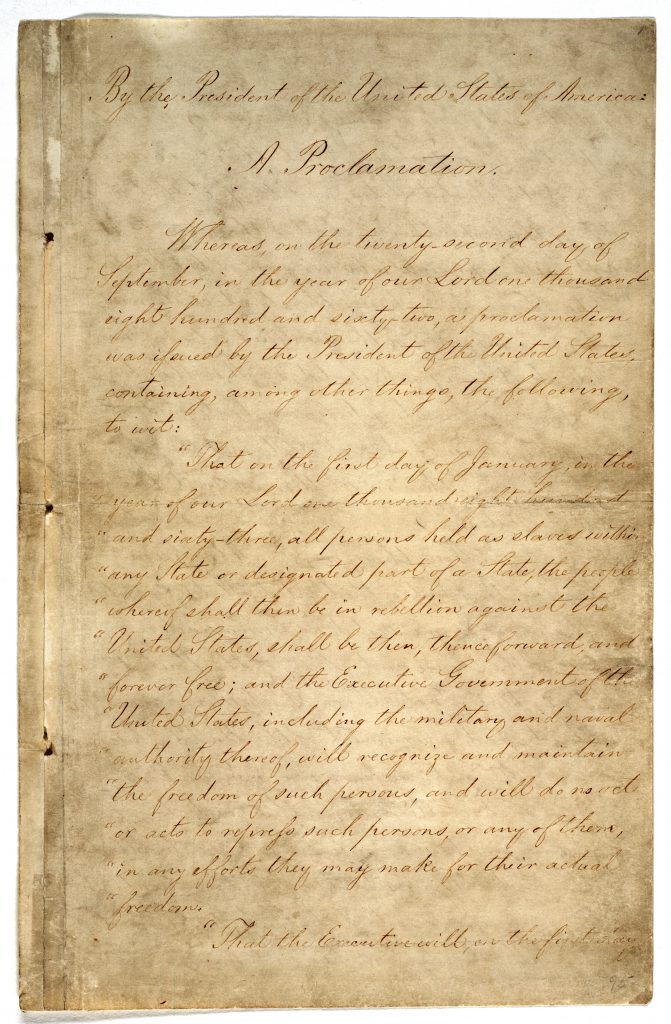

On May 20, 1865, Union Brigadier General Edward McCook read the Emancipation Proclamation on the steps of the current-day Knott house in Tallahassee. It was the first time the document freeing the enslaved people of Florida had been officially read in the state. More importantly, it was now recognized as something the people of Florida would be required to follow if they wanted to rejoin the Union.

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln had issued the proclamation two years earlier on January 1, 1863. It stated that all people enslaved in states that were in rebellion “are, and henceforward shall be free.” Florida had been one of those “rebellious states” since it had seceded from the Union on January 10, 1861. As part of the Confederacy, Florida did not recognize anything that Abraham Lincoln enacted during that time.

That all began to change in April 1865 when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia. Lee’s act essentially ended the war. On May 10th, Brigadier General McCook arrived in Tallahassee to accept the official surrender of the state. Ten days later, the transfer of power was complete and an American Flag flew once again over the state’s capital building. The time had come for Florida to accept the authority of the United States Government once again.

McCook had set up his headquarters in the home of Tallahassee’s Thomas Holmes Hagner. Built by George Proctor, one of the few free black men in the area before the war, today that building is known as the Knott House Museum. An article by the Tallahassee Historical Society says that on May 19th McCook sent officers to the homes and plantations throughout Leon County to give them a heads-up about the Proclamation. Then on the 20th, McCook stood in front of his headquarters and shared the contents of the Emancipation Proclamation. Ellen Call Long, daughter of former Governor Richard Call, witnessed the event. She wrote in her book “Florida Breezes” that the military fired two-hundred guns in celebration.

While May 20, 1865, is the day the enslaved people of Florida were officially freed, in Texas that day came on June 19, 1865. Texas was the last Confederate state to receive the Emancipation Proclamation freeing the enslaved people there. In 1866, African Americans in Texas, Florida, and other southern states began annual celebrations of their freedom. Over the years, many of the celebrations coalesced around the Texas date that had become known as “Juneteenth.” Even in Florida, the Florida Legislature recognized June 19th as “Juneteenth Day” in 1991 even though it did not make it an official holiday. In Tallahassee, the site of the first reading of the proclamation in Florida, the Emancipation Proclamation celebration date has remained on May 20. In 2020, the Tallahassee City Commission and Leon County Commission both made May 20th an official paid holiday for the city and county employees. In 2021, the U.S. Government made Juneteenth a Federal Holiday.

The Emancipation Proclamation

One additional aspect of the Emancipation Proclamation to note is that it only applied to Confederate states. Enslaved people in the border states that supported the North were not officially included in emancipation until the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865.

History is a work in progress, just like this page…

These are just some of the interesting facts about the history of our community. More moments, events, and people will be added to these memories as time goes on. The WFSU Local Routes team will continue to research, write, and add other historic moments to this month as time goes on. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for more new-to-you facts about the history of Tallahassee as well as our other north Florida and south Georgia communities. You can also share local historic moments you’d like to see included in our list. Email localroutes@wfsu.org.

Suzanne Smith is Executive Producer for Television at WFSU Public Media. She oversees the production of local programs at WFSU, is host of WFSU Local Routes, and a regular content contributor.

Suzanne’s love for PBS began early with programs like Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and continues to this day. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri with minors in political science and history. She also received a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of Florida.

Suzanne spent many years working in commercial news as Producer and Executive Producer in cities throughout the country before coming to WFSU in 2003. She is a past chair of the National Educational Telecommunications Association’s Content Peer Learning Community and a member of Public Media Women in Leadership organization.

In her free time, Suzanne enjoys spending time with family, reading, watching television, and exploring our community.