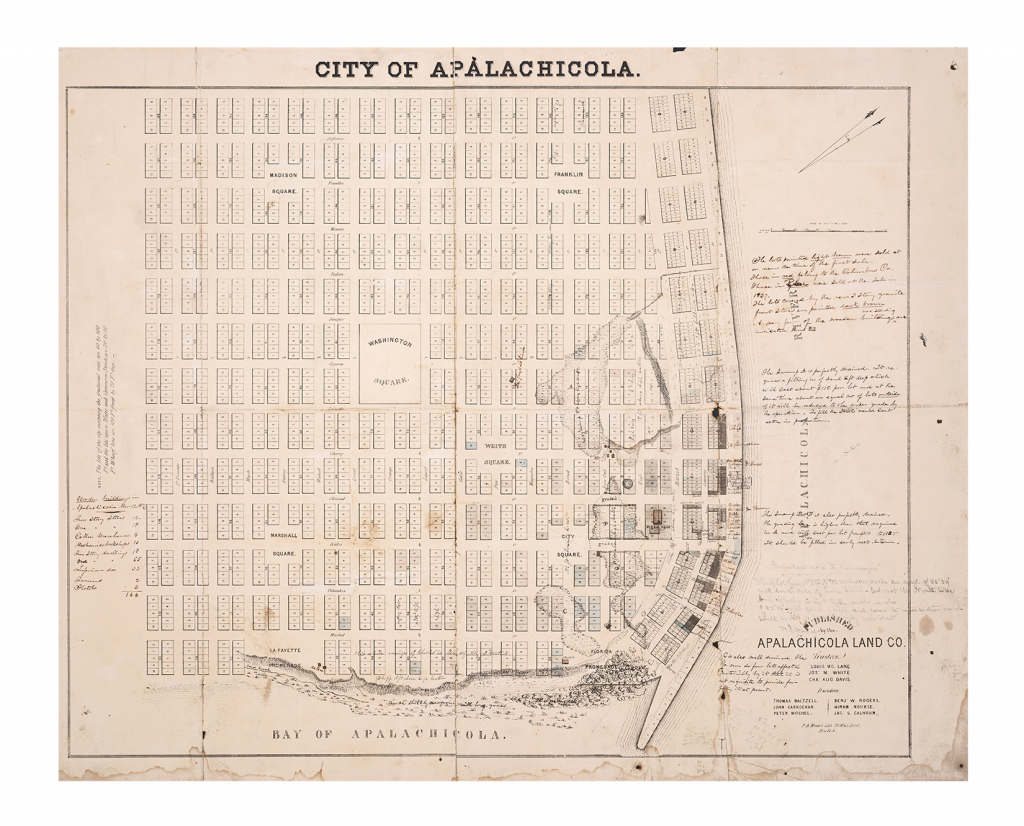

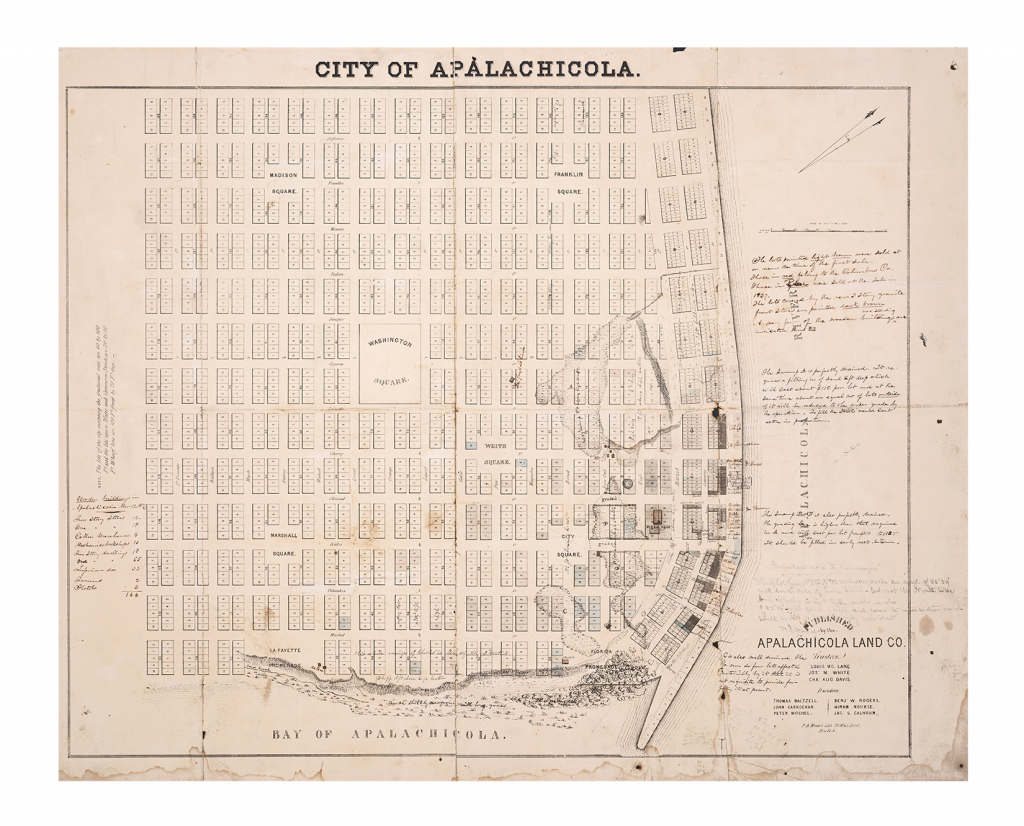

If you live in the Big Bend region of Florida, you’re probably aware of Apalachicola – the sleepy little town that gave its name to the formerly plentiful and famous Apalachicola Bay oyster. The town has been through a number of economic bases over its history. Beginning in the early 1800’s as a major seaport town, rivaling New Orleans, Mobile, and Savannah, it later sustained itself with timber, then sponges, then seafood and oysters. Today the oysters are scarce but people do arrive to visit the picturesque waterfront and explore its shops and restaurants and watering holes. The town also has more than its share of beautiful architectural examples sprinkled throughout its historic district. Originally founded in 1831 by the Apalachicola Land Company, the Supreme Court decision on the disposition of the Forbes Purchase had to be settled before the town could be formally established.

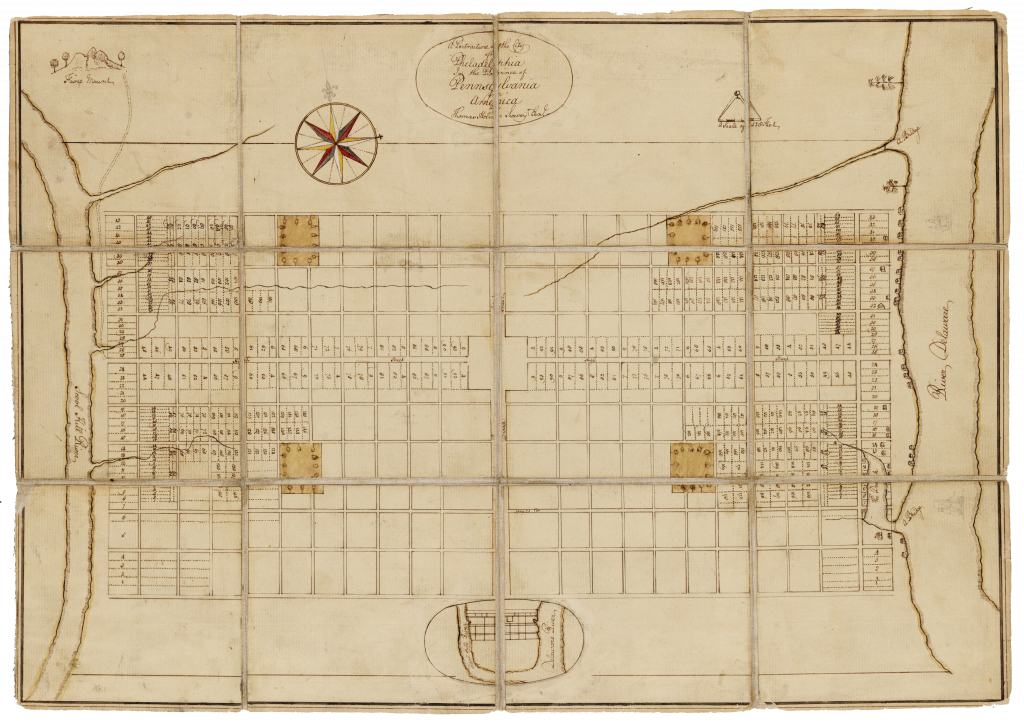

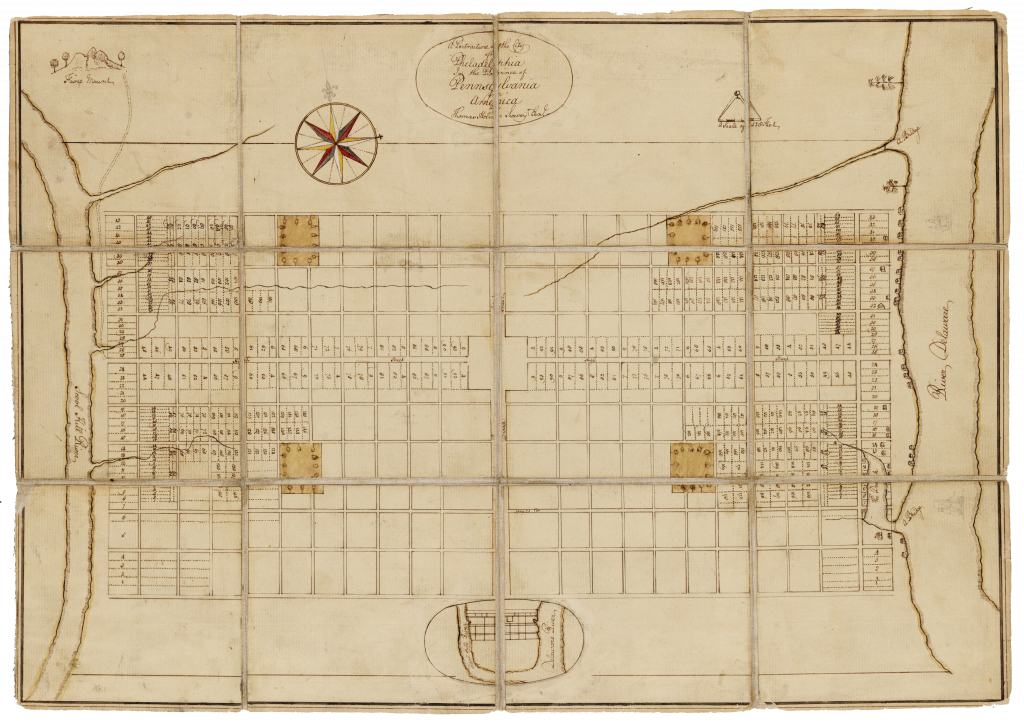

Something you might not know – the original town plat was based on the design of old Philadelphia and that Apalachicola has 6 town squares. They’re easy to miss if you don’t know what to look for, but three people there know exactly what to look for, and they’re trying to save the squares.

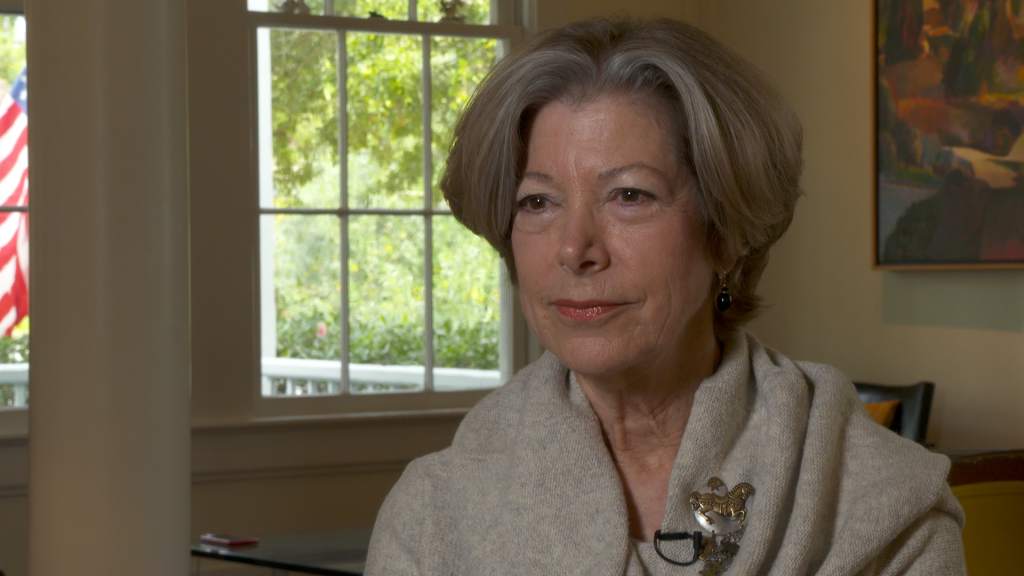

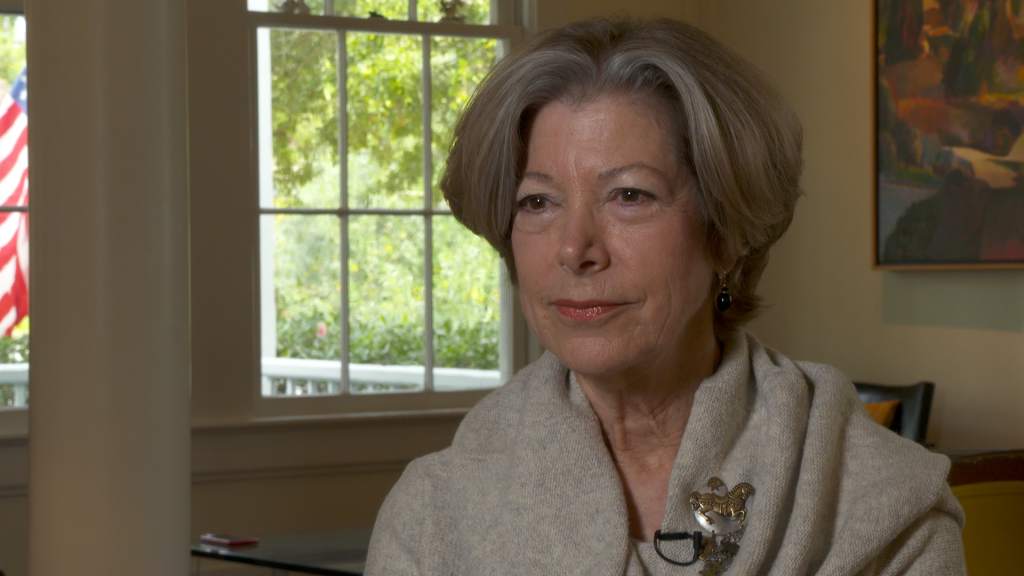

Retired attorney Bonnie Davis is the president of HAPPI, Historic Apalachicola Plat Preservation Incorporated. She has this to say about the plat, the town, and the squares, “The key to Apalachicola’s future prosperity lies in preserving its history. Because that’s what makes it unique and makes people want to come and…come to our festivals and poke around and just enjoy the ambience of it.”

“Apalachicola is a historically important …”

Diane Brewer is a transplant who watched unbridled development mangle south Florida, and says she doesn’t want to see that happen up here. “Apalachicola is a historically important, authentic town that can still be saved. And what makes Apalachicola so precious is, not just its history, but the fact that it has a…one of the, if not the only largely intact plats from that era that’s still in existence.”

“… it was too damned old.”

Willoughby Marshall grew up in Apalachicola in the 1920’s, 30’s and 40’s, and lives there today. In college, while studying architecture, he recognized the resemblance of the town’s layout to the 17th century William Penn-Thomas Holme design for Philadelphia. “I was aware there were four squares in the town and a central square. And it didn’t really sink in until I was in college and learned that Philadelphia had, as I said, the same plan and many of the same street names and squares. There’s four squares and a diagonal square, just like this. And I knew that Philadelphia didn’t copy Apalachicola, because it was too damned old.”

Over time, the city allowed roads to run through all but one of the squares, effectively turning the squares into intersections. The effort to save the squares is based on the idea that preserving Apalachicola’s history will be the driver of the town’s economic future. In 1974, Marshall was awarded a grant from HUD to study Apalachicola’s economic viability through historic preservation. That was the genesis of the effort to save the squares. He says, “People are very much interested in preservation and in old architecture and city plans, especially old city plans. And I saw how this could very much be an attraction around the country and could bring life…help bring life back into the town.”

And all these years later, Brewer adds, “Heritage tourists stay longer and spend more money, according to this study, than tourists who are going to come and go to the beach for the weekend. And they come because Apalachicola…is authentic. So the next phase of Apalachicola’s prosperity is from heritage tourism.” The study Brewer is referring to is the 2010 Executive Summary Economic Impacts of Historic Preservation in Florida by the University of Florida.

Davis adds this nugget of practical wisdom, “I’m a historical preservation nut, but there’s such a clear tie, in this instance, between historical preservation and economic prosperity that, uh, even if you’re not interested in it, there’s good reason to pursue it.” Finally she adds, “I just don’t think there are many places in Florida left like that and this one is really worth preserving.”