FAMU rides a wave of HBCU revivals

At Florida A&M University, the country's top-rated public historically Black university, the moment is a double-edged sword.

Subscribe now

Episode 7 by Margie Menzel, WFSU Local Government Reporter

Edited by Lynn Hatter & Patricia Moynihan

Listen to the complete episode below. Subscribe now (by choosing your preferred platform) to be notified of upcoming episodes in this series. The text article below is abbreviated and may not include everything in the audio portion.

“Is this a moment or a movement? It’s going to be a movement for the universities that are prepared for it, it’s going to be a moment for those who are not.” — Dr. Reginald Ellis

Historically Black Colleges and Universities, known as HBCUs, are in a period of resurgence. They have more status, thanks to high-profile business partnerships and celebrity endorsements. They have more money, due to recent increases in federal support and philanthropic giving. And for many Black students who could have gone to prominent, mostly white schools, HBCUs have become the first choice.

Since 2010, overall college enrollment has been on a steady decline. And during the pandemic, it plummeted 9.6% according to the Education Data Initiative which uses federal figures to track the numbers.

But since the pandemic, HBCUs are seeing a surge that predominantly white institutions are not. FAMU President Larry Robinson called it “remarkable” in his February 2023 state-of-the-university speech. “Eighteen-thousand-plus first-time-in-college students have applied to Florida A&M University,” he said. “To put that in perspective, that is 10,000 more than had applied just a year ago at this same time.”

At FAMU, the country’s top-rated public HBCU, the moment is a double-edged sword as the school initially struggled to adapt to the heightened attention and interest it started receiving in 2022.

That year, the massive influx of students expecting housing on campus left the school flat-footed and on the receiving end of negative headlines. And also in 2022, just before making a trip to the University of North Carolina for what was billed as an HBCU Celebration Game, at least 20 football players were deemed ineligible to play, leading to scrutiny of the program. For many FAMU observers, it felt like the same old story of HBCU incompetence, a stigma that many say is unfair and unearned.

Now is a time of renewed interest in HBCUs. But given that they’ve had bursts of growth in the past, some question whether this is just a trend, doomed to be short-lived.

Reginald Ellis, FAMU’s Assistant Dean of the School of Graduate Studies and Research and a professor of history, weighs in on the apparent resurgence. “That’s up to the HBCUs themselves, and that’s where the leadership comes into play,” said Ellis. “And so, one of the things I have asked myself: ‘Is this a moment, or a movement?’”

This is a story about the challenges faced by Florida A&M University as it struggles to accommodate growth, challenge racism, and make way for a new group of students who chose FAMU over elite, predominantly white institutions.

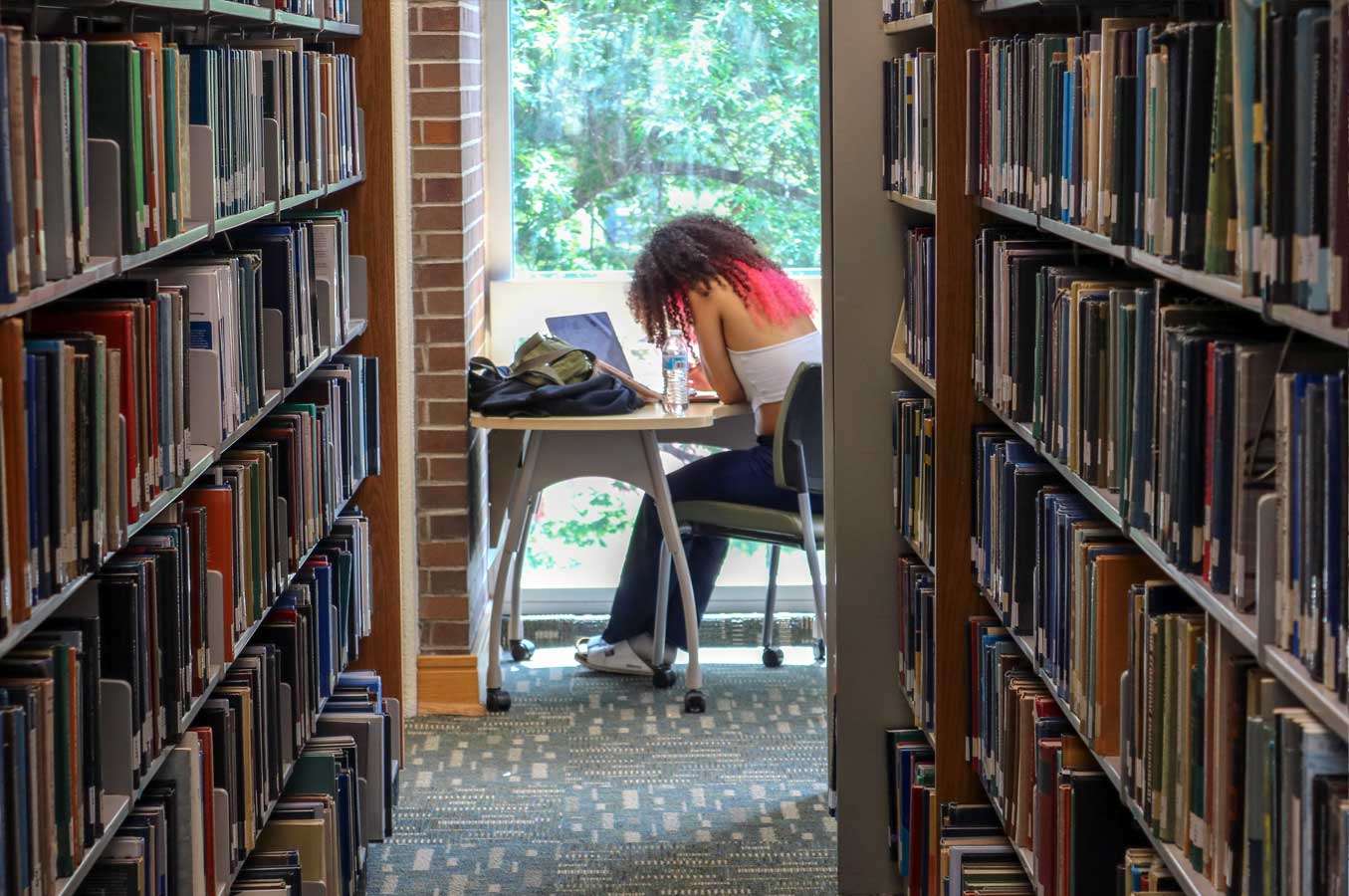

Finding a Safe Place

In 2021, then-16-year-old Curtis Lawrence III announced he would bypass schools like Yale and Harvard to attend FAMU. That same year, top football recruit Travis Hunter reneged on his plan to play at Florida State University and announced he’d be heading to Jackson State. Both developments went viral. And people wondered why two such talented Black students would forgo opportunities to attend elite, predominately white programs.

“People like to call it a FAMU-ly,” Lawrence said. “Everyone knows everybody on campus, we’re all taking care of each other. It’s definitely a home.”

Lawrence, now 19, said FAMU reached out to him in a way no other school did: he met the president, the professors, and he said, “people in different offices, they made sure to let me know that when I was here, they’d take care of me...and I wouldn’t have to have any worries about living on my own.”

And does he feel at home?

“Yeah,” he said, “Yeah, I do.”

Increasingly, Black students who could go to an Ivy League school are choosing HBCUs. But this isn’t the first time it’s happened—at least, not at Florida A&M. The university was named Princeton Review’s College of the Year in 1997—an honor that came, in part, by besting Harvard in recruiting National Achievement Scholars…the top Black students in the country based on their SAT scores and high school grades.

And yet, since the enrollment highs of the 2010s, overall enrollment at institutions of higher learning has declined. Florida A&M, like its predominantly white and HBCU counterparts, experienced a slump.

Then came a series of racially charged incidents at other schools, such as a 2015 scandal involving the University of Oklahoma chapter of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity. Its members were videotaped singing a song with racist slurs like the "N word," and references to lynching.

When the video surfaced online, SAE’s national headquarters shut the chapter down.

in this episode: featured song

- TaReef KnockOut, "Small Town"

- Watch the Official Video

FAMU’s Ellis said the scandal caused a lot of soul-searching for Black students. “Black students, quite frankly, said, ‘Why would I continue to invest in universities – because colleges and universities are a major investment for a family now,” He continues, “And so, they’re saying, these students of color are saying, ‘Why would I continue to invest in a university that really, holistically, is not embracing my presence on this campus?’ And what they started to see or re-imagine, or reconsider is HBCUs.”

The SAE racial scandal was far from the last. The 2016 racially-charged election cycle brought further enrollment growth.

Then came 2020.

“You can directly point to the death of George Floyd and the protests and the situations that happened on campuses that were not HBCUs, and students did not feel safe on those campuses,” said HBCU Gameday's Vaughn Wilson, a former FAMU administrator. “It is why the surge in — while college admissions were going down across the country, HBCUs were surging.”

2020 was also the year Breonna Taylor was shot to death in her home during a botched police raid, and Ahmaud Aubery was murdered in what was held to be a hate crime while he was out for a jog. All three victims were Black.

Curtis Lawrence, the young FAMU scholarship student, had been dual enrolled at George Washington University while in high school, but not involved socially on that predominantly white campus.

“Here at an HBCU it’s a very different environment,” he said. “You’re not going to experience the same kind of racial events that you would experience outside of an HBCU, at a PWI or just generally in the world. And so, as a Black man in a society that…isn’t a lot of Black people, an HBCU offers that kind of safety of being away from that, at least for four years. And then preparing you to go into that to be ready for, you know, going into the rest of the world.”

At HBCUs, the enrollment slump was short-lived.

FAMU Is Caught Off-guard

The Fall 2022 semester brought a huge demand for on-campus housing and a huge shortage of it. FAMU had been planning for growth, tearing down older dorms to make room for new ones. But what administrators didn’t plan for was that all the students the school accepted would enroll. And that due to rising rental costs, they would all want to live on campus.

“Now, normally when you have that situation, there’s a formula of a percentage of people who will actually come,” said HBCU Gameday’s Wilson. “This year, that number far exceeded the formula that every college in the United States of America uses. Those numbers of people who applied and got accepted who actually came far exceeded the formula. So FAMU got caught off-guard with the housing.”

Other HBCUs had similar problems at roughly the same time. But before FAMU’s housing uproar died down, some 20 members of the Rattlers’ lauded football team missed a major season opener due to eligibility problems. It turned out the university’s 300 student-athletes had just one compliance officer—prompting the team to write President Larry Robinson a lengthy letter that he later praised. The school quickly fixed the compliance issues, but not before being heavily criticized in the media.

Robinson took questions from reporters after meeting with the football team.

“We’re continuing to work with our compliance team, medi-coach, and others who submit just the names to the NCAA for clearance,” he said. “And we have another four or five that we’ll be submitting as early as tomorrow to hope to get them cleared — perhaps in time for this game — but we don’t know for sure because that’s in the hands of the NCAA.”

During the past two decades, FAMU has experienced major ups and downs. It’s cycled through presidents and bad financial audits, landed on accreditation probation due to a hazing scandal, and faced perennial problems in disbursing financial aid.

FAMU’s Ellis said some, but certainly not all, of the disorder owes to historical funding disparities that go back decades, and the widespread ramifications of those decisions.

“So, we know the back end, right?” he said. “We don’t have, perhaps, enough financial aid representatives, we don’t have enough academic coordinators, we don’t have enough administrative staff in each office, perhaps our faculty is overburdened teaching four or five classes a semester and still having expectations to do the research but also do the community service aspect because we are a public land grant university. When you start to look at that, how are the resources that are being allocated and the lack of that resource — how is that impacting the university?”

FAMU Students Bring a Potential Class-action Lawsuit

Last fall, six Black FAMU students sued the Florida Department of Education for years of school underfunding, amounting to a shortfall of roughly $1.3 billion. More recently, in a letter to the state, the U.S. Department of Education placed that figure at closer to $2 billion.

The students’ attorneys compared Florida A&M to the University of Florida since they’re the state’s two public land-grant universities.

...as the number-one public HBCU in the nation, we definitely deserve more credit than we get...

“There’s no way to move forward unless we right the wrong of institutional racism in this country,” said Josh Dubin, the Miami-based civil rights attorney who represents the students.

“And you can’t run from it. You can’t hope that it’ll cure itself. You have to either be willing to enter the arena and join the fight or not.”

The plaintiffs say the state has failed to meet all its funding obligations to FAMU. In Tallahassee, home to FAMU and nearby predominantly white Florida State University, the differences are stark.

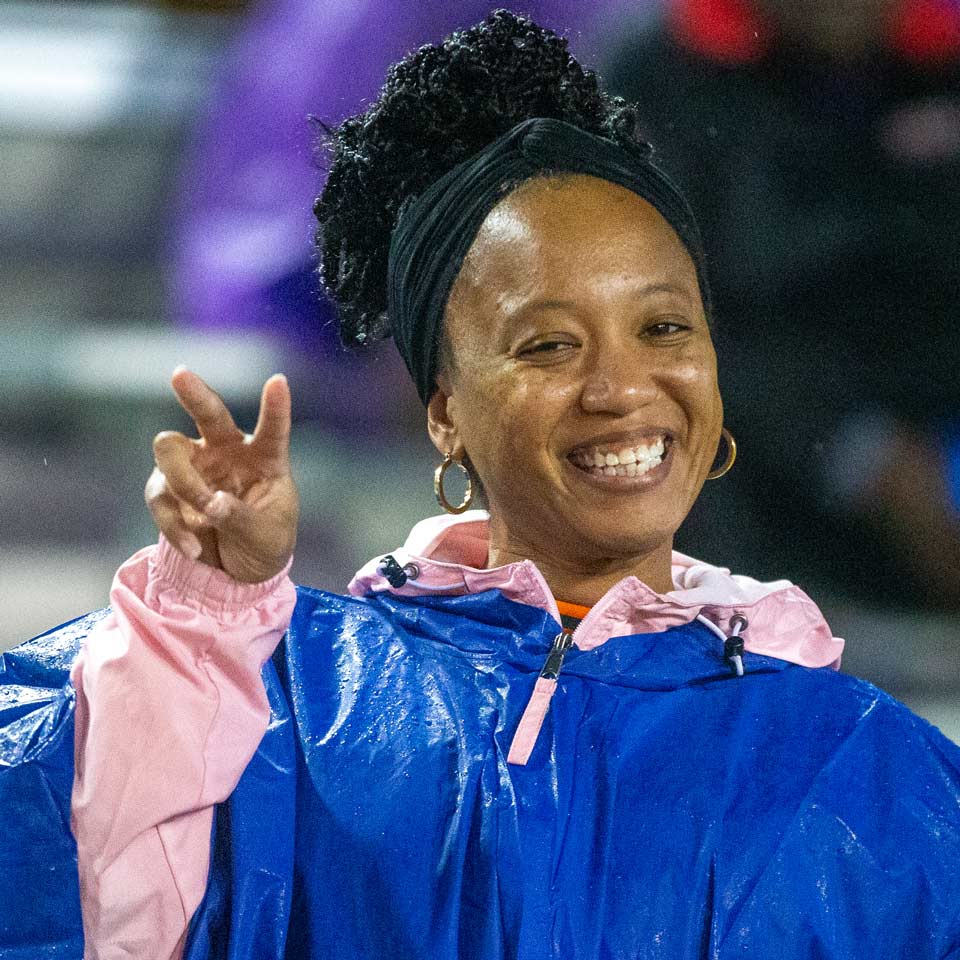

Britney Denton a doctoral student at FAMU’s College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and one of the six student plaintiffs comments on the disparities, “The buildings have been more updated at Florida State. They have more recently built facilities, much better resources that have been allowed to them throughout time.”

“Florida A&M University has not always been privy to those same privileges, and we just want to fight to say we deserve those, too.” Denton continues, “And especially as the number-one public HBCU in the nation, we definitely deserve more credit than we get.”

Former state Sen. Arthenia Joyner was a FAMU student in the 1960s. Back then, she was one in a group of student activists demonstrating in downtown Tallahassee to integrate stores, buses, theaters, and restaurants.

"The alumni of FAMU who were in the Legislature when I was there, we came together,” she said. “And every year we had to fight for whatever funding that we got.”

Joyner was among the last graduates of the original FAMU College of Law, which was shuttered by the Florida Legislature in 1968. She took her final exams as the shelves were being stripped of law books, later given to FSU. The Legislature re-established FAMU’s law school in 2000, but Joyner continued to fight for funding for the university throughout her 12 years as a legislator.

“And it was always a battle,” she said. “Never once could you just assume that you would get top dollar or come anywhere near what was adequate in order for the institution to function at the level that it should.”

Arguments in the potential class-action case mention both the engineering program (shared with Florida State) and the FAMU law school (now located in Orlando) that originally closed as Florida State's opened. In comparison, Maryland and Alabama have settled lawsuits over historic underfunding by their state governments. In 2021, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan signed a bill that will provide $577 million to the state’s four HBCUs. In Alabama, in fiscal year 2005, more than $200 million went to HBCUs Alabama State University and Alabama A&M University when the federal lawsuit Knight v. James was settled. And the state of Tennessee recently concluded it may owe its public HBCU up to $544 million.

A federal judge has refused to dismiss the lawsuit over FAMU’s funding.

“We do deserve to be treated equally, as those students that are literally across the tracks from us,” said Britney Denton, standing on the courthouse steps afterward. “It’s not fair that we aren’t able to get the same opportunities, we aren’t allowed to get the same amount of money, we aren’t allowed the same education in the same city as another school that has every opportunity in the world.”

With Florida’s Republican leaders dismissing concepts like 'diversity, equity, and inclusion' and a so-called WOKE agendas, higher education in Florida is growing ever more political and contentious.

FAMU President Larry Robinson knows FAMU students have always been ready to put their institution at odds with state leaders. WFSU asked what he thinks of the potential class-action lawsuit.

“Do you think it's fair?” we asked. “Are you going to do anything about it?”

“Well, the good thing is, I won't have to,” he said, laughing. “I will say this about our students: Whether you're talking about the football players who wrote me a letter, or the people who marched in support of desegregation back in the fifties and the sixties, we have at FAMU some of the nation's most socially-conscious and aware students on the planet...I am not a party to the lawsuit, but at the same time, it's the vision and perspective of our students and those involved in the lawsuit that think there's some merit to it.”

“Aren't you walking kind of a fine line, since they're suing people that have some control over your institution?”

Well, it's always a fine line,” he said. “I have to represent Florida A&M University. That's what the Board of Trustees hired me to do, and I am going to do that to the best of my ability”

As to the university’s own issues, Robinson knows there are unresolved problems. He’s already had to answer to his trustees for the housing and athletic program. And he knows that the perception of HBCUs isn’t universally positive — perceptions, he notes, rooted in stereotypes. But that, he believes, is changing.

“This notion that HBCUs were created to deal with students who otherwise couldn’t be successful anyplace else is one of the biggest fallacies in higher education,” Robinson said. “And so, what I think is the social justice movement helped to pull the curtain back on and it gave us a voice to tell the real story to those out there who would be willing to listen.”

Robinson came to FAMU in 1995 as a visiting professor. In 2010, he took a leave of absence to serve in the Obama Administration. In 2012, he was tapped as provost, followed by several stints as interim president. He was named president in 2017 after the previous one was fired, overseeing a period of relative stability at FAMU.

Educated at an HBCU

Robinson’s higher education began at an HBCU. Since these institutions were created in the wake of the Civil War, they have been widely credited with creating and expanding Black professionalism and generating Black wealth.

Robinson earned his bachelor's degree in chemistry summa cum laude from Memphis State University and his doctorate in nuclear chemistry from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

in this episode: featured songs

- Repertoire of the FAMU Marching 100

- Vist FAMU Marching 100's website

“Those of us who have been in the HBCU community — this has been our secret, right? Not that we try to keep it from people, but we have known this,” he said. “And I personally have known it because I had the privilege of attending an HBCU my freshman year at Memphis Lemoyne-Owen College, and transferring to the PWI across town and seeing the drastic difference in how I was accepted as an African American male trying to major in chemistry.”

Now FAMU’s applications have soared. The school has received more than 20,000 requests for admittance in the fall. Robinson points proudly to the 3.98 GPA of the newly admitted class. But he acknowledges feeling a bit conflicted about that.

“So, Larry Robinson, back in the day, wouldn’t be coming to FAMU,” he said. “And I’m really worried about what that means, because I’m worried about every student who comes and every student who doesn’t get in because that could be another person to help us as a nation and a society get to where we need to go. And of course, that student’s family and their community as well.”

FAMU has become much more exclusive than ever before. So, what happens when an institution built to expand opportunity, equity, and inclusion for people of color climbs beyond the reach of those for whom it was built?

Reginald Ellis has spent his life on the campus of Florida A&M University since he was a small child.

“The question I raise, ‘Is this a moment or a movement?’ – It’s going to be a movement for the universities that are prepared for it, it’s going to be a moment for those who are not, because those students, after a while, are going to say, ‘I tried it, and it didn’t work out for me.’”

The acceptance rate at FAMU is roughly 35%, compared to the University of Florida’s 30% and Florida State University’s 37%.

Last year the New York Times reported, “There is also a growing recognition among policymakers and predominantly white schools of the value of HBCUs, and the fact that they have long operated at a disadvantage.”

In June, after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down affirmative action, the Brookings Institute wrote that the decision means that “HBCU investment is more important than ever before.”

Britney Denton sees the disadvantage clearly. She and her fellow plaintiffs are fighting to end it. But FAMU – where student activism is an honored tradition – will always be her first choice.

“I really do hope and pray that I will be able to live up to that type of standard, because there are many people who have come from FAMU that they’ve made dramatic changes in the world, in the state, in the United States,” she said.

“They’ve been able to make a change simply by having something to say. I hope to follow in their footsteps and to lead my classmates and my peers and my colleagues in a very similar march that they did.”

Brought To You By

the dedicated storytellers at WFSU Public Media

- Lynn Hatter - Lead

- Gina Jordan

- Regan McCarthy

- Valerie Crowder

- Rob Diaz de Villegas

- Tom Flanigan

- Margie Menzel

- Patricia Moynihan - Lead/Website

- Rheannah Wynter - Promo/Graphic Producer

- Lydell Rawls - Social Media

- Daniel Williams - Web Assistant

- Chris Womack - Logo Design

- Erich Martin - Photography

- Suzanne Smith - Lead

- Kim Kelling

Director of Content & Community Partnerships

-

Advisors

- Dr. Reginald Ellis - Florida A&M University

- Dr. Andrea Oliver - Tallahassee Community College

- Dr. Kwasi Densu - Florida A&M University/Florida State University

- Dr. Jamil Drake - Divinity School at Yale University

This project has been funded by a grant from

Funding for this program was provided through a grant from Florida Humanities with funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this podcast do not necessarily represent those of Florida Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

© 2026 WFSU Public Media. All rights reserved.