The Father of Refrigeration

Most of us know Dr. John Gorrie as the father of refrigeration. But there is surprisingly little other information about him out in the public sphere. And some of what is thought to be known is contradictory. According to the book The Fever Man, Gorrie claimed to have been born to the mistress of a Spanish royal on the Isle of Nevis, in the Caribbean. But 1840 Franklin County Census records list Charleston, South Carolina as his birthplace in 1804, and that he was of Scotts-Irish descent. The Statuary Hall website in the United States Capitol lists his birth date as 1802, while his gravestone is etched with an 1803 birth date. He grew up in Columbia, South Carolina, and attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Western District of the State of New York beginning in 1825. He completed a three-year curriculum in 2 years and his intellect was highly admired by his teachers. By 1828 he had returned to South Carolina and started a medical practice in Abbeville.

Dr. Gorrie Comes to Town

1833 was the year Dr. Gorrie arrived in Apalachicola. It’s unknown if this was by design, or if he’d just run out of river. He had traveled south by riverboat from Columbus, Georgia, down the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers, stopping at towns along the way. In 1833 Apalachicola was an outpost of world commerce in the middle of an untamed wilderness. Cotton coming downriver, out to the northeast, and all of Europe. Finished goods came in from Europe and the Caribbean, then headed upriver to the interior. Ownership of the land the town was situated on was still in a dispute related to the Forbes Purchase and would not be decided by the Supreme Court for another two years. Apalachicola had antebellum gentility, coexisting with a dirty, bug-infested, rough and swampy waterfront.

Mrs. Gorrie and the Kids

In May of 1838, the good doctor married Caroline (Myrick) Beman, the new owner of the Florida Hotel in Apalachicola. She was a widow from Georgia, but she had Myrick family relatives in Apalachicola and her father had large agricultural landholdings inland. The Florida Hotel stood approximately where the Fort Coombs Armory building sits today. Together, the Gorries had two children, a son, also named John, and a daughter, Sarah. John, Jr. later fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War and then served as a state senator from Marianna from 1865-66. He died in a carriage accident on his way to Tallahassee for a legislative session.

Yellow Fever is the Father of Invention

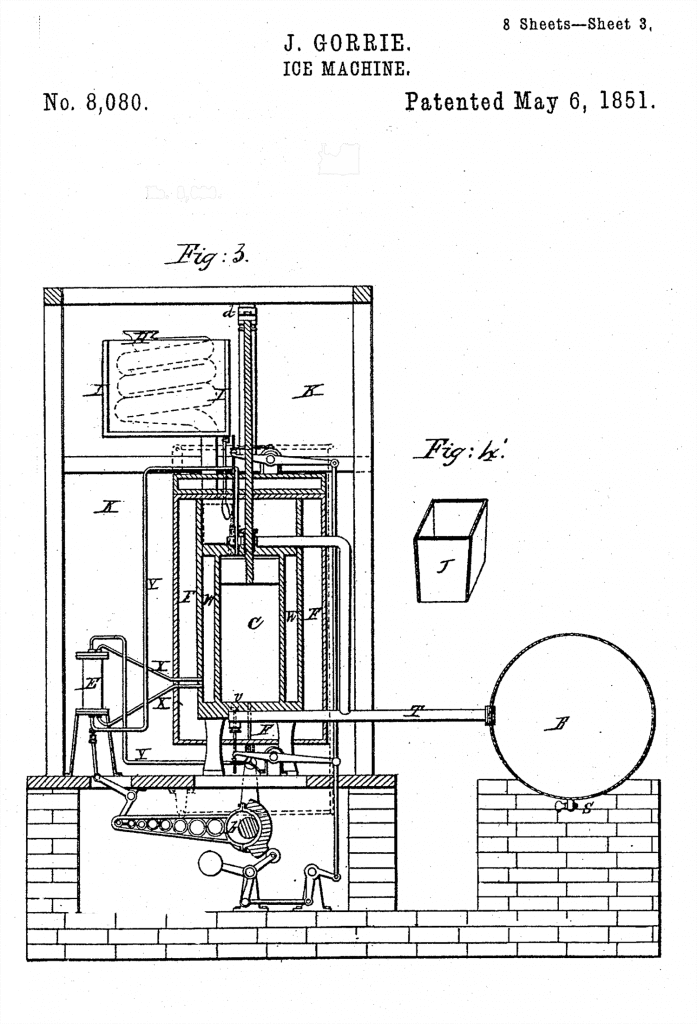

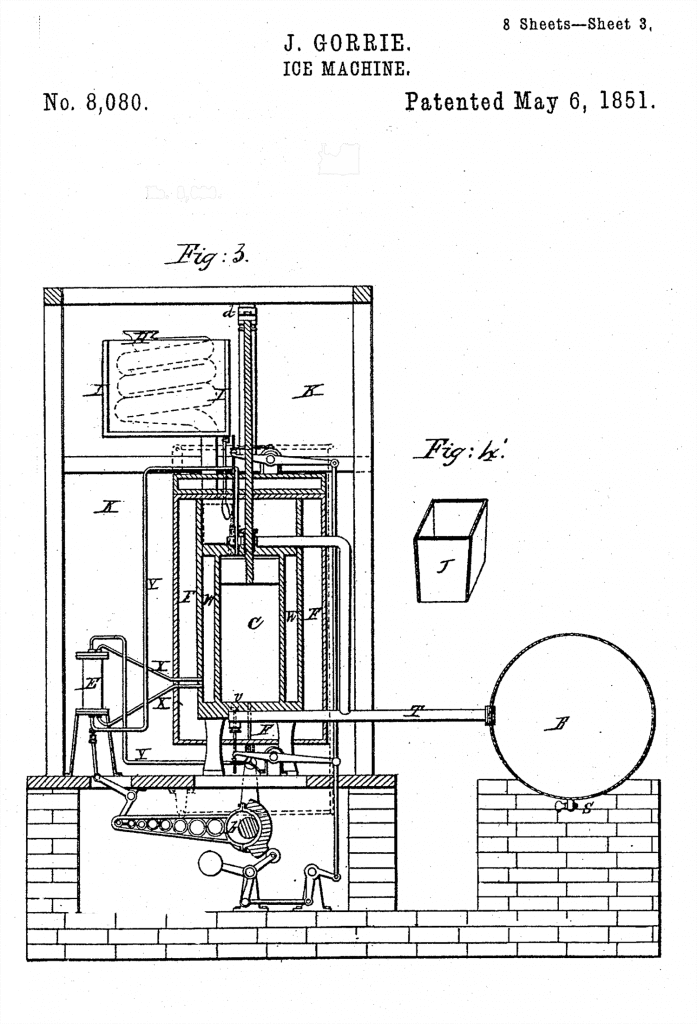

Yellow fever outbreaks in the summer months set Gorrie on his path to inventing artificial refrigeration. The medical consensus at the time associated the saffron scourge with summer heat, not the disease-carrying mosquito. Profit was not Gorrie’s motivation, he sought to ease the suffering of his patients. After years of experimentation, Gorrie was awarded patent no. 8080 in 1851 for his Improved Process For The Artificial Production Of Ice. Unfortunately for Gorrie and the rest of the world, the northern ice syndicate, which controlled the ice trade, didn’t share his philanthropic enthusiasm. They saw his invention as a threat to their money-making cartel and set out to discredit Dr. Gorrie, attacking him in the press. It would take a Civil War and naval blockade preventing the delivery of northern ice to bring artificial ice production to the south. Once there, the frozen genie was out of the bottle.

Death of the Doctor

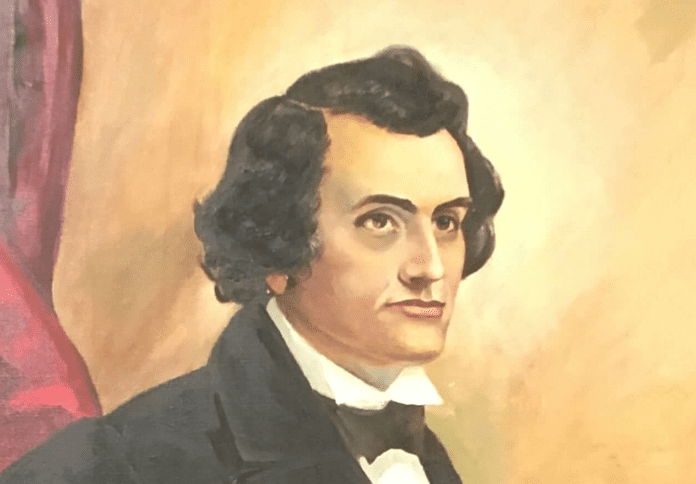

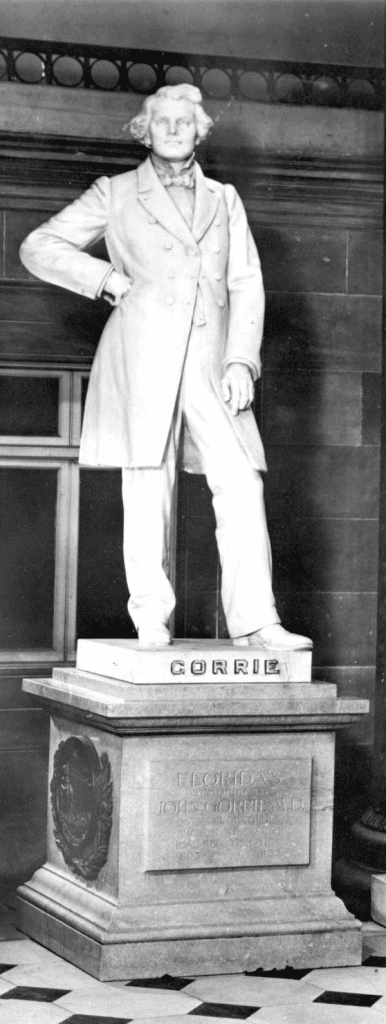

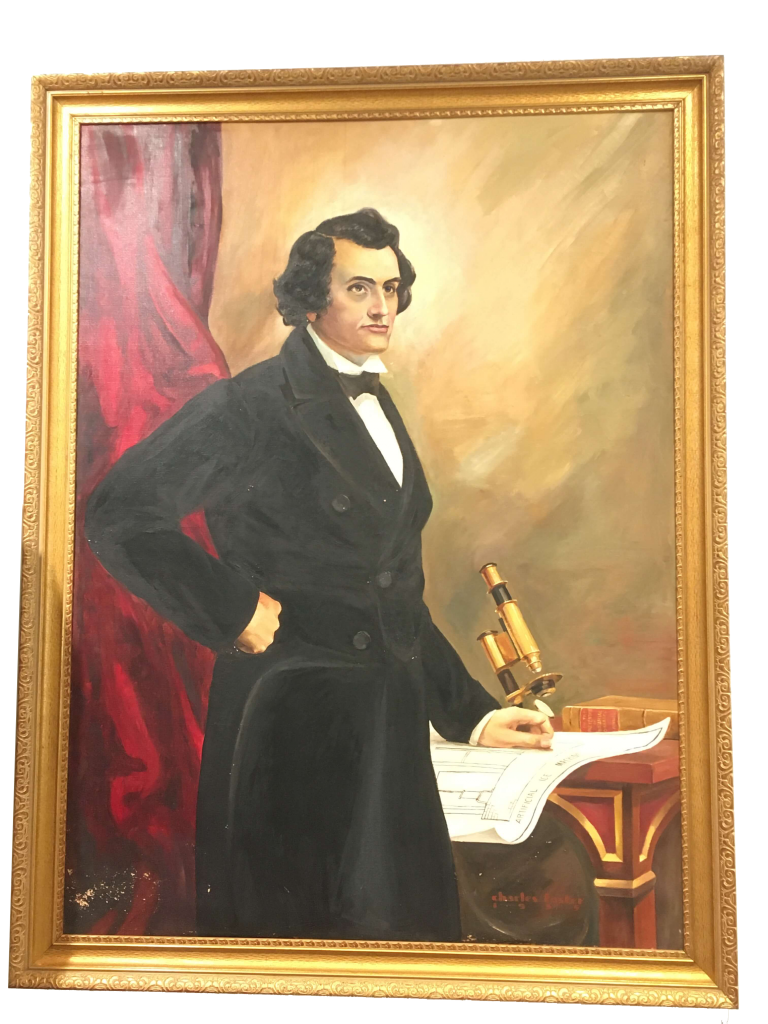

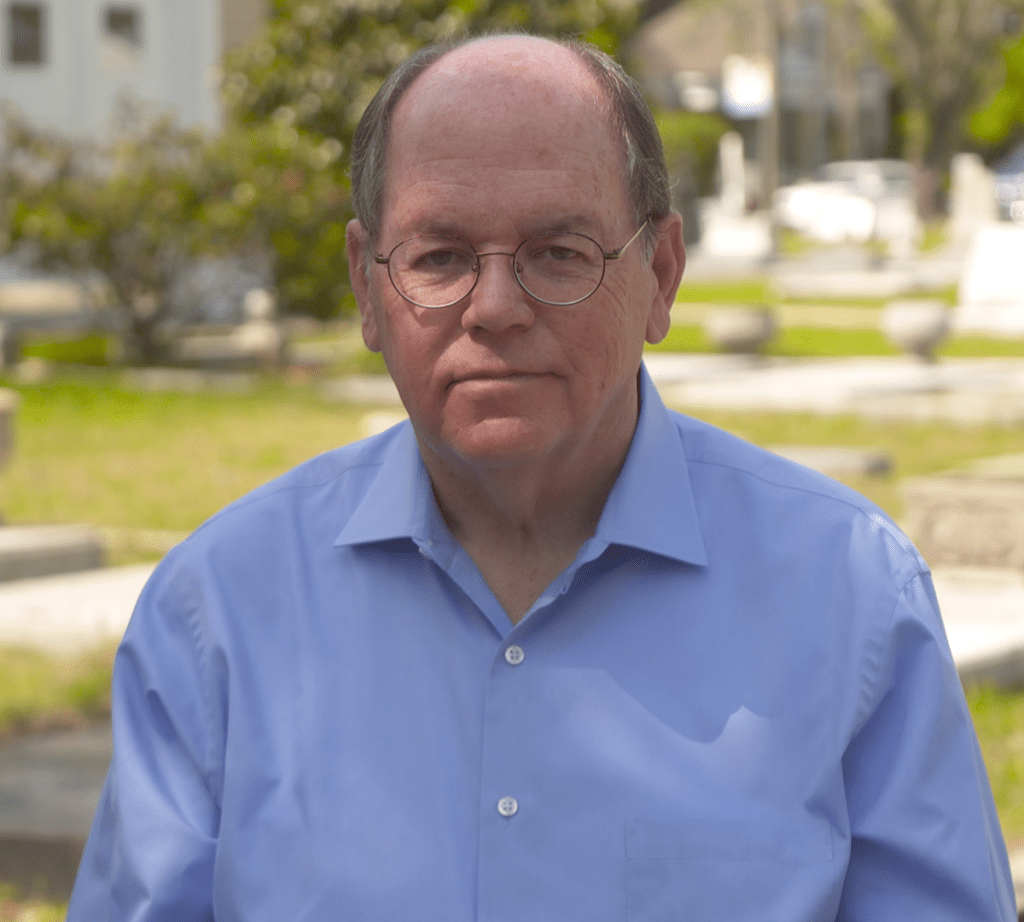

Dr. John Gorrie died on June 29, 1855. He had just returned from New Orleans when he fell ill and the cause of his death is unknown. It is often stated that he died a broken and defeated man because he couldn’t get the world to take his ice-making machine seriously. But he was far from broke. He and Caroline had landholdings and they had prospered during their time together. A monument to Dr. John Gorrie was erected in 1899, in front of the Episcopal church in Apalachicola. It was sponsored by the Southern Ice Exchange; they had profited from his invention and wanted to express their gratitude for his work. The only widely known image of Dr. Gorrie is a portrait painted by artist Charles Foster, commissioned by his granddaughter, long after his death. Reportedly, the artist was working from a daguerreotype taken of the doctor.

But wait! There’s more!

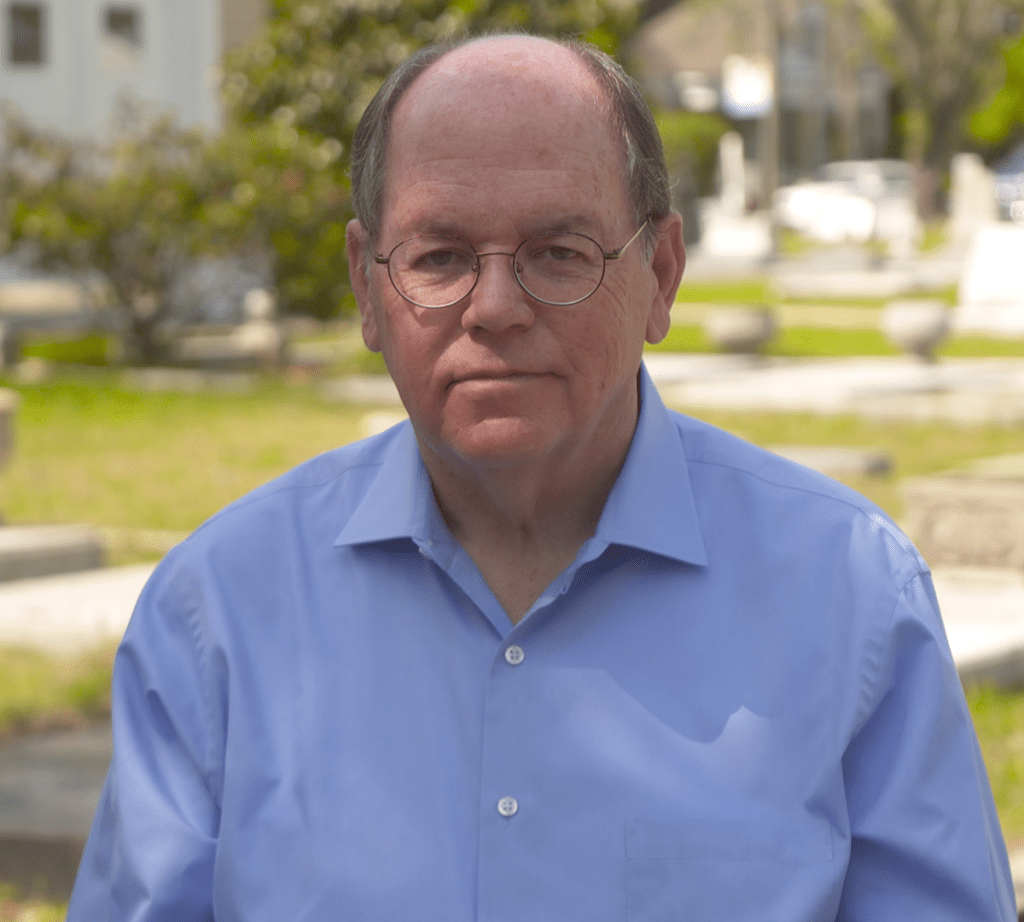

Mike Plummer is a content producer and editor for television at WFSU Public Media. He spent 25 years in commercial television as an art director, commercial director, promotion manager, station manager and creative services director before coming to WFSU in 2008. Mike likes to find the “unusual” or “out of the ordinary” stories in our Local Routes. He says the best part of his job is getting to know people he would otherwise probably not get a chance to meet. Mike is widowed, has a rescue dog named Dexter, and is constantly at war with the vines growing in his backyard.