For some Black people in the South, land is more than wealth. It's community and culture

The positive role gardens play in Black communities, then and now.

Subscribe now

Episode 3 by Rob Diaz de Villegas, WFSU-TV

Edited by Lynn Hatter and Patricia Moynihan

Listen to the complete episode below. Subscribe now (by choosing your preferred platform) to be notified of upcoming episodes in this series. The text article below is abbreviated and may not include everything in the audio portion.

Miaisha Mitchell is giving a tour of the raised beds of wood and cinder block crowded with basil and rosemary that dot the iGrow Community Garden in Frenchtown, on Dent Street. Long, red hot-peppers are ready to be picked. Mitchell is the Executive Director of the Greater Frenchtown Revitalization Council which coordinates programs related to health and young people.

All around the garden are people at work weeding or harvesting fruit from trees. “What you see here is a whole community of folk who volunteer, you know, to come out and share,” she said.

Mitchell grew up in one of Tallahassee’s historic, Black enclaves—Smokey Hollow. As she wanders the garden she stops near a persimmon tree. She said it reminds her of her youth.

“Oh, they're beautiful,” Mitchell said of the fruit—a round, yellow-orange variety. “But right now, they're not quite ripe. This tree is indigenous to Tallahassee. When we lived in Smokey Hollow, this was one of the favorite foods that I used to eat all the time.”

The Smokey Hollow that raised Mitchell is long gone, its homes destroyed decades ago to make way for government buildings, and Apalachee Parkway—which stretches to the front steps of the historic capitol building. Today, the neighborhood exists only in replica structures commemorating what has long been lost.

Until the 1960s, Tallahassee’s majority Black Frenchtown and Smokey Hollow neighborhoods were places where people grew and shared food. Whatever couldn’t be grown could be bought at nearby grocery stores. That was by necessity, given the racial and legally enforced segregation of the time. Today, Frenchtown, which is where iGrow is located, is a food desert.

“This is how we feed our family,” said Rose Garrison, a garden volunteer. “This is when we canned, we canned everything. Somehow, we have gotten away from it, either through generations of not doing it or thinking it tedious to do. And we have gotten away from it. But we've got to get back to our roots. This is our roots,” she said while pulling weeds and watering the plants. The “this” being the work of garden-tending. Minding the garden reminds Garrison of her childhood in Alabama, when gardening wasn’t a hobby: it was a necessity.

“ We put things in jars. We shared. You know, we got together and, ‘Okay. It's time now to go get to pick the corn. Go get the corn.’ Everybody in the neighborhood will come and get corn, peanuts… the sweet potatoes.”

It was, said Garrison, a family and community affair.

Both Garrison and Mitchell grew up in the segregated South. And while there were plenty of negatives about living in a segregated community, Mitchell said food wasn’t one of them.

“We had food all the time. Never, never was an issue of hunger, per se, because everybody had gardens, everybody had even raised bed gardens, container gardens. They had gardens inside of their windowsills in the kitchen to grow small herbs for medicinal purposes and also for seasonings and things of that nature.”

That knowledge of food and its healing properties was knowledge passed from people who owned farms in the country to their friends and relatives in the city.

“So we would go out either down to Wakulla or Crawfordville, or down to Bradfordville and Chaires. And we would go and learn how to do all the things we brought back to Smokey Hollow,” said Mitchell amid the placidness of the fruit trees, flower beds, and vegetable rows that unfold over iGrow’s land in the heart of a food desert.

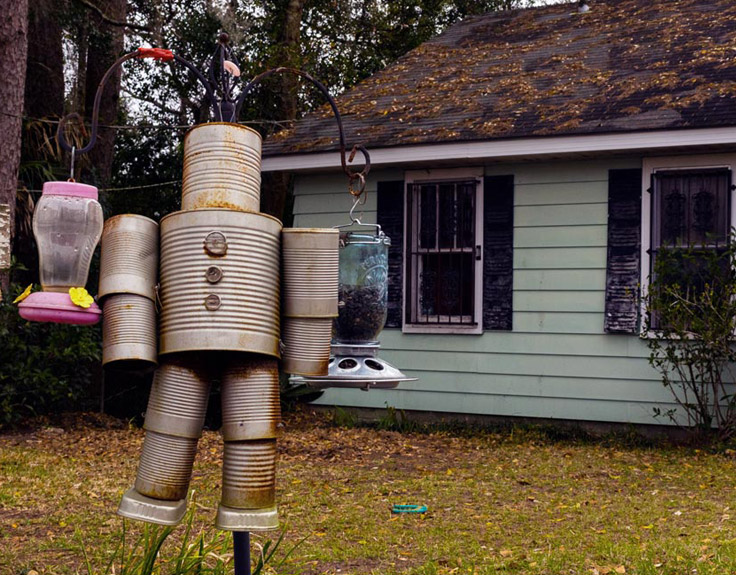

Yet, this plot of land was not always a garden. It has a history, as does the neighborhood it occupies. And folks like Mitchell have managed to transform a negative space into a positive one that’s again a step closer to the Tallahassee of Mitchell’s youth: a Tallahassee whose lands once fed both the body and the soul.

Part II: Remembering When

“Everybody had a garden,” said Ann Roberts, sitting in her modest Frenchtown home, recounting the past. “My Aunt Edie, right behind me, had a garden. When my mother was a child, they had a big garden in the back. Plus, they owned the land across the street where the pear orchard was. So they had vegetables and gardens over there,” she said, gesturing.

in this episode: featured song

- Blyke_Love, "Juneteenth Everyday"

- Blyke_Love on Instagram

Ann Roberts is an author and historian who grew up in Frenchtown and still lives there. “And people prided themselves on the gardens. How neat the rows were. How colorful it was. The various colors. Tomatoes. They were different kinds of tomatoes. The peas would run up the fence. Everybody's little plot of land was fenced off. Yeah. We had little wire fences in front and in the back here. Somebody would come and say, ‘Well, this sure is pretty,’ and I'd be wondering, “Pretty? They’re talking about a garden.’”

Beginning in the late 1960s, the Frenchtown Roberts knew began to change in a way Roberts now has mixed feelings about.

“In the very late 50s and in the 60s, there was no equality. Even though folk like to say separate but equal, it was no equality. We didn't know how well off we were living separately,” she said. “Sometimes I wish it had continued.”

Roberts is not saying that segregation was good—it wasn’t. But what it did, she said, is kept Black neighbors banded together through necessity. And what happened when it was no longer necessary?

“Times changed. People were earning more money. Goods were more accessible. And they became desegregated. So, slowly, people began to leave the areas. The areas like Frenchtown,” said Roberts.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended legal segregation. People were no longer relegated to areas of the city designated as Black-only or white-only. Roberts watched as her neighbors started to move away from their all-Black enclave.

additional content: featured blog post

- In their words: Black legacy communities in North Florida

More on growing food in Black legacy communities on the WFSU Ecology Blog.

“We had people who were educators at both the universities. We had high school principals. We had a slew of teachers. So once the area became desegregated, we had folk who moved out. But after the people came into the area with the drugs in the late sixties, everybody who wanted to get out and could get out, they did so. And a few of us are still here. I think I'm the only one who lives in the same house they were born in.”

Families left. Roberts stayed. And she watched her neighborhood begin to degrade. What was also left to go fallow where the home gardens Roberts loved, and her neighbors took pride in. As the gardens dwindled, so did Black-owned grocery stores.

“When the integration started, we felt free to go into the stores downtown. To A&P, the Winn-Dixie. We could go there much more freely. You didn't go to those stores because you were uncomfortable in them. But once the area became desegregated, you could go and feel much better.

And they had a much larger array of goods than the small corner stores here. You could even go down and get your coffee from A&P, have it ground. And my mother declared it was some of the best coffee around.”

Around the same time Frenchtown began to degrade, the residents of Smokey Hollow were forced from their homes. The two Black enclaves were less than two miles apart. The state of Florida seized Smokey Hollow land through eminent domain, creating a complex of government buildings around Florida’s historic capitol. Mitchell said many of those residents had few choices but to move into government-subsidized housing in South City or live with friends and family elsewhere.

“In the late sixties and early seventies, people were just displaced. And when you go to other people's houses and live with other folk, you don't have the same type of opportunities to grow food, they don't have the same type of values,” she said. “In public housing, they don't necessarily want you to bring any other people with you. And all you can bring is your nuclear family. You know, mom and dad and the children. But your cousins and aunties and grandmamas and all those you couldn’t bring them. And it was just hard.”

Black land loss wasn’t limited to cities. Those Black-owned farms in the country, where Mitchell's family learned about growing food? They slowly faded away as well. With devastating consequences.

Part III: Black Land Loss and Shrinking Black Wealth

According to a recent study from the University of Massachusetts, Black farmers lost $326 billion worth of acreage during the last century. For perspective, in 1900, Black farmers owned 14% of agricultural land. Today, that figure is down to on half of one percent.

“In a capitalistic society, land is extremely valuable. It's critical to generational wealth transfer,” said Dr. Sandra Thompson, a researcher at Florida A&M University. Thompson's work centers on the lives and experiences of people in and from Florida’s Black communities with long-established agricultural roots.

By the early 20th century, formerly enslaved people were looking to land to start building wealth and secure their economic and social futures.

“By 1910, formerly enslaved people had amassed over 15 million acres of land. It was based on buying a little bit at a time, maybe some given a little bit at a time,” said Thompson.

As of the 2017 USDA census of agricultural lands, the figure drops to 4.5 million acres.

Losing ownership of land was a significant economic loss. But that land was also part of communities—communities that supported and protected their members through tough times, from slavery, and through segregation. Thompson calls those communities, ‘Legacy Communities,’ ones started on plantations pre-emancipation. Some were started right after emancipation. But in both instances they are still viable, living communities.

Thompson has identified dozens of these communities in a five-county stretch of the Florida panhandle, from Madison to Jackson County. These are places like Chaires and Bradfordville. Places where development is increasing, people are moving, and many of those new residents have no idea of the history. Thompson grew up in the Legacy Community of Barrow Hill in northeast Leon County.

“One of the things is that in order to survive the conditions of slavery, you had to organize yourself in a way that you could take care of yourself, your family, and those you love,” she said.

additional content: featured research

- North Star Legacy Communities: A Florida Treasure

Learn more about Sandra Thompson's research with Florida State University's Department of Urban & Regional Planning.

This meant that families looked after each other, even after emancipation. One way was through the food they grew on the land they owned.

“My grandfather died in 1958, so we had, I think probably about initially 13 acres and then three were given to people or sold. My grandmother couldn't manage that land. So she would let a gentleman from Rock Hill, the legacy community to the north of us, farm on the land at no cost. And he grew peas and corn and all different kinds of vegetables. And that was the way of sharing and bartering in the sense that you've got all this land you can farm at no cost, but it helped manage the land, keep it so it didn't grow up. And you get to benefit from some of the vegetables that are grown,” said Thompson.

Not all of these communities have made it into the 21st century. For many, all that’s left are the cemeteries. Some, like Smokey Hollow, were lost to eminent domain. But many have been eroded due to the loss of individual parcels that have been carved up and sold off to developers, thus erasing them from history.

What’s responsible for the erasure? Mostly, heirs property laws.

“So what happened a lot of the time is, say your grandmother or grandfather had actually purchased the property. A lot of the time, it could have been property they were enslaved on,” said Billie Ventimiglia, Senior Planner at the Barnebey Planning Lab, and former project manager for the North Star Legacy Communities initiative in Jackson County.

“If me and say Ashton, Khloe, and Howard were siblings and my parents or my grandmother died and they passed it on to us, we might not have had a formalized will. So the way that happens is now we're kind of all joint property owners. If we don't agree on what to do to the property, be that to create a trust or to sell or keep it, one of us could go to court and the judge could then decide all four of us have to sell if Howard wants to sell. So that's how we ended up losing a lot of that property that was owned by Black people.”

While a better understanding of the law could prevent further loss of Black land, it can’t bring back what’s already gone. Both in the city and in the country, people of color have lost communities, or seen them radically altered. And many people have lost touch with their agricultural roots. At the same time Black land loss was being felt in the 20th century, Black communities began to experience a rise in health problems such as (Type 2) diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity—all diseases that can be food related.

It’s connecting with the earth. It is getting back to your roots as a human being.

PART IV: Returning to the Roots

In 2012, a group of community leaders and youth volunteers tried to re-establish their connection to the land in a new form: the community garden.

Sundiata El oversees the Frenchtown Urban Farm and Compost Community. It backs up to the iGrow garden which is a street over.

“We also compost, as you see here, surrounded by compost material here. And it's just that, it's just an urban market garden is what we would call it,” he said, giving a tour of the space.

Crops at the Urban farm are grown in rows, like on a commercial farm. From Dunn Street, you can see piles of earth and vegetation in various states of breakdown.

“Anything that we grow, we try to bring those commodities to the general public. So, we'll set up at a Frenchtown Farmer's Market. We'll also sell through an online market, Red Hills, which you're familiar with. And we focus on composting as our primary business model. And then from there, we grow food, and we recycle that food into the community and the scraps come back to us to reintegrate back into the compost program. So, it's kind of like a closed loop system that we've been able to create,” El explains.

El doesn’t come from a family of farmers, but indirectly his family provided his connection to the soil.

“I come from a family of entrepreneurs,” he said “And the reason why I'm actually in Florida is because my father, 40 something-odd years ago, came to Tallahassee with his brother-in-law to start a worm business. So, they came to Tallahassee to grow and cultivate red wiggler worms for bait.”

Years later, El would end up working with those same worms, but in a different way.

“Within agriculture,” he said.

“It’s connecting with the earth. It is getting back to your roots as a human being.”

The Urban farm’s shared space with iGrow isn’t by chance. Both have their roots in the same mission: return a part of Frenchtown to its roots and combat the health problems that came when fresh food was no longer easily available.

According to the National Institutes of Health, Black adults are nearly twice as likely as white adults to develop Type 2 diabetes, and that, “this racial disparity has been rising over the last 30 years.” It’s a disparity driven by obesity rates.

But the problem is far more complicated than just access to healthier choices. In a 2018 interview, El noted most of his customers are not Black—despite both iGrow and the Urban Farm being in the heart of a predominantly Black neighborhood.

“The majority of the people who buy from this online venue are usually Caucasian, upper high-middle class and on the north side of town. We’re dealing with people who are educated in terms of why these foods are important,” El said at the time.

That doesn’t mean Black communities don’t understand the importance of fresh, organic foods. They do. The issue is one of race and class. Conventionally produced food is cheaper because agriculture today is largely subsidized by federal and state governments. Organic, locally grown food is not. And due to Black land loss, it’s rare to find viable, small organic farms owned by African Americans who sell their produce to Black communities.

A safe space

“I come and sit on a bench until daybreak because I know it's a safe place. But one thing about this piece of peace, it’s a safe place,” said Eric Prather, a Frenchtown resident who finds respite in the gardens.

Prather is homeless, and the garden, he said, provides him with grounding. He also recalls what the lots that now house the gardens were before iGrow and the Urban Farm moved in.

“I had two friends who died in this field here, before the garden. People have got robbed in this field before the garden. And I’ve been in this community all my life. It changed a lot of people's direction, you know, from evil things, you know. Let's go to the field. It's not the field anymore, it's the garden. A place of peace. This garden has done a lot for this community. You know, it's not just a garden where they grow things. It’s a place of peace where some of us, you know, who are addicts, or homeless, we could come here and think. Smell fresh flowers, vegetables, and just sit down you know, just think by ourselves, you know, just have peace. Get away from the world. Inside the garden, it’s more than a garden.”

The neighborhood around the farm and garden is much like longtime resident Ann Roberts described it earlier, with a few empty lots and abandoned homes. To some, it’s a sign of decline, but Roberts feels optimistic about the future of her neighborhood:

“This is an old area,” she said. “We live next to people who had been here forever. So, it has been a great place to live considering some of the things that have occurred here. And we are trying to improve it to bring it back to a viable single-family area.

FAMU’s Thompson said it all begins by helping people get back to their roots and by “bringing recognition and elevating this history and talking about it. We are then able to reintroduce, to motivate people to see what it could be like, what it was. How can we put all of those practices into play today?”

It’s an ongoing issue that is not so Black and white.