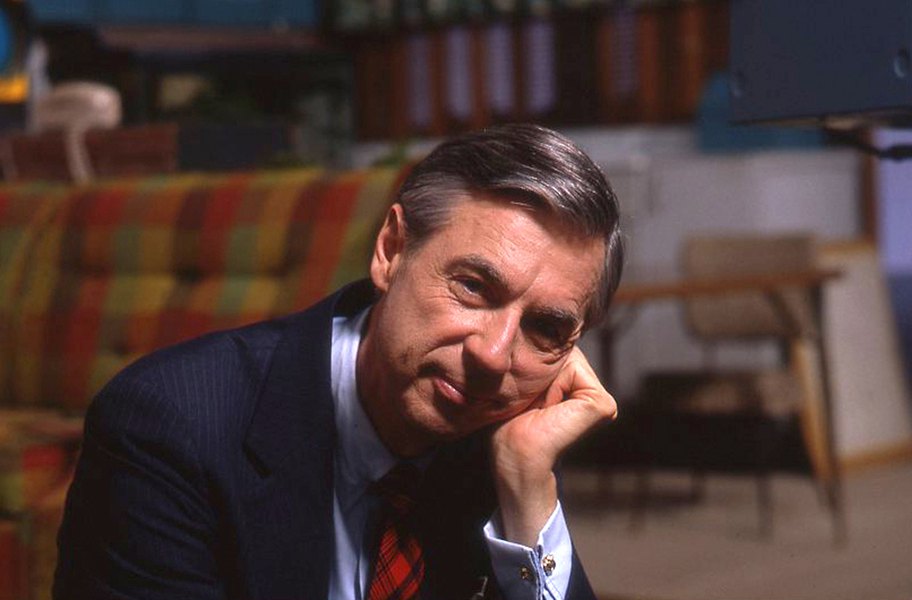

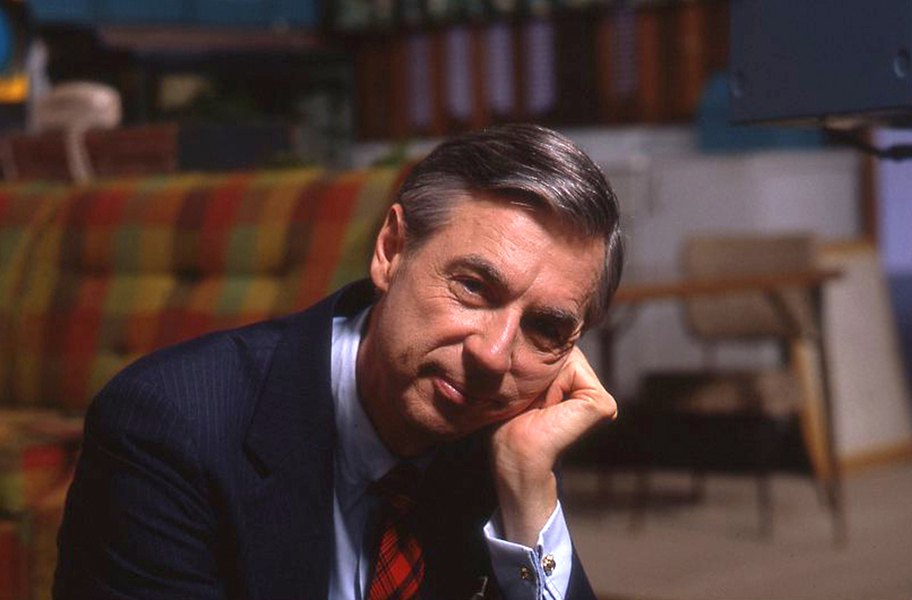

It’s 1993. Fred Rogers enters a noisy hotel lobby, taking pictures of the people who have come to meet him. You realize that you have lowered the volume of your voice.

I look down at my son, Matthew, who had turned 6 on the day before Halloween. Normally ebullient and outgoing, Matthew is rigid with tension, and I notice that his upper lip is quivering. Rogers smiles and shakes Matthew’s hand and, before long, interrupts his conversation with the two adults and talks directly to Matthew.

Noticing that Matthew has pulled a book about rocks out of his little backpack, Mister Rogers tells the boy that he loves rocks, too, and that he owns a lapidary machine, which he keeps in an outbuilding on his property because of its constant whirring.

Matthew’s eyes widen. His own birthday present was a lapidary machine, which right now is in our house rolling and polishing some of the billion or so rocks that he has collected.

Rogers asks Matthew to show him his book, and now they whisper the secrets of stone.

I wonder: How many thousands of other children have Mister Rogers connected with in this way? For most people, such continual expectation of attentiveness would wear thin.

He turns to the other reporters in the room and other guests. One asks him what inspired him to pursue television as a career. He recalls, “It was Easter, 1951, and I saw people on television throwing pies at each other, and I thought, I want to work in that medium.” Among his career’s most famous moments was when he gently explained to America’s children what the word assassination meant after Bobby Kennedy was killed in 1968.

To his satirists, his cardigan sweater and soft voice are more bizarre than any clown wig or polka-dot suit; he is that rarest of television creatures: real.

I ask how he feels about the frequent impersonations by comedians, especially Eddie Murphy’s scalding sendup on Saturday Night Live, “Mister Robinson’s Neighborhood.” He says, in effect, that he does not take such satire personally. It does not hurt him. Not long afterward, he met Murphy, who burst out of his office, arms spread, grinning, and said, “It’s the real Mister Rogers!” Mister Rogers spread his arms and said, “It’s the real Mister Robinson!”

Other impersonations have been…harsher. Legal action was used to stop the Ku Klux Klan from passing out slips of paper in schoolyards in a Midwestern town encouraging children to call a telephone number; a voice sounding like Mister Rogers would answer with racial and religious hate messages.

He is deeply troubled by the violence and quickening pace of children’s entertainment. He says he does not watch much television himself. When children go to the refrigerator, he says, they assume that what the adults in the family have put in it is not poisonous. Children think of television in the same way.

Despite his anger at TV violence, he stops short of any political statement, any endorsement of proposed legislation to curb the violence, but he does not reject the idea. “There is so much we can do that has nothing to do with censorship. I know many people in the industry with basically good motives. They’re going to have to limit themselves, even if it means not making quite so many millions of dollars.” In 1993, the internet and smartphones are yet to become issues of concern.

He pauses, then says:

“Isn’t it amazing how much human beings are able to take? I wonder what the breaking point is. But I always look for the faithful remnant. You think that everything is lost and nobody believes in anything that is healthy anymore, and all of a sudden you find this faithful remnant of hope. It’s like my mother said, always look for the helpers. At the edge of any disaster, you will find them.”

As the other reporters leave to meet their deadlines, and the crowd thins out, Rogers turns and walks back to Matthew and me. His smile has nearly disappeared. He leaned close and said he wanted to say something more about the satirists who made fun of him. He said his earlier answer had not been fully honest. He said some of the impersonations, including Eddie Murphy’s, did hurt him at first. But over time he became convinced that Murphy’s was done with affection.

He had come to accept the seeming accuracy of some of the impersonations. “I think if I were playing a part, that would really bother me. I don’t play the part of Mister Rogers. I am Mister Rogers.” And he had realized that, regardless of how others may respond, one of the most important gifts a person can give “is the gift of your honest self.”

Remembering that Rogers is an ordained minister (and this explains something about his essential nature; he is more spiritual friend than an activist), I mention to him that Matthew had asked me a theological question the other day, for which I did not have a good answer.

“What was it?” Rogers asks.

“Matthew said, `Dad, I’ve been wondering about something. Is God married to Mother Nature, or are they just good friends?’ ”

I had involuntarily laughed when my son said this the first time. Like most parents, I don’t always take my children’s pronouncements as seriously as I should, and my sometimes my reactions understandably anger them.

Mister Rogers does not laugh. “That’s a very interesting question, Matthew.” He thinks about it for a long moment. “Your mom and your dad are married and they’ve had two fine boys, and they’re mighty important to those two boys, and I think that’s one way we get to know what God and Nature are like, by having a mom and a dad who love us.” Maybe the statement isn’t entirely inclusive (what about single parents?) but the answer seems to work for Matthew, who nods.

Later, as everyone stands to leave, Mister Rogers walks over and sits next to my son. “Will you let me know, as time goes by, what answer you find to your question?” he asks gently. He is reopening the door to the question, encouraging Matthew to have the last word.

That is what a real friend does.

____________________

Postscript: In 2002, a year before Fred Rogers died, Matthew, then a teenager, sat down at the computer and wrote him a letter sharing his private thoughts about the answer he had found for himself. Mister Rogers sent a note in return, along with a photo of the two of them. He said that he appreciated Matthew’s “kind words about the conversation we had about your question of God and Mother Nature.” He asked him to give his father his personal regards, and added, “Matthew, you’re such a thoughtful young man. I wish you well in all that lies ahead.”

____________________

Richard Louv is co-founder and Chairman Emeritus of the Children & Nature Network and the author of eight books, including Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder and The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age (Algonquin). His books have been translated into 12 languages and published in 17 countries and helped launch the international movement to connect children and their families to nature. He is the recipient of the 2008 Audubon Medal. He has served as an adviser to the Ford Foundation’s Leadership for a Changing World award program, is a member of the Citistates Group, serves on the editorial board of Ecopsychology, and appears often on national radio and television programs, including The Today Show, CBS Evening News, and NPR’s Fresh Air, and travels frequently to address international gatherings. In 2010, he delivered the plenary keynote at the national conference of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and in 2012 was the keynote speaker at the first White House Summit on Environmental Education. He has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Times of London, Orion, Outside, and other newspapers and magazines, and was a columnist for The San Diego Union-Tribune and Parents magazine.