(Originally published June 19, 2024)

What day would you say is the “real” date to celebrate Emancipation Day? In Florida, there are two dates that are honored each year: May 20th and June 19th. Each honor different moments in the Emancipation timeline.

On May 20th, 1865, Union troops officially read and began enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation in Florida’s capital city after the war was over. Tallahassee and Leon county continue to celebrate that date today with multiple traditions, events, and days off from work. There is also the federal holiday on June 19th known and celebrated across the country as “Juneteenth.” That’s the date in 1865 when Union troops began enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in the last remaining Confederate state: Texas. Both of these dates are significant in the Emancipation Proclamation timeline, but there are also other dates out there that also are important. For example, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, marking a major change in policy that led to these other dates. So why were some dates surrounding the Emancipation chosen to be celebrated and others were not? Let’s explore the history, impact, and traditions that come with this part of our nation and state’s history.

Breaking down the initial timeline of the Emancipation Proclamation

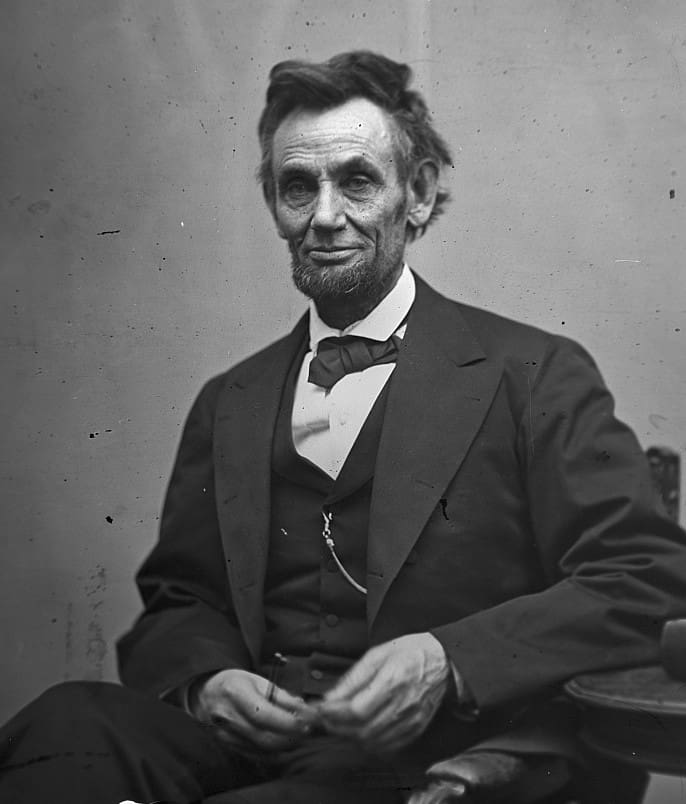

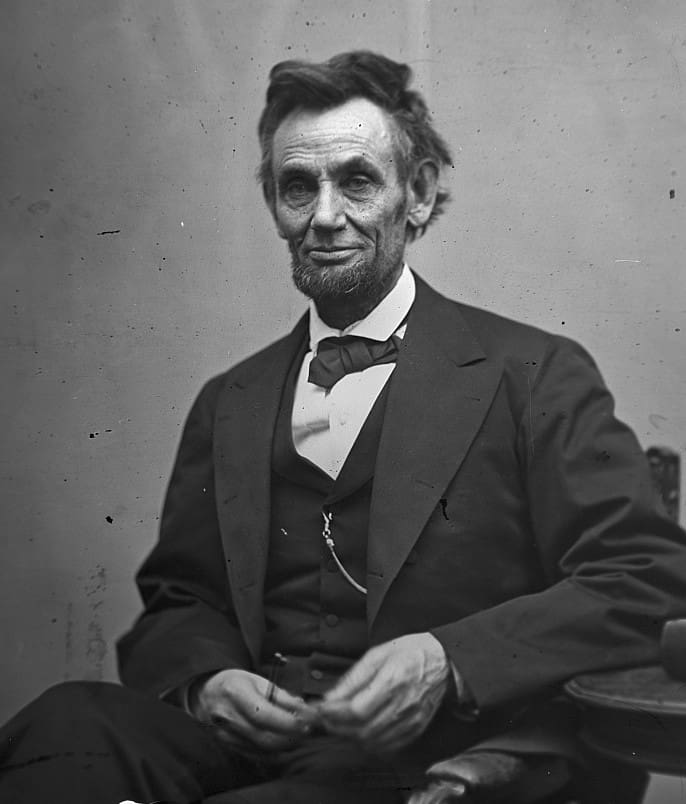

The first shots of the Civil War had been fired at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Florida had already succeeded from the Union a few months before. By 1862, the war was in full swing, and the northern states were not doing very well in the early battles. President Abraham Lincoln had managed to assemble and keep together a coalition made up of abolitionists, northerners not in favor of abolishing slavery, and the border slave states, by publicly saying his priority was to preserve the United States. Even though he hated slavery, Lincoln initially claimed he had no intention of freeing the slaves. In his first inaugural address, he said that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly to interfere with slavery in the States where it exists.”

In an editorial published in the summer of 1862, Lincoln expanded on the issue, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

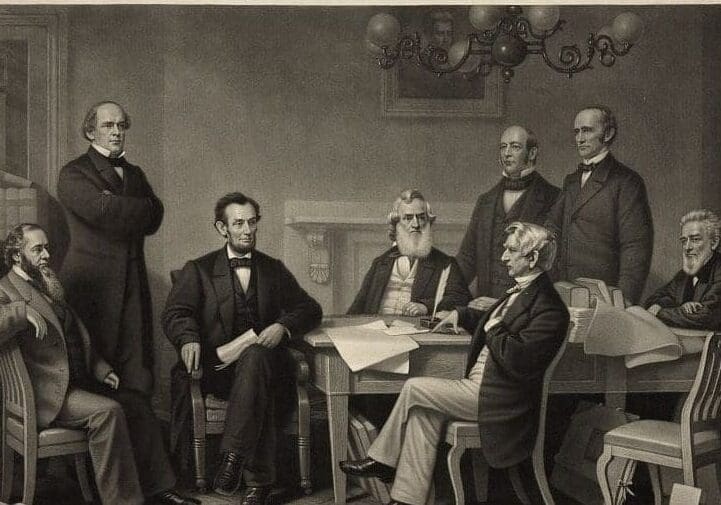

At the same time as that editorial, Lincoln had been discussing with his cabinet a way to use the issue of emancipation to force the states in rebellion to rejoin the union. Not everyone was on board with the first version of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Encouraged by his Secretary of State to wait for a major battlefield victory, Lincoln held off until Union troops stopped Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Antietam. There were more than 22,000 Americans on both sides of the war either killed, injured, missing, or captured during that battle. It became the deadliest in American military history. However, Lincoln considered it a strategic victory for the North. So on September 22, 1862, he signed the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. It said that if the rebel states did not rejoin the union by January 1, 1863, their slaves would be declared free.

The threat didn’t work.

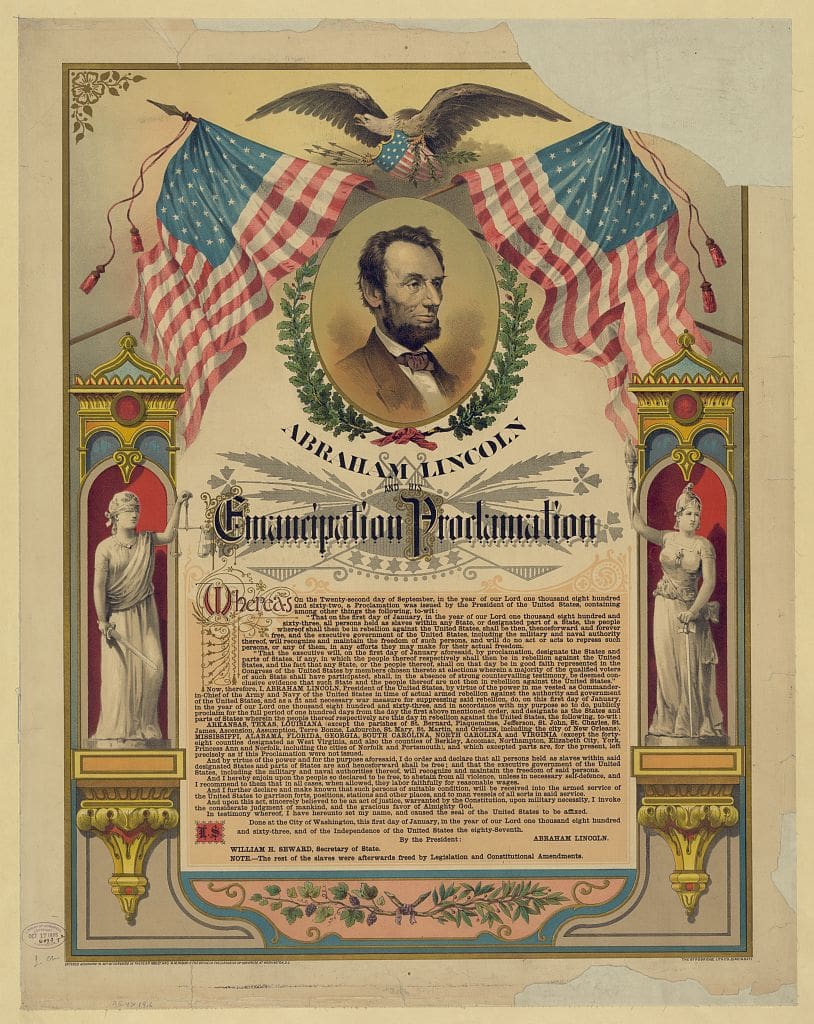

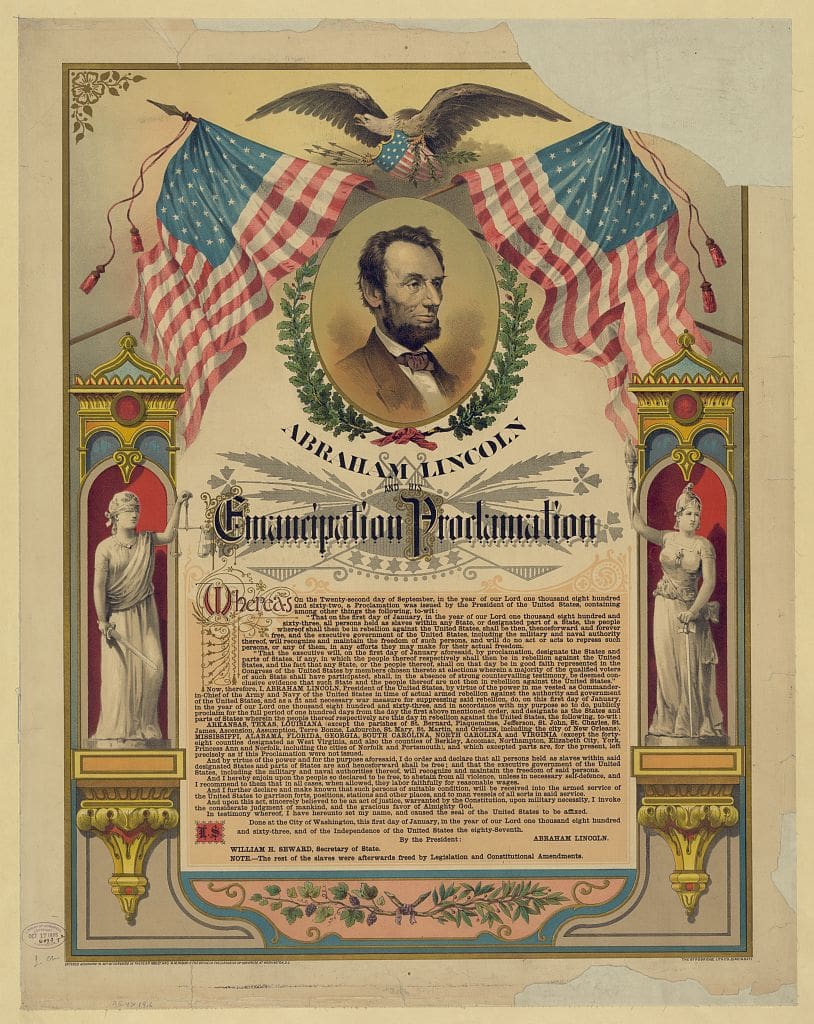

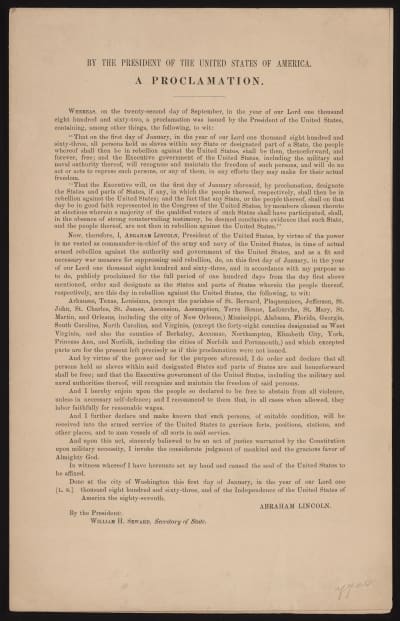

One hundred days passed without a single Confederate state returning to the Union (with the exception of Tennessee, which had been partially captured by the North). Lincoln signed the official Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. As he had promised the previous September, it stated that all people enslaved in states that were in rebellion “are, and henceforward shall be free.” But there was a catch: it did not end the institution of slavery in the rest of the United States. The Proclamation did not apply to any of the enslaved people still in the border states or any other state or territory under U.S. control (including the recaptured Tennessee). Plus, the only way the Union could even enforce the Proclamation in the Confederate states was to win the war.

The Proclamation did provide an aspect the Union could immediately enact. Black men would now be accepted “into the armed service of the United States.” By the end of the war, this policy added approximately 200,000 new soldiers and sailors to the Union’s fight.

Read the transcript of the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation is enforced in Florida

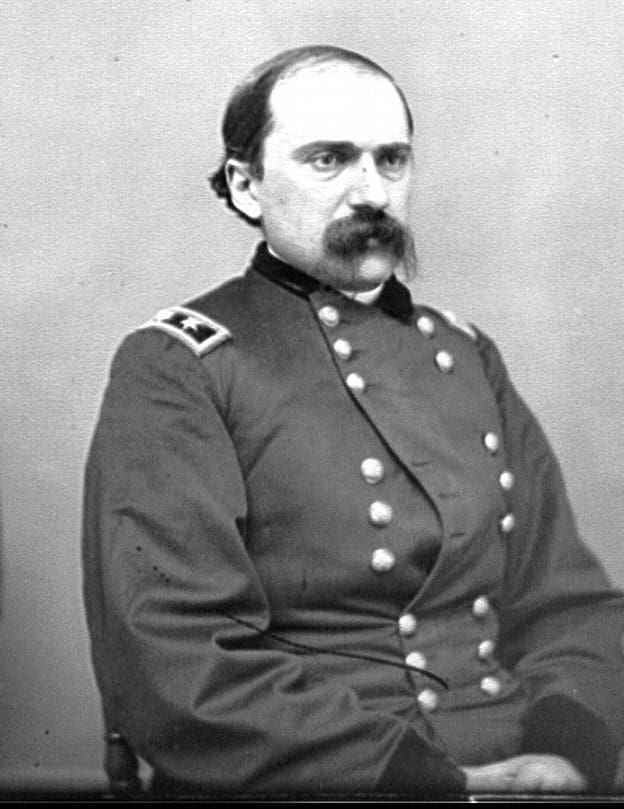

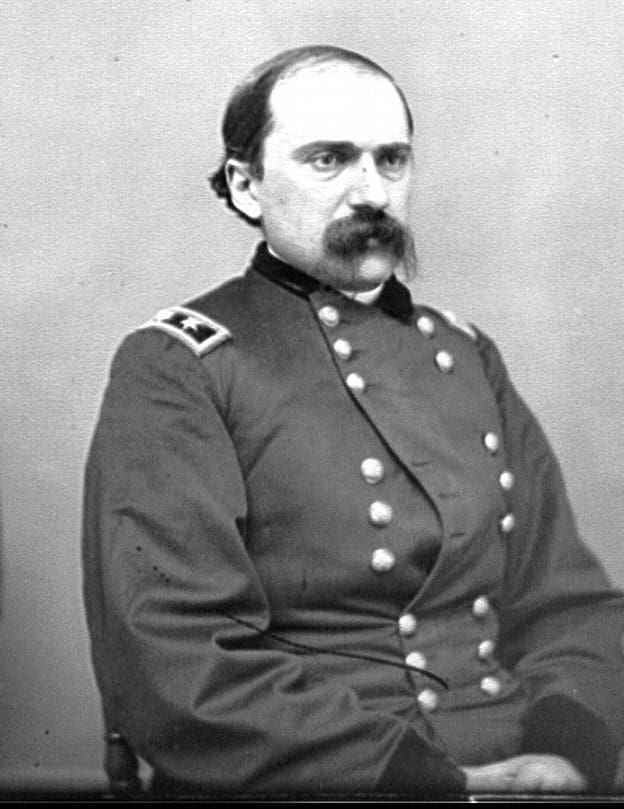

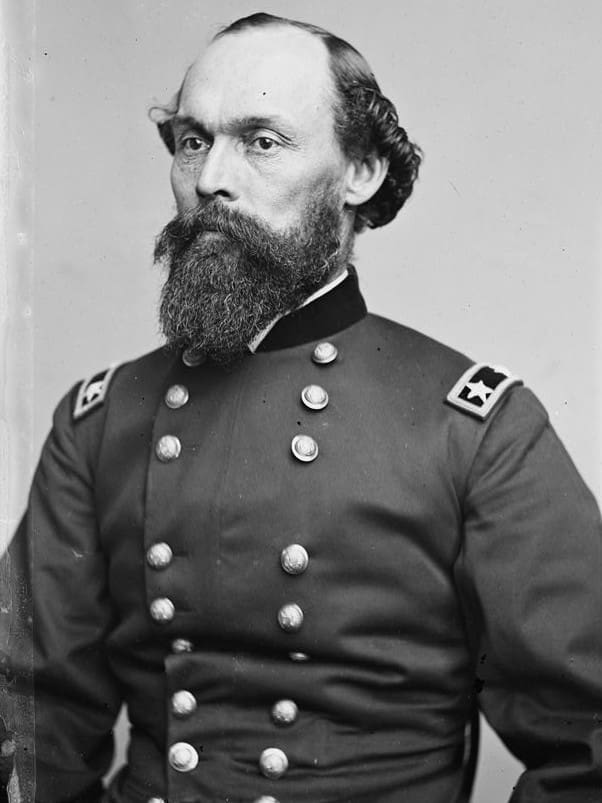

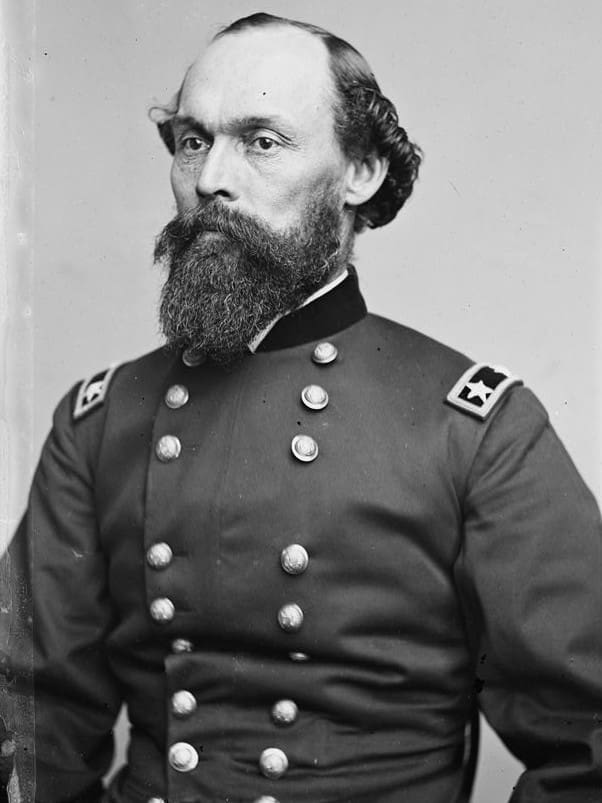

America’s Civil War essentially ended on April 9, 1865, when Confederate General Lee surrendered at the Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia. Other Confederate states began to surrender and fell under military rule at a staggered pace. On May 10th, Union troops captured Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy in southern Georgia at Irwinville (northeast of Tifton, GA). That same day, Brigadier General Edward McCook arrived in Tallahassee to accept the official surrender of the state of Florida and occupy the city. Ten days later, the details surrounding the transfer of power were complete, and an American Flag flew once again over the state’s capital building. The time had come for Florida to accept the authority of the United States Government once again. That authority included the enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation.

McCook had set up his headquarters in the home of Tallahassee’s Thomas Holmes Hagner. Built by George Proctor, one of the few free black men in the area before the war, that building is known today as the Knott House Museum. An article by the Tallahassee Historical Society says that on May 19th McCook sent officers to the homes and plantations throughout Leon County to give them a heads-up about the Proclamation and what it would mean. Before the war, enslaved people made up 74% of the population in Leon County. As the only state capital east of the Mississippi not to have been captured by Union troops during the war, Emancipation plus the beginning of military rule by the victorious North meant major changes for the southern community.

On the 20th, McCook stood in front of his headquarters and read the contents of the Emancipation Proclamation. Ellen Call Long, daughter of former Governor Richard Call, witnessed the event. She wrote in her book “Florida Breezes” that the military fired 200 guns in celebration. It was the first time the document freeing the enslaved people of Florida had been officially read in the state. More importantly, it was now recognized as something the people of Florida would be required to follow if they wanted to rejoin the Union.

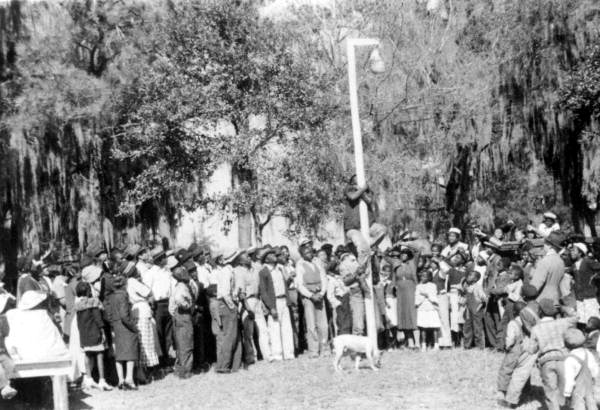

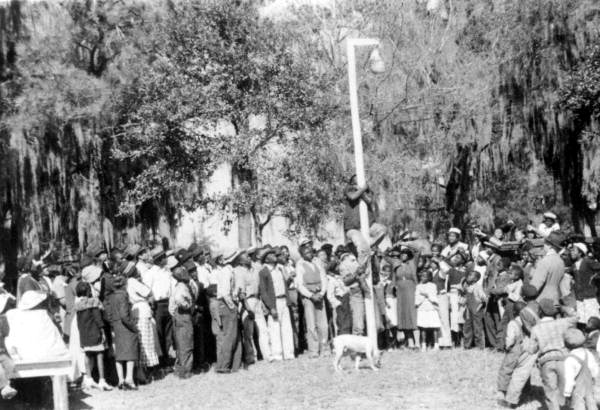

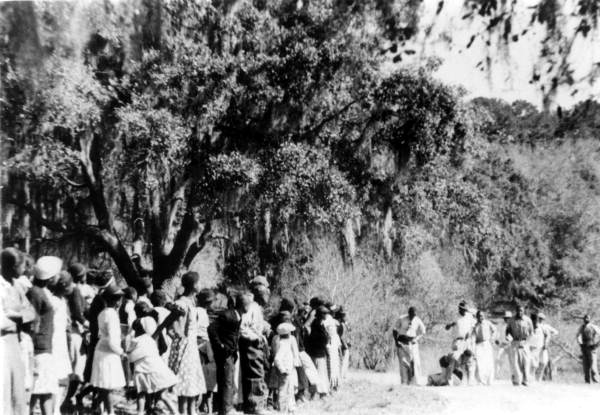

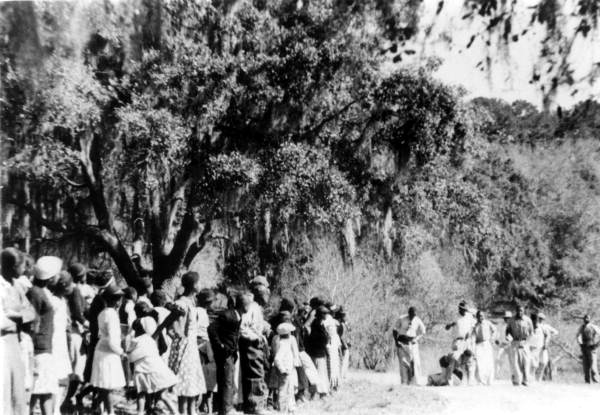

In the years that followed, May 20th was marked as the anniversary of Emancipation in Tallahassee. Local Tallahassee historian Althemese Barnes says her step-great grandmother, Debbie Edwards, along with Debbie’s friend Sarah Hill, started one of the first annual celebrations on Centerville Road that that still continues today. In 1866, the Freedmen’s Benevolent Society also held one of the first celebrations on that day. 1867, thousands of formerly enslaved people marched in a parade toward what is today’s Lake Ella and then held a huge day-long picnic there. According to the Tallahassee Historical Society, since 1871 there has also been a custom of decorating Union soldiers’ graves at the Old City Cemetery. The re-reading of the Emancipation Proclamation on the steps of the Knott House in Tallahassee also became a tradition. Reenactors from the 2nd Infantry Regiment United States Colored Troops (USCT) and the Living History Association recreate the event each year, taking place each May 20th along with other celebrations throughout the city and the county.

Florida was not the first, but Texas was the last

While May 20, 1865, is the day the enslaved people of Florida marked as their Emancipation Day, in Texas that day came on June 19, 1865. Led by Union General Gordon Granger, the troops arriving that day in Galveston made Texas the last Confederate state to have the Emancipation Proclamation read and enforced. The following year, in 1866, black men, women, and children in Texas, Florida, and other southern states began annual celebrations of their freedom. Over the years, while each state had its own day of enforcement, many of the celebrations coalesced around the Texas date that has become known as “Juneteenth.” The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture says their research of black newspapers shows that in the first half of the 20th Century, it was a strictly Texas holiday, but starting in the later half the June 19th date began to be celebrated in other cities. However, none of these celebrations were initially recognized by any state or the Federal government.

Texas changed that status in 1980 when its legislature made June 19th an official state holiday. For many years a retired Texas teacher named Opal Lee pushed for Juneteenth to become a federal holiday and more people in other states began to celebrate that date. However, no other states even recognized the day until Florida did so in 1991. Still, while the Florida Legislature declared the 19th as “Juneteenth Day,” the state has never made Juneteenth an official state holiday.

In Tallahassee, the site of the first reading of the proclamation in Florida, the Emancipation Proclamation celebration date has remained on May 20 and recognition for that date has grown in the state. In 2020, the Tallahassee City Commission and Leon County Commission made May 20th an official paid holiday for the city and county employees. In 2021, the U.S. Government made Juneteenth a federal holiday.

The date marking the end of slavery everywhere in the U.S

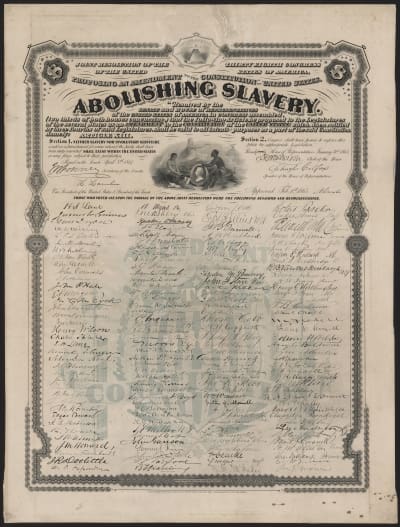

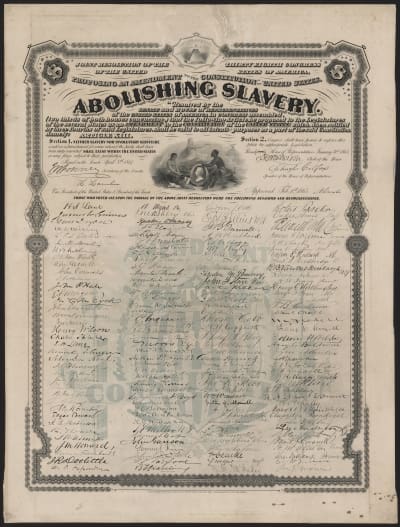

While May 20,1865, marks the end of slavery in Florida and June 19, 1865, marks the last Confederate state where the Emancipation Proclamation was enforced, slavery did not end in the entirety of the United States on either of those dates. As mentioned earlier, under the Emancipation Proclamation, people were still allowed to be enslaved in the rest of the U.S. states and territories. The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution finally put it to an official end. The one exception was the prison system.

The Amendment stated, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

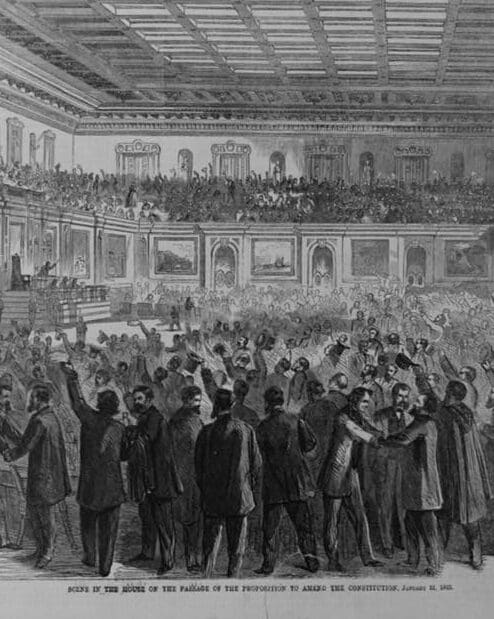

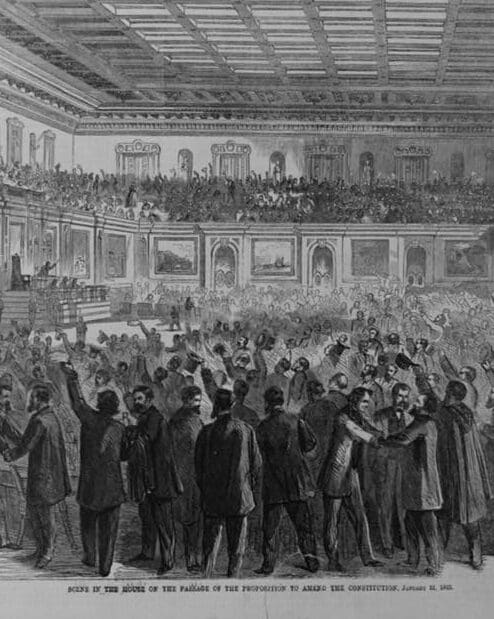

Congress passed the 13th Amendment on January 31, 1865, before the war was over. Then three-fourths of the states had to ratify, or vote, for it to become part of the U.S. Constitution. Twenty of the 36 states had already passed the amendment by the time General Lee surrendered at Appomattox. Former slave state Georgia became the 27th state to ratify the amendment on December 6, 1865, making it officially part of the U.S. Constitution. The remaining U.S. states continued to ratify the amendment after it had become part of the Constitution. Florida became number 30 on December 28, 1865. The state then ratified it a second time on June 9, 1868, when Florida adopted a new state constitution. Several states were not quite as quick to approve the amendment. New Jersey, Delaware, Kentucky, and Mississippi all rejected the amendment in their first vote. New Jersey passed it in 1866. Delaware finally ratified it in 1901. Kentucky didn’t get around to approving it until 1976 and Mississippi approved it in 1995.

Suzanne Smith is Executive Producer for Television at WFSU Public Media. She oversees the production of local programs at WFSU, is host of WFSU Local Routes, and a regular content contributor.

Suzanne’s love for PBS began early with programs like Sesame Street and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and continues to this day. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri with minors in political science and history. She also received a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of Florida.

Suzanne spent many years working in commercial news as Producer and Executive Producer in cities throughout the country before coming to WFSU in 2003. She is a past chair of the National Educational Telecommunications Association’s Content Peer Learning Community and a member of Public Media Women in Leadership organization.

In her free time, Suzanne enjoys spending time with family, reading, watching television, and exploring our community.