(Original Posted April 1, 2023)

April 1, 1818

Andrew Jackson burns Seminole village at Lake Miccosukee.

On this day, the First Seminole War arrived on the shores of Lake Miccosukee, located between the present-day Leon and Jefferson County lines. The roots of the war were planted during a series of attacks between U.S. Troops and a Creek tribe in southern Georgia culminating in a massacre of U.S. Soldiers at Fort Scott. The U.S. government ordered General Andrew Jackson, future American President and hero of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, to stop the Native Americans in 1817.

In March of 1818, Jackson pursued Creek and Seminoles into Spanish-held Florida, destroying native villages along the way. On April 1, 1818, Jackson and 3000 soldiers made their way toward the western side of Lake Miccosukee and what was one of the largest Seminole towns in the region. Aware of Jackson’s advance, the Native Americans in the town of Miccosukee evacuated the women, children, and elderly from the community while their warriors fought to delay the American soldiers. By the time Jackson arrived, most had escaped. Jackson’s troops rounded up the cattle and burned more than 300 homes, destroying the town. From there, Jackson and his troops continued the attacks as they headed south to the fort known as San Marcos de Apalache located in present-day St. Marks. This first Seminole War made possibly the Adams-Onis Treaty, which gave Florida to the United States. It did this by helping to demonstrate how little control Spain had over this territory.

You can also learn more about the ecology of Lake Miccosukee in this EcoAdventure from the WFSU’s Ecology Blog. Lake Miccosukee Sinkhole Hike: Floridan Aquifer Exposed!

April 1, 1865

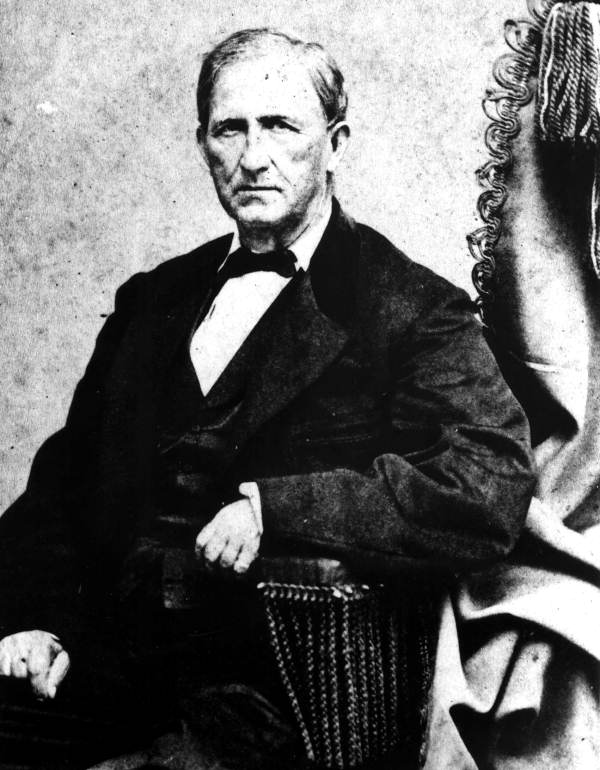

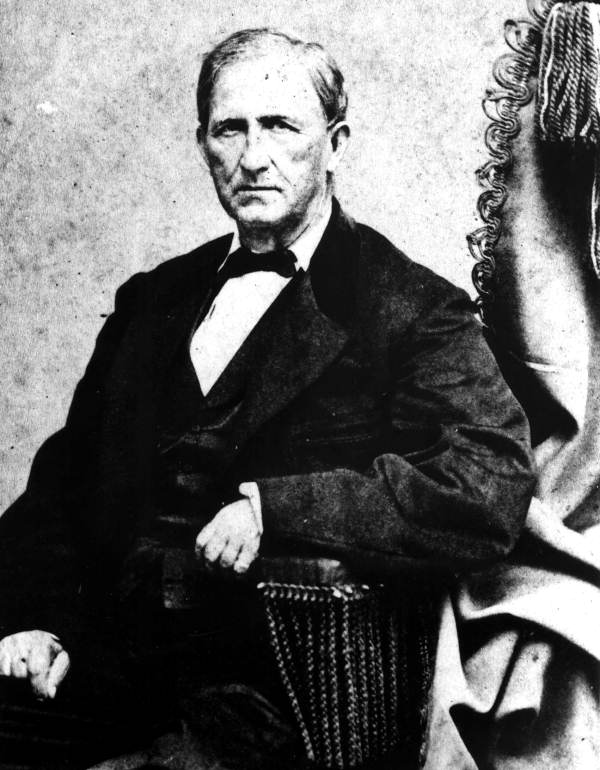

Florida’s Governor during Civil War takes his own life.

On this day, in the final weeks of the Civil war, Florida Governor John Milton committed suicide at his home near Marianna, Florida. Born in Georgia, Milton had also lived in Alabama and New Orleans before settling in Florida in either 1845 or 1846. In a South Florida Sun-Sentinel article from 1989, it is reported that Milton eventually had a plantation of more than 7,000 acres near Marianna with as many as 52 slaves before he entered politics. A secessionist, Milton won the Governorship of Florida in the October 1860 election. By the time he took office in 1861, Florida had left the Union and the Civil War was well underway.

Milton spent most of the war as Florida’s Governor in support of the Confederacy. At the same time, Union troops held major Florida cities like Pensacola, Jacksonville, and St. Augustine and attempted to blockade the waters off Florida’s coastline. Only a few battles were fought in the state. Including an important battle in March 1865. Union troops tried to capture Tallahassee in by attacking from the south. The Battle of Nature Bridge ended in a victory for Confederate troops and Tallahassee became the only Confederate state capital that was not captured during the war.

Despite the win at Natural Bridge, Milton saw that the end of the war was in sight and worried about what a Union victory would mean for the state. In his final message to the state legislature, he said that those from the north “have developed a character so odious that death would be preferable to reunion with them.”

On April 1, 1865, Milton, his wife, and his son returned to their home in Marianna from Tallahassee. Reportedly, Milton went immediately to his room and shot himself in the head. Milton was buried in Marianna’s Saint Luke’s Episcopal Cemetery.

Abraham Allison, the President of the Florida Senate, took over as Governor after Milton’s death. Serving about 7 weeks, Allison resigned in May when Union Troops took over the capital city. He was later arrested by U.S. authorities in June 1865 and spent 6 months imprisoned at Ft. Pulaski in Georgia with other Confederate officials.

Learn more about the Civil War in Florida by checking out Episode 3 of the Florida Footprints Documentary Series. That episode is called “The Confederate Road.”

April 1, 1907

April Fool’s Day Joke gone wrong

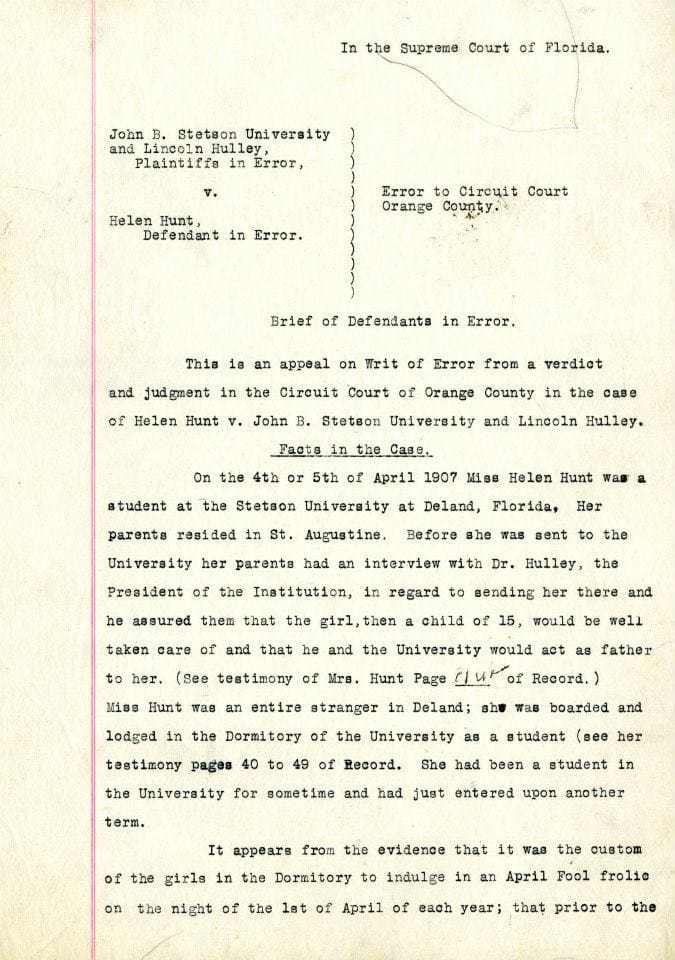

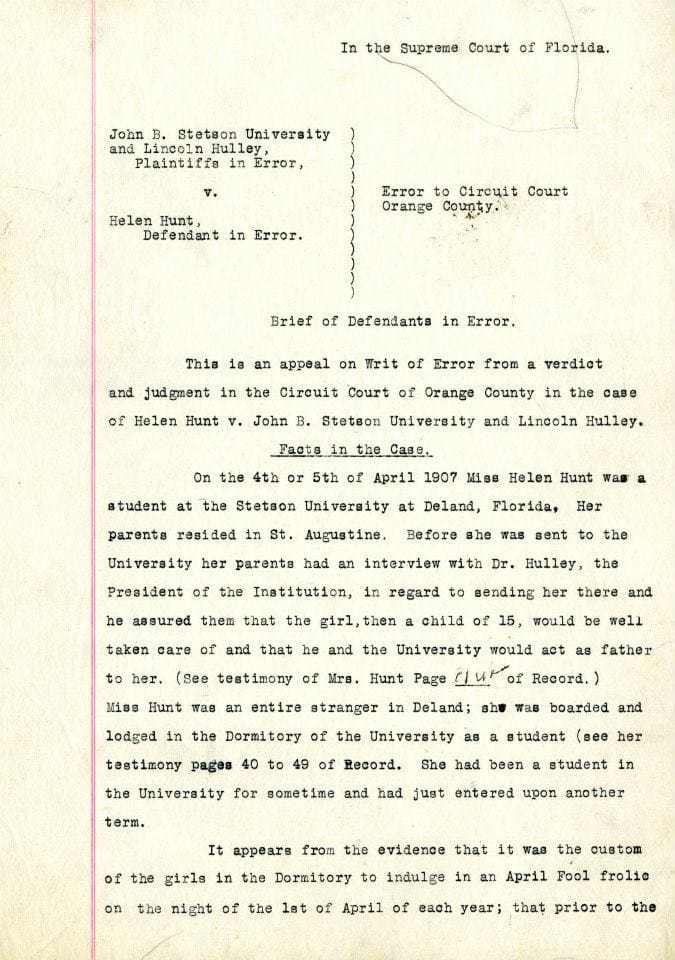

One of Florida’s most famous suffragettes, lawyer, and a graduate of Florida State College for Women in Tallahassee would never have attended the Tallahassee school if it hadn’t been for an April Fool’s Day prank.

Helen Hunt (later Helen Hunt West) from St. Augustine started off her secondary education at Stetson Academy in Deland, Florida. Apparently, “frolics” on April First were a tradition in Stetson’s dormitory for girls. In 1907, the practical jokers started it late at night by ringing cowbells to wake the other students. Court documents described the bells along with parading in the halls, “cutting the lights” and other events that “were subversive of the discipline and rules of the University. Some of the witnesses spoke of these disorders as bordering on insurrection.”

While the students may have considered the pranks as a “frolic,” Stetson’s President Dr. Lincoln Hulley declared the incident a “hazing” of the other students. Fifteen-year-old Helen, who had been one of the students initially awakened in the middle of the night by the bells, denied being involved in the hazing. However, under questioning did admit to eventually ringing one of the bells. She says the President immediately told her to pack her bags and leave town by nightfall. Several other students were disciplined, but all except Hunt were reinstated at the school. Within three weeks, Hunt was attending Florida Female College (later called FSCW) in Tallahassee to complete her coursework.

Hunt sued Stetson two separate times following the incident. The first time she sued for slander and libel saying her reputation had been threatened. While she won in the lower courts, the Florida Supreme Court reversed the ruling. In the second suit, Hunt said she was “maliciously, wantonly and without cause in bad faith expelled” from said University. She said that since she was still a child and the President (who had promised her parents that she would be looked after while at the school) intentionally failed to protect her. Hunt says the President did not let her parents know she had been expelled, did not make sure she had the funds to get home, and did not allow her to rebut the charges against her. While the trial court initially ruled in Hunt’s favorite, the Florida Supreme Court once again overturned that decision in 1924. The case was cited by colleges in other trials to support decisions regarding a college’s right to discipline students.

After Hunt finished her studies at Florida State College for Women, she wrote for the St. Augustine Record and later the Florida Times Union. She also studied law and in 1917 was one of the first women admitted to the Florida Bar. That same year, Hunt marched in front of the White House as a member of the National Women’s Party. Later Hunt worked with Suffragette leader Alice Paul to pass the 19th Amendment, focusing on efforts to get Florida to ratify the amendment. Even though that plan failed in Florida, enough states voted “yes” and the Amendment was added to the U.S. Constitution in August 1920. Hunt became the first woman registered to vote in Duval County and supported work to pass the Equal Rights Amendment.

Hunt married the city editor of the Florida Times-Union, Bryon West in 1927. She also ran for the U.S. Congress, but did not win. Helen Hunt West spent the rest of her life writing, speaking and continuing to work to get Florida to ratify the 19th Amendment. Florida finally approved it in 1969, 5 years after Hunt passed away.

Learn more about Helen Hunt West and other Women Lawyers in the Florida Bar book “Celebrating Florida’s First 150 Women Lawyers,” compiled & Edited by Wendy S. Loquasto.

April 2, 1513

Welcome to Florida!

Explorer and Conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon landed on Florida’s shores for the first time on April 2, 1513. He had set sail from Puerto Rico almost a month earlier with three ships. Ponce de Leon reportedly was searching for an island he had heard of, most likely Bimini, but the land he saw from the ship on Easter Sunday (March 27, 1513) was Florida. He continued to sail further north and, realizing that he was not looking at an island, landed near St. Augustine on April 2nd. Ponce de Leon claimed the land for Spain, naming it La Florida after Spain’s Easter celebration called La Pascua Florida which means “The Feast of Flowers.” Leon County in Florida is named after the explorer.

Learn more about the early years of expeditions and life in Florida by checking out the first episode in the WFSU Florida Footprint documentary series called “Once Upon Anhaica.”

April 3, 1965

Tallahassee’s William Knott passes away.

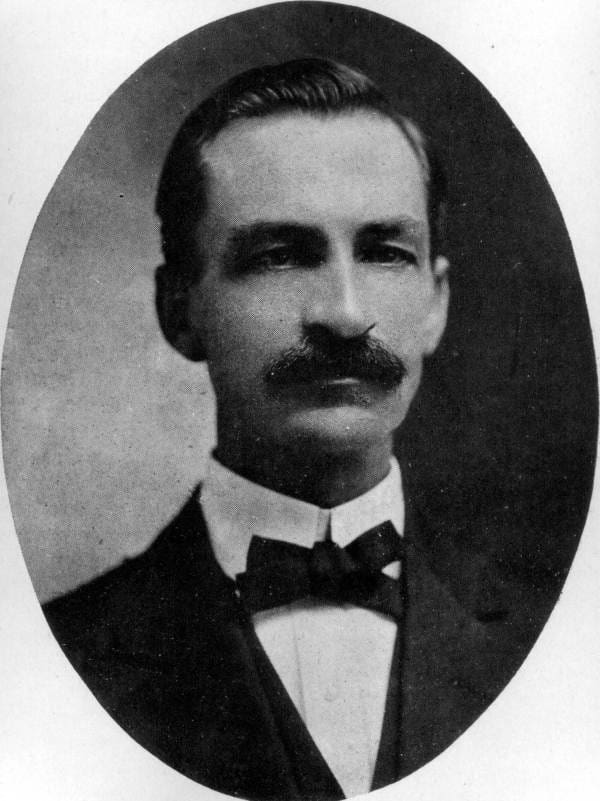

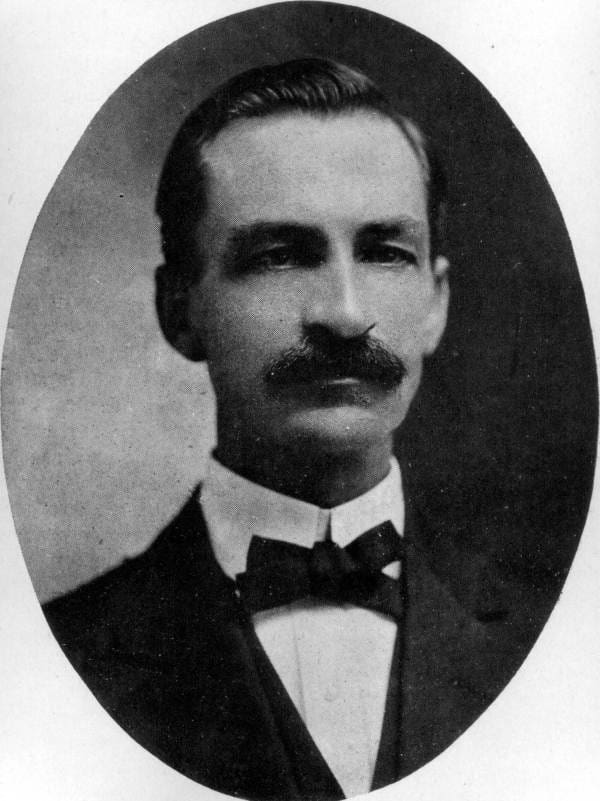

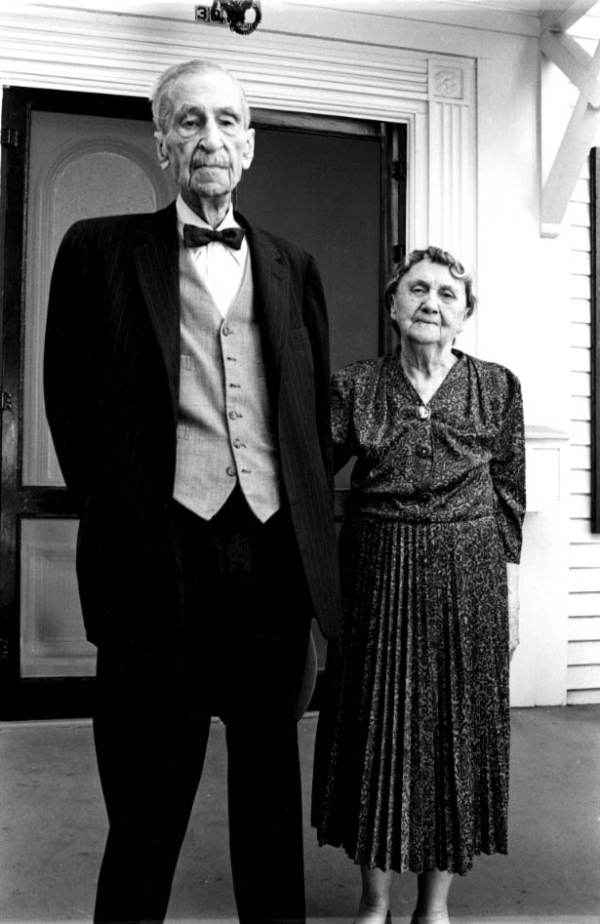

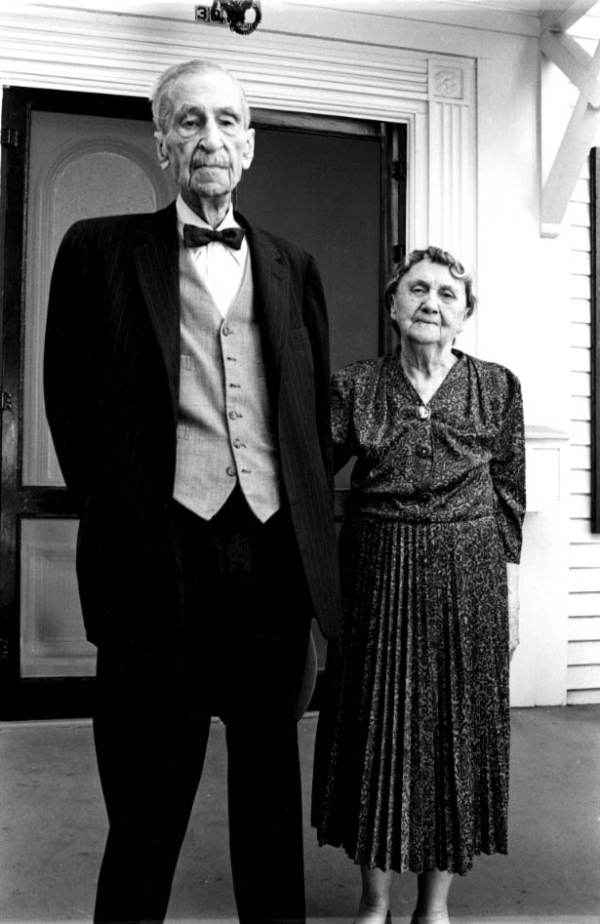

Former Florida State Treasurer William Valentine Knott died on this day in 1965.

Knott was born in Georgia in 1863 during the middle of the Civil War. When he passed away 101 years later, the country was in the middle of a race to reach the Moon.

At the age of 17, Knott traveled by wagon with his family to live in Leesburg, Florida. In 1895, he married Luella Pugh. Two years later, Knott and his bride moved to Tallahassee where he worked for the state.

Knott served twice as Florida State Treasurer. The first time from 1903 to 1912 and the second time from 1928 to 1941. In addition to his work as State Treasurer, he also served as the Superintendent of the Florida State Hospital in Chattahoochee from 1921-1927.

When he and Luella returned to Tallahassee from Chattahoochee, they bought the house on Park Avenue now known as the Knott House. In 1865, the home had been the site where the first official reading of the Emancipation Proclamation in the state took place.

After Knott’s death, his body lay in state at Florida’s capitol building. His wife, Luella, died eight days after him at the age of 93.

You can learn more about the William and Luella Knott and their famous home, by heading to the Knott House Museum website.

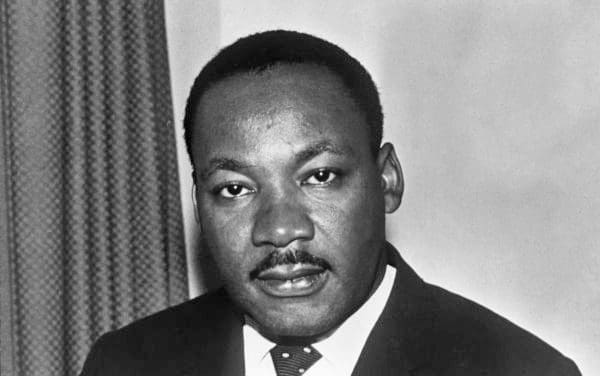

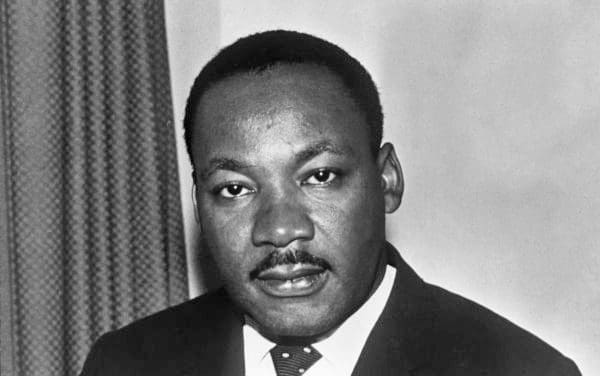

April 4, 1968

MLK Assassination and the Tallahassee Riots

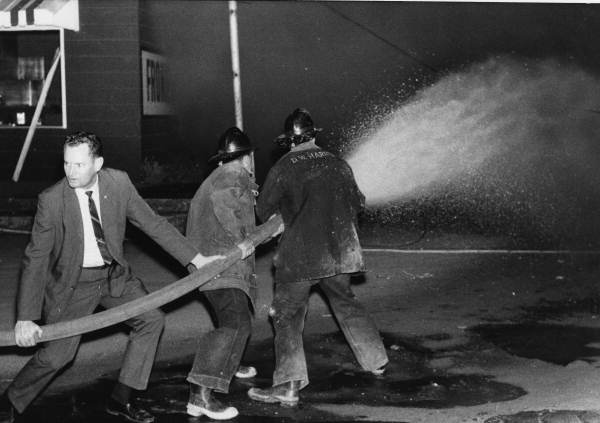

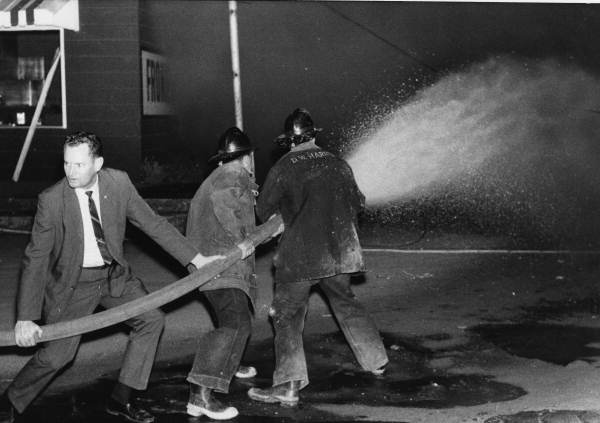

Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4th, 1968. Riots erupted in cities all over the United States, including Tallahassee. According to a 1984 article by Susan Hamburger for the Tallahassee Historical Society, the incidents in Tallahassee had begun in grief and with protests but quickly turned to anger and violence. An article called the “FAMU Way Historical Survey,” created by FAMU History professors for the City of Tallahassee, also included a section on the riots. They also said the transition from shock and sorrow on the FAMU campus turned to rage within hours.

It began with rioters targeting cars driving passed FAMU Campus with rocks and bottles. Then someone torched two trailers at Southern Mobile Home Brokers on South Monroe Street. As firefighters and police responded to the fire, rioters pelted them with bottles and bricks.

With orders to keep the FAMU students on campus, more than 150 police officers cordoned off the perimeter of the University. The violence escalated as “light-caliber” bullets and arrows were shot at police cars. Officers returned fire, reportedly with “warning shots” and also knocked out streetlamps to make it harder for the rioters to target them. Eventually, police fired tear gas at the students which ended the standoff.

But while the incidents on campus stopped for the night, that wasn’t the end of the violence. Crow’s Grocery Store on Lake Bradford Road was firebombed. The owners lived in an attached home and while most got out, one of the owner’s sons was trapped and died. Two local teenagers were later arrested and sentenced to life for the murder.

The next morning, Friday, April 5th, a memorial for King was held at Lee Hall. While the University President called for non-violence, there were vocal protests. The riots began again later that day. Two Frenchtown furniture stores, one on North Macomb street and One on West Fourth Street, were firebombed and a laundry mat on West Pershing Street was vandalized and looted. Violence escalated with more gunfire and FAMU President George Gore shut down the University for a week. By Sunday, April 7, the riots had ended.

Learn more about the riots and the aftermath in Tallahassee’s history by reading the “FAMU Way Historical Survey” by David H. Jackson, Reginald Ellis, Will Guzman, and Darius Young.

You can also check out the Tallahassee Historical Society article called “The 1968 Tallahassee Riots Following the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.” by Susan Hamburger.

April 6, 1899

Famous Apalachicola Botanist, and Author passes away.

Dr. Alvan Wentworth Chapman died on this day in 1899 in Apalachicola. He grew up in the northeastern part of the country but moved to Florida in 1835 to practice medicine. Chapman lived first in Quincy and then Marianna. The physician eventually moved to Apalachicola in 1847. After the Civil War he became internationally known for his work on the botany of the area. He wrote “Flora of the Southern United States” which was one of the first books about southern plants. The Chapman Botanical Gardens in Apalachicola is named after him as well as the “Chapman oak” and “Chapman’s rhododendron.”

Learn more about his life in this article by Dale Cox on his Explore Southern History website.

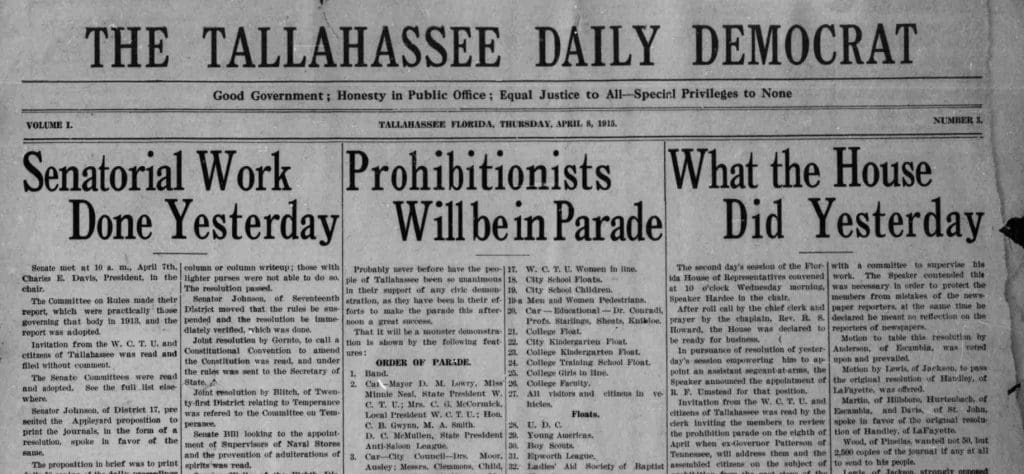

April 6, 1915

One step closer to becoming the Tallahassee Democrat

On this day, Tallahassee’s weekly newspaper officially became a daily paper. John G. Collins founded The Weekly True Democrat in 1905. He later sold it to Milton Asbury Smith. Smith adjusted the name and the publishing schedule several times over the years. During the legislative sessions in 1913 and 1915, he published daily. It reportedly officially became an afternoon daily paper at the end of the 1915 session. That year, the newspaper name morphed from the “Tallahassee Daily Democrat” to just “The Daily Democrat.” In 1949, under a different owner, the name was finally changed to the Tallahassee Democrat.

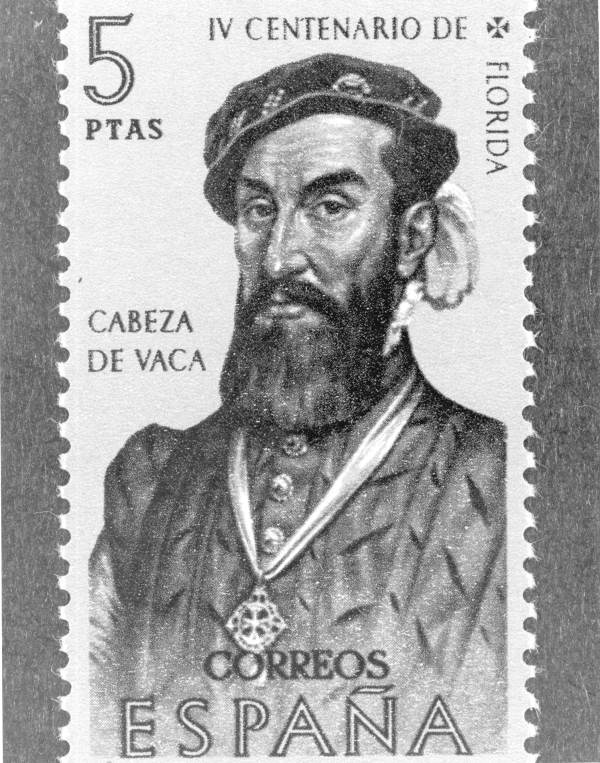

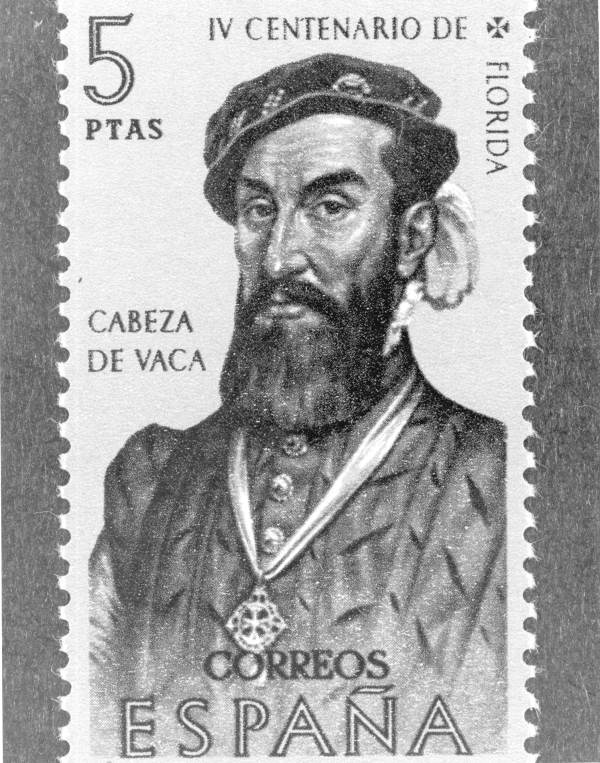

April 8, 1460

Happy Birthday to the guy who named Florida!

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon first landed on the shores of Florida in April of 1513, but on this day 53 years before that, he supposedly took his first breath on this day. We say “supposedly” because there are no baptism or other records proving that specific date. However, the information most accepted by scholars is that Ponce de Leon was born in Santervás de Campos in Spain in 1460 on this day.

Ponce de Leon first sailed to the New world as part of the second expedition of Christopher Columbus in 1493. He was later named Governor of Puerto Rico. Eventually he when on a quest to search for more lands for Spain. In 1513, he headed out with three ships for what some say was the island of Bimini. He ended up on the coast of Florida instead. After arriving on the shore near St. Augustine at Eastertime, he named the land in honor of Spain’s Pascua Florida celebration which means “Feast of Flowers.” He later died after he was injured on another expedition in 1521.

Learn more about the early years of expeditions and life in Florida by checking out the first episode in the WFSU Florida Footprint documentary series called “Once Upon Anhaica.”

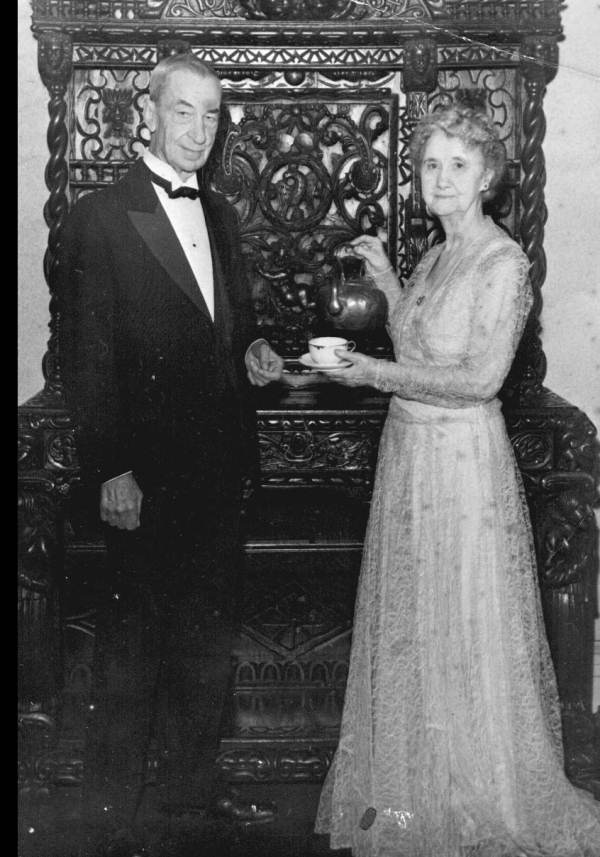

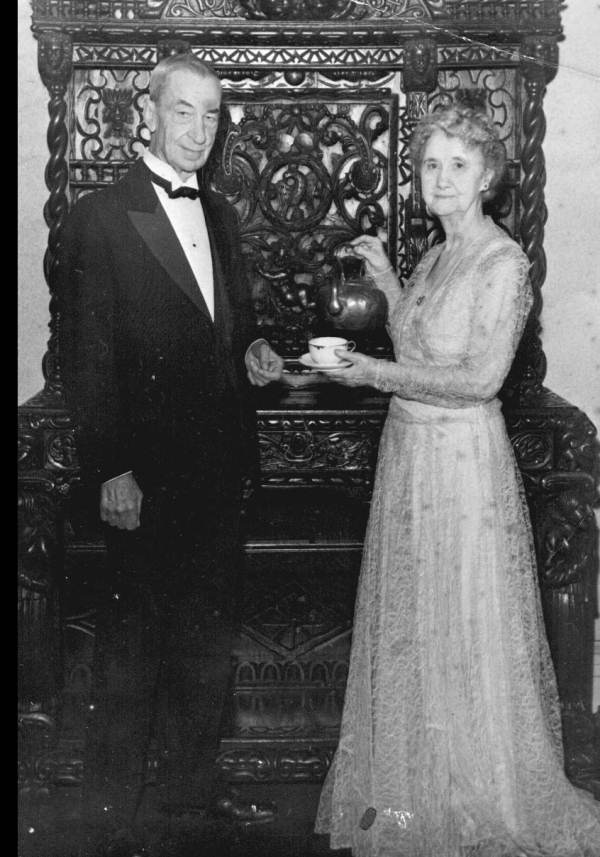

April 11, 1965

Tallahassee Poet, Author, and Artist who owned Knott House passes away

Tallahassee’s Luella Pugh Knott died on this day in 1965. Born in North Carolina in 1871, Knott taught school in central Florida where she met her future husband, William Valentine Knott. They married in 1895 and two years later they moved to Tallahassee so that William could work for the state. He eventually became the longest serving State Treasurer serving two stints in the position. Between those two time periods, the Knotts lived in Chattahoochee where William served as the administrator of the State Hospital.

When the couple returned to Tallahassee, they bought the historic home now named after them, the “Knott House.” The history of that house goes back to the Territorial days of Florida. In 1842, Attorney Thomas Hagner bought the land and had the house built there a year later, possibly by George Proctor, a free black builder in the area. After the Civil War, Edward McCook, a Brigadier General in the Union army, used the home as a temporary headquarters. McCook read the Emancipation Proclamation from the steps of the home on May 20th, 1865, in an event still celebrated in Tallahassee today with reenactments at the house.

When the Knotts bought the home, the couple added large columns to the front of the building and made it their own. Luella wrote poems that she tied to the furnishings with ribbons leading to the home’s nickname “the House that Rhymes.” The home is now owned by the Museum of Florida.

Luella Knott was heavily involved in social causes, specifically Tallahassee’s temperance movement. She was part of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and worked to convince the citizens of Leon County to outlaw the sale of alcohol in 1904, sixteen years before the 18th Amendment and Volstead Act brought prohibition to the rest of the nation. Alcohol wasn’t sold again in the county until 1960 and then only in liquor stores. The purchase of individual drinks was not allowed until 1967, two years after her death.

Luella Knott died at the age of 93. She passed away 8 days after her husband William, who passed away at the age of 101.

You can learn more about Luella and William Knott and their famous home, by heading to the Knott House Museum website. Included on the site is a poem that Luella wrote in the days after the death of her husband.

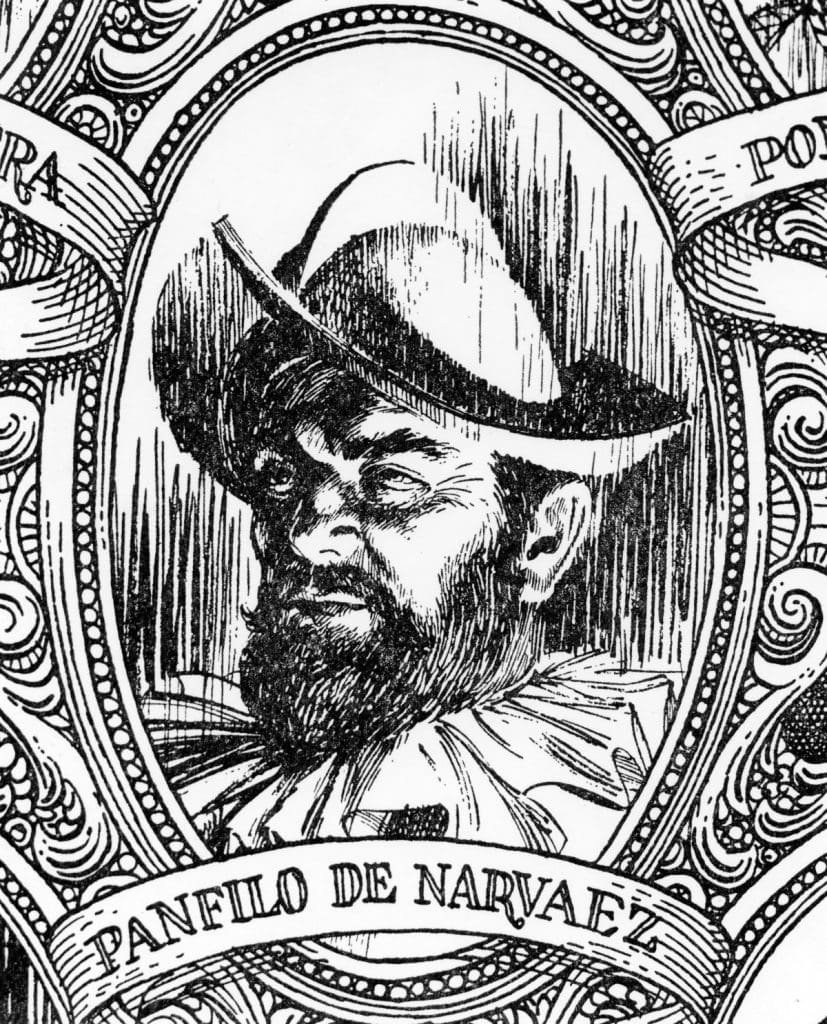

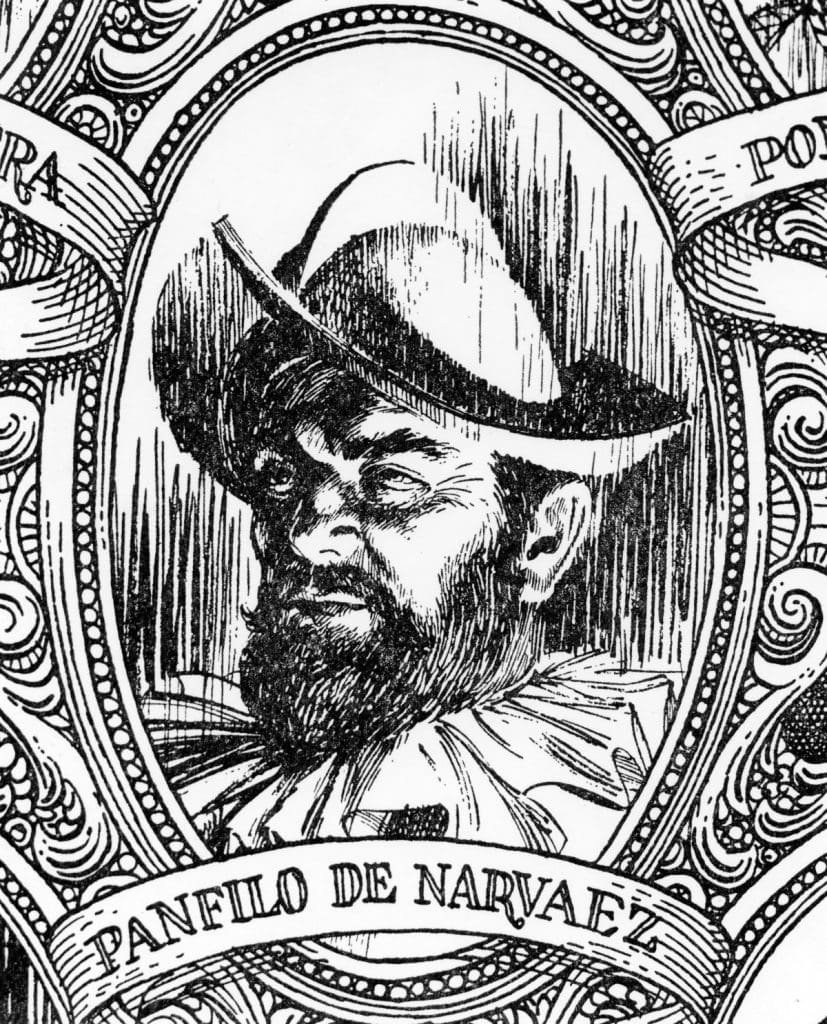

April 14, 1528

Disastrous Spanish Expedition in Florida Begins.

Spanish Explorer Pánfilo de Narváez and his crew landed near present day Tampa and St. Petersburg on this day in 1528.

Not long afterwards, Narváez and his men were the first documented Europeans to visit present day Tallahassee area. By all accounts, it failed horribly, starting with a series of really bad decisions. First Narváez split up his men, sending 100 by boat and 300 by land to the north. The boats never could find the soldiers who took to the land. Eventually, those boats headed to Mexico.

On June 25, 1528 Narváez arrived in present-day Tallahassee where a large population of Apalachee people were living. Narváez attacked what he thought was the Apalachee capital of 40 homes, but it turned out to be just a small village outside of the much larger community. Hundreds of Apalachee warriors retaliated, forcing Narváez and his men back toward the Gulf of Mexico.

The expedition ended up struggling for survival at the edge of what is now known as Apalachee bay. While they attempted to build boats to leave the area, the soldiers ate their horses for food. They called the bay the “Bahia de los Caballos” which means Bay of Horses. Just over 240 men were alive in September when five boats were ready to leave the Bay and head to Mexico. But storms, starvation, thirst, and disease reduced their ranks to 80 by the time they reached Texas. Narváez never even made it that far. He died when his boat was blown out to sea. The remaining members of the expedition didn’t have much better luck. By 1532, only 4 of the original crew were still alive. They wandered the region for years and did not find fellow Spaniards who could take them to Mexico City until 1536.

Learn more about the early years of expeditions and life in Florida by checking out the first episode in the WFSU Florida Footprint documentary series called “Once Upon Anhaica.”

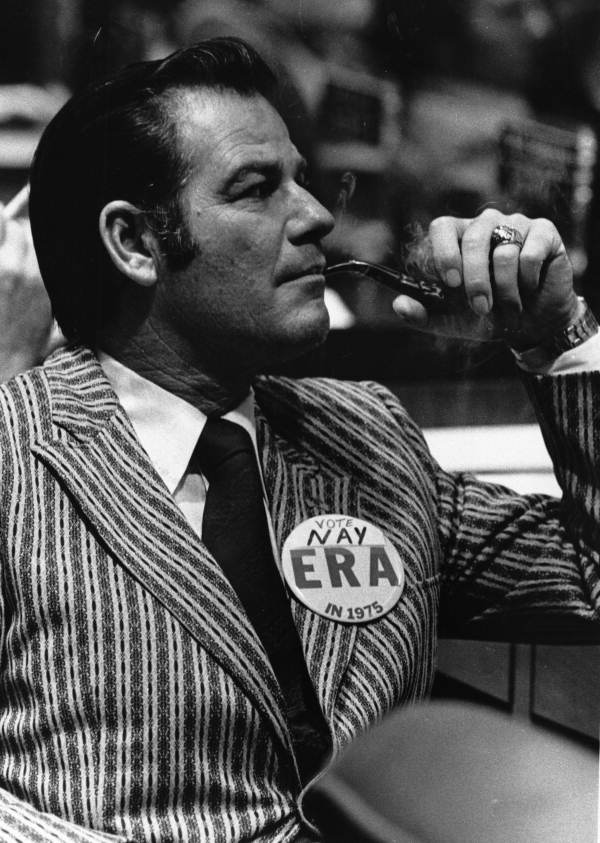

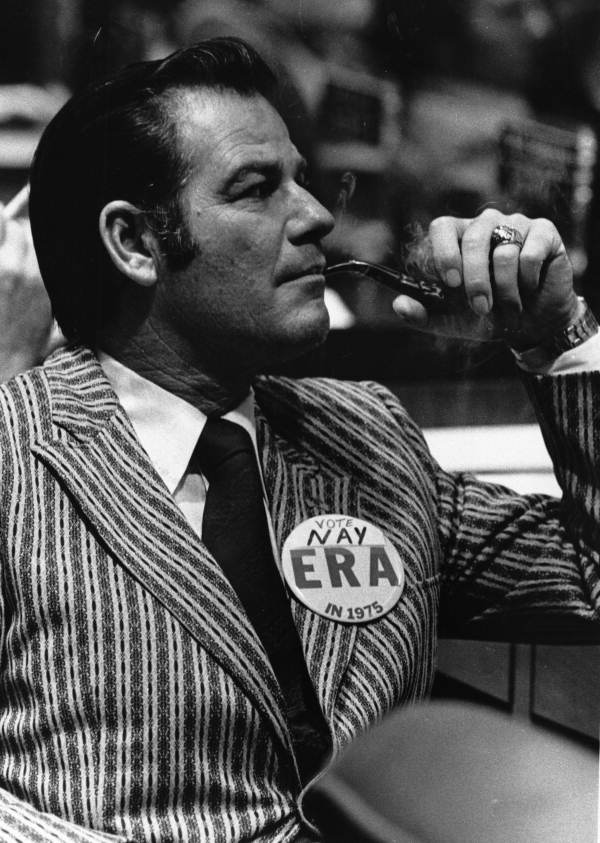

April 14, 1975

March for Equal Rights

On this day, The National Organization for Women (NOW) held a major march in the Tallahassee in support of the Equal Right Amendment (ERA). The wording of the Amendment read that “Equality of Rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex.” An estimated 3500 people joined NOW President Karen DeCrow, NOW Founder and author Betty Freidan, Representative Gwen Cherry, and actors Alan Alda and Marlo Thomas in marching from the Governor’s Mansion to the state capitol in support of the ERA. Florida Governor Rubin Askew welcomed the marchers at the capitol steps. The Florida House had already approved the amendment earlier that month and the State Senate was expected to vote on the constitutional amendment during that Legislative Session.

The ERA had been a goal of women’s rights groups after the passage of the 19th Amendment which gave women the right to vote in 1920. Suffrage leaders of the time believed adding equal rights for women to the constitution was the next step of their movement. In 1921, Suffrage leaders Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman drafted the initial version of the bill which originally read “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

It took almost 50 years before Congress passed the Amendment in 1972, opening the door for the next stage of the process. Three-fourths of the state legislatures had to approve the Amendment within 7 years in order for it to become part of the U.S. Constitution. The first 30 of the 38 needed state approvals came within the first year, and by the time of the march in Tallahassee five more state had been added.

Despite the high turnout at the parade, Florida tended to be a tough sell on the topic of women’s rights. For example, the original 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote wasn’t ratified by the state legislature until 1969, several decades after it had been added to the constitution. It was a symbolic vote by that point. As for the Equal Rights Amendment, in Florida, it didn’t even fair as well as the much-delayed approval for the 19th Amendment.

Less than a week before the 1975 parade, on April 10, 1975, the Florida House had approved the Amendment 61 to 58. But a few weeks later on April 25, the Senate voted 21 to 17 against the ERA causing the ratification effort in the state to fail. A few years later, President Jimmy Carter extended the deadline for ratification of the ERA to 1982. Florida’s legislature took up the ratification issue one final time in 1982. Once again, while the House voted in favor of it, the amendment failed in the State Senate. In the end, only 35 of the 38 states ratified the ERA before the clock ran out. Florida was never one of those states.

The State Archives of Florida says the ERA was introduced or voted upon in every Legislative Session in Florida from 1972 until the deadline ran out, but the Amendment never passed the Senate.

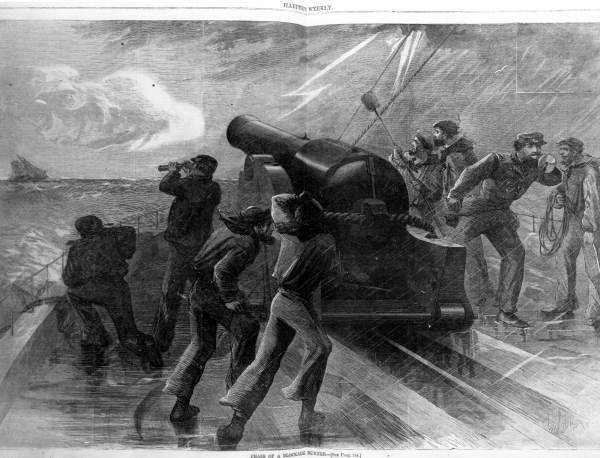

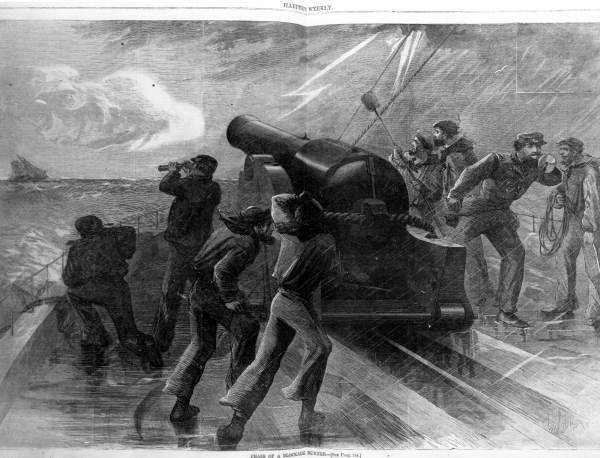

April 19, 1861

The Blockade Begins

On this day in 1861, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln started a Navy blockade of Florida and the other Confederate states. Just a week earlier, the seceded state of South Carolina fired on the Union occupied Fort Sumter starting the Civil War. Florida had been one of the earliest states to leave the Union. It also had one of the largest coastlines for the blockade to monitor. The Union Navy focused on the major ports like St. Augustine, Jacksonville, and Pensacola. Smaller ships were able to get around the blockade. More than 620-thousand Americans died in the four-year war.

Learn more about the Civil War in Florida by checking out Episode 3 of the Florida Footprints Documentary Series. That episode is called “The Confederate Road.”

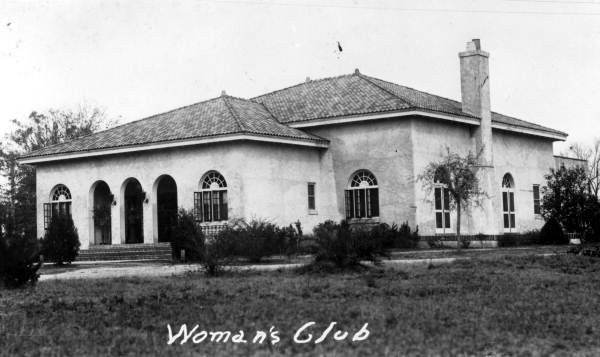

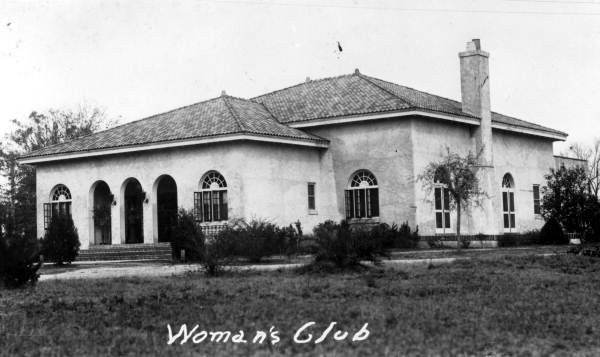

April 21, 1927

Dedication of the Woman’s Club of Tallahassee Building

On April 21, 1927, the Woman’s Club of Tallahassee held a ceremony to dedicate their building in the Los Robles subdivision. The organization had existed since 1903. The Historical Marker outside the front of the building at 1513 Cristobal Drive reads that in the early years, the group worked to raise money for the first Leon High school, supported the 19th Amendment, and helped support the Girl Scouts and 4-H Club. During World War II, the club house was used as a site by the Red Cross to roll bandages for the war effort.

According to the Tallahassee Daily Democrat, the dedication kicked off with a welcome from the President of the Club, Augusta Conradi, wife of FSCW President Edward Conradi. Other speakers at the dedication included President Conradi and Florida Governor John Martin.

The newspaper printed the planned call and response for the dedication in advance of the event.

Leader: In memory of the high hopes and the large faith of those who founded our Republic.

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

Leader: In memory of the brave pioneers of the Woman’s Club of Tallahassee and of those who gave so much of earnest effort and strong faith to the building up of our fair state of Florida.

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

Leader: In memory of those who first discovered and settled this fair region where our town now stands, who planned its early development who cared for its progress and improvement.

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

Leader: In memory of those more immediate of our own place and time who were pioneers with us in the enterprise of founding this organization of the women of Tallahassee, but who have gone on before.

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

Leader: As a meeting place for the womanhood of our town and region with all that that womanhood may accomplish in help and inspiration.

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

Leader: As a place for pleasant entertainment and friendly intercourse

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

Leader: As a home for high ideals and noble purposes.

Assembly: We dedicate this building.

April 23, 1961

New Tallahassee Airport takes flight

On April 23, 1961, The Tallahassee Municipal Airport was dedicated south of the city. Known today as the Tallahassee International Airport, the 1961 version was built to replace Dale Mabry Field which had been around since the 1920s. The Tallahassee Democrat in 1961 reported that it took six years to plan and build the new airport to the cost 3.25 million dollars. In addition to speeches for the dedication ceremony, there was reportedly quite an airshow planned for the event. While only a few thousand were expected to attend, an estimated 30,000 people jammed into the field to watch the event which included Air Force Fighter jet flyovers, stunts, military and civilian parachutists, helicopters and more.

Within two months of its opening, several Freedom Riders ending their bus trip through the south were arrested at the airport. They had tried to be served at the segregated Savarin Restaurant inside the airport.

April 24, 1834

A “Scandalous” Governor appointed

Former U.S. Secretary of War John Eaton became the Governor of the Territory of Florida on April 24, 1834. Eaton did not arrive in Florida until about 7 months after his appointment but was serving in the position when the Second Seminole War broke out in 1835.

President and Former Military Governor Andrew Jackson had appointed Eaton to the position a few years after a scandal caused Eaton to resign his Cabinet position in Jackson’s administration. It was called the “Petticoat affair” (or sometimes the “Eaton affair”) and referenced the fact that Eaton had married his second wife just a few months after her first husband committed suicide. Despite the Eatons’ protests, rumors persisted that the couple had been having an affair while her first husband was still alive. Several Washington political families refused to socialize with the Eatons because of the rumors. Eaton and Jackson both believed the rumors to be politically motivated to attack the morality of Jackson and his cabinet. President Jackson’s cabinet was fractured by the scandal. In 1831 Eaton and Martin Van Buren chose to resign while President Jackson forced several others to resign as well. Eaton served as Florida’s Territorial Governor from 1834 until March 16, 1836, when he was appointed U.S. Minister to Spain. Tallahassee’s Ricard Call replaced Eaton as Governor.

April 25, 1966

“It’s a UFO!“

April 25, 1966, will go down as the day that a sitting Florida Governor saw an Unidentified Flying Object. It was Governor Haydon Burns, and he wasn’t alone in what he saw that night out the window of his Convair plane. The Governor, his wife, three staff members, a Florida Highway Patrol captain and four reporters were traveling back to Tallahassee after a campaign stop in Orlando. They, along with the pilot and co-pilot, all confirmed seeing two red-orange lights in the sky following the plane while they were over Ocala.

Don Micklejon, a political writer for the St. Petersburg Times traveling with the Governor, told the Associated Press that the UFO was spotted at 8:52pm. “I first became aware of something when Governor Burns shouted. “It’s a UFO!” I looked out the window and saw two round lights.” Micklejon says the Governor ordered the pilots to follow the lights.

The reporter for Perry Newspapers, Jack Ledden, put a shape to the object. He said “it resembled two inverted saucers or parenthesis, connected by a long pole. The light was solid and not like that produced by a string of bulbs.”

Another reporter, Duane Bradford, who was the Capitol bureau chief for the Tampa Tribune, said at first the object, estimated to be about 15 miles away, matched the 230 mile-an-hour speed of the plane. “As the Convair’s wings dipped toward the glowing UFO, the twin pair of lights quickly diminished in size—snapping off like a light switch a few seconds after the Convair gave chase.”

The folks in the back of the plane say they could only see the lights for a total of 3 to 5 minutes, but pilots may have seen it for longer. Herb Bates, the co-pilot, told the AP that the lights followed them for about 40 miles. Bates said he contacted air traffic control in Miami. Bates was told that while air traffic controllers could see the Governor’s plane on their radar, they saw nothing else in the area.

In the days after the sighting, the Governor wouldn’t say much about the incident. He only confirmed that he saw the same thing the newspaper reporters had mentioned. However, the reporters on board said that before landing, Burns had joked with them that “I told you that my campaign would be out of this world.”

The campaign might have been out of this world for Burns, but the election was not. Burns, a Democrat Segregationist, lost in the primary to the liberal Democrat Robert King High. High, not supported by Burns in the general election, ended up losing to Republican Claude Kirk in the general election.

April 27, 1969

Westcott catches fire

On a sunny April Sunday in Tallahassee, the main administration building on Florida State University’s campus caught fire with some interesting results.

The 60-year-old Westcott building was also home to Ruby Diamond Auditorium. Cameras caught flames in the upper floors and people could see smoke billowing out of the structure for miles. Firefighters, police, administrators, and students raced to the site to see what was going on.

While firefighters rushed to put out the flames, FSU President Stanley Marshall and future Leon County Sheriff Larry Campbell rushed to Marshall’s office on the 2nd floor. Marshall wanted to get some important documents from his desk drawer. Campbell grabbed an axe from a fireman and together the duo chopped open the locked desk.

Hundreds of FSU students wouldn’t stay outside the building either. They rushed in to save paperwork, office equipment, and even a potted plant. Some they carried out, some they dropped from upper floors. The Associated Press at the time reported that a Ruben’s painting valued at $30,000 was also rescued by students.

This film was recorded by John Knight on the day of the fire and is housed by the Heritage Protocol & University Archives at FSU Libraries on Florida State University Campus.

No one was hurt in the blaze, but it took years for the damage to be repaired. The Tallahassee Democrat reported that there were not even funds available to fix the building until 1973. In 1969 the damage was initially estimated at $200,000, but by the end of repairs in the spring of 1975 the Tallahassee Democrat reported that the final cost had reached $2.1 million.

For the 6 years that it took to repair the building, employees who had worked at the administration building were spread out across campus. While initially there were concerns that the fire was caused by arson, it was ruled accidental.

In the video below that was created in 2007 for WFSU’s educational access channel, 4fsu, Reporter John Rogers talked with several people who were there that night: FSU Presidet J. Stanley Marshal, Leon County Sheriff Larry Campbell, and FSU Chief of Police Bill Tanner. All three men interviewed back then have passed away since this story was originally completed. Tanner passed away in 2012 while Marshall and Campbell both died in 2014.

April 29, 1926

A legend is born

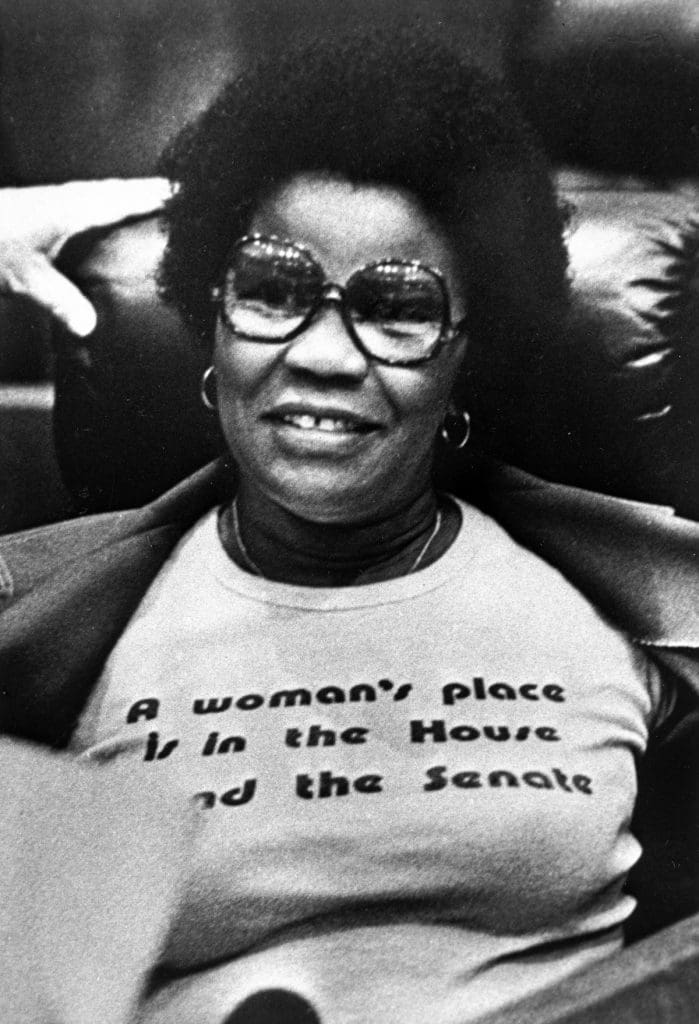

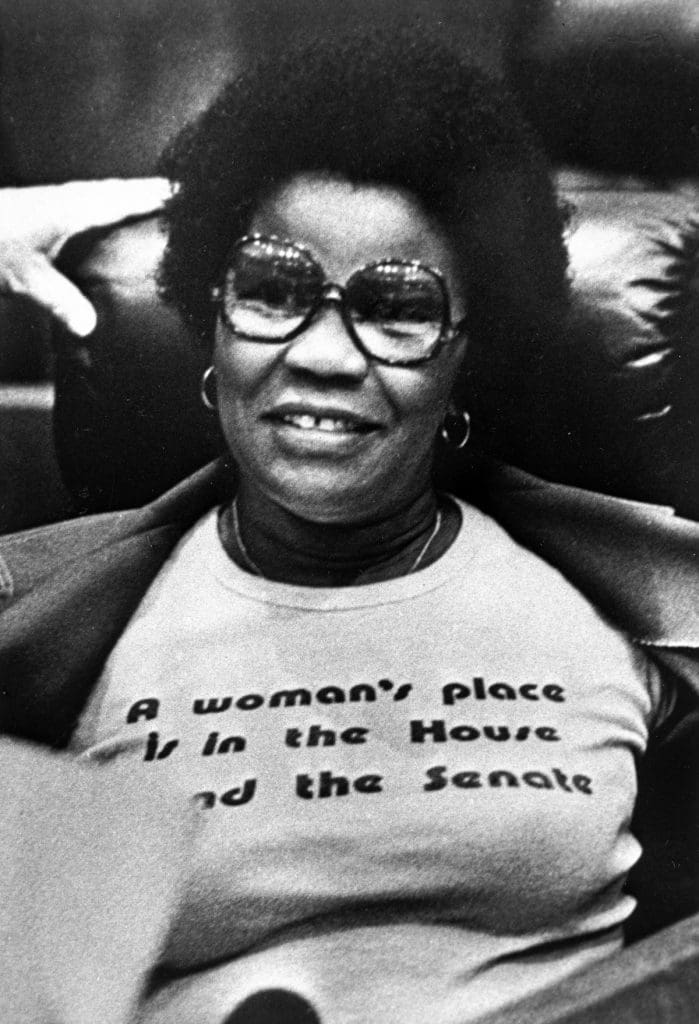

On this day, Carrie Pittman Meek was born in Tallahassee, Florida. In 1992 Meek became the first African American Woman to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Florida.

At the time of her birth, Meek’s parents were sharecroppers who already had 11 children. Meek graduated from Florida A & M in 1946 with a bachelor’s degree in biology and physical education. She received her master’s degree in those same disciplines from the University of Michigan. Meek taught at Bethune Cookman University in Daytona Beach and later Florida A & M. Eventually, she took a position at Miami-Dade Community College.

Following the death of the Gwen Cherry, the first black woman to serve in Florida’s Legislature, Meek ran for her seat. Meek served first in the Florida House in 1979 and then became the first black woman in the state Senate in 1982. In 1992, at the age of 66, Meek ran for Congress. In addition to being the first black woman elected from Florida, she was one of the first three African Americans to serve in the Congress from the state since Reconstruction.

Meek served in Congress until her retirement in 2002, winning reelection 4 times. Her son, Kendrick Meek, ran and succeeded her in the Congressional seat. In 2006, Meek’s work to help secure funds for the Southeastern Regional Black Archives Research Center and Museum on Florida A & M University’s campus prompted the state legislature to name the building partly after her along with James N. Eaton Sr.

Carrie Meek died on November 28th, 2021.

April 30, 1907

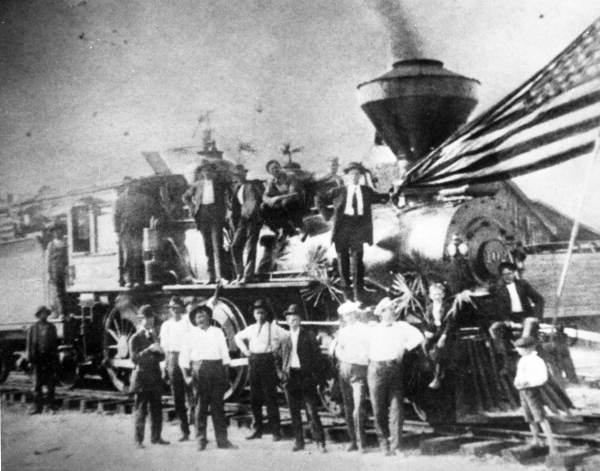

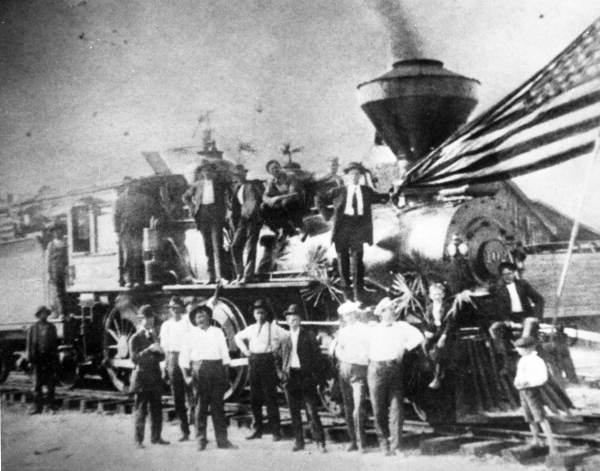

Trains arrive in Apalachicola

Transportation was always big business in the city of Apalachicola in Franklin County, but train travel didn’t arrive to the coastal city until April 30, 1907.

Boats traveling up and down the Apalachicola River would stop at the city on the Gulf on a regular basis as settlers moved into the area. Spain, England, and America all used the port city to ship goods like timber and cotton. Before the Civil War, the city was the largest port in Florida.

But while sail and steamboats were regular transportation vehicles, the city of Apalachicola had avoided a form of travel gaining popularity that first arrived in the North Florida Area in the 1830s: Railroads. The city of Apalachicola’s website says there had been an attempt to bring trains to the city in 1885. A group of Apalachicola businessmen secured a charter for the Apalachicola and Alabama Railroad company. However, they were unable to secure funding and the plan fell through.

Things changed in 1905. Charles B. Duff and his partners formed the Apalachicola Northern Railroad. It was to be a shortline railroad connecting the city to Chattahoochee which would then connect with the Atlantic Coast train line.

The ANR was completed in 1907 and on April 30th the first train arrived in town to great fanfare. People welcomed the new addition to the city. Many marked the occasion by posing with the train in photos and hanging out on the first train bridge in the area. A few years later a second line to Port St. Joe was built.

History is a work in progress, just like this page…

These are just some of the interesting facts about the history of our community. More moments, events, and people will be added to these memories as time goes on. The WFSU Local Routes team will continue to research, write, and add other historic moments to this month as time goes on. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for more new-to-you facts about the history of Tallahassee as well as our other north Florida and south Georgia communities. You can also share local historic moments you’d like to see included in our list. Email localroutes@wfsu.org.

Suzanne Smith is Executive Producer for Television at WFSU Public Media. She oversees the production of local programs at WFSU, is host of WFSU Local Routes, and a regular content contributor.

Suzanne’s love for PBS began early with programs like Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and continues to this day. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri with minors in political science and history. She also received a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of Florida.

Suzanne spent many years working in commercial news as Producer and Executive Producer in cities throughout the country before coming to WFSU in 2003. She is a past chair of the National Educational Telecommunications Association’s Content Peer Learning Community and a member of Public Media Women in Leadership organization.

In her free time, Suzanne enjoys spending time with family, reading, watching television, and exploring our community.